The warning signs in consumer credit data

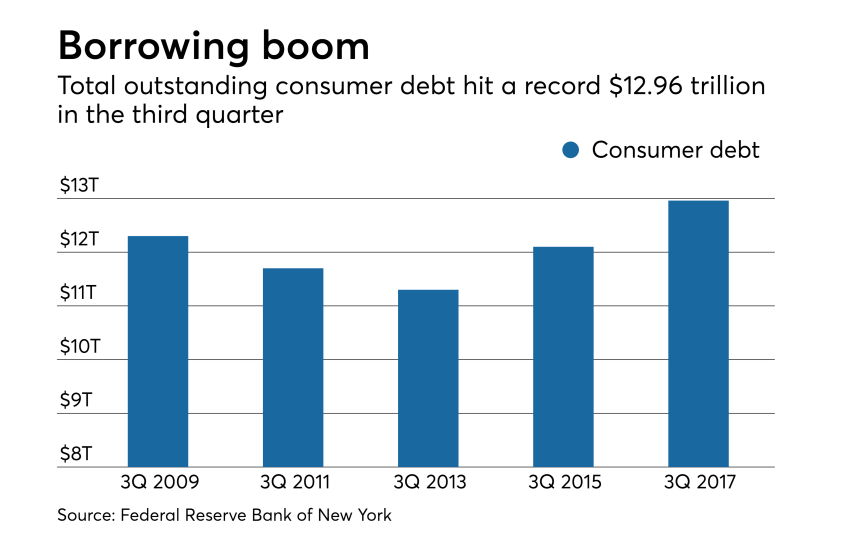

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York said in September that consumer debt hit a record $12.96 trillion in the third quarter of 2017, as student and auto loan totals reached all-time highs and mortgage and credit card debt crept closer to pre-financial-crisis levels.

It’s an eye-popping figure to be sure, but

The New York Fed has noted that its data is not adjusted for inflation, and the cost of goods and services has risen by more than 10% since 2008, the last time total consumer debt neared the $13 trillion mark. Moreover, the U.S. population has increased by about 7% during that span, which means that, on a per capita basis, consumer debt is actually lower than it was a decade ago.

Another sign that households are managing their debt reasonably well: Foreclosures hit a new historical low in the third quarter, according to the New York Fed.

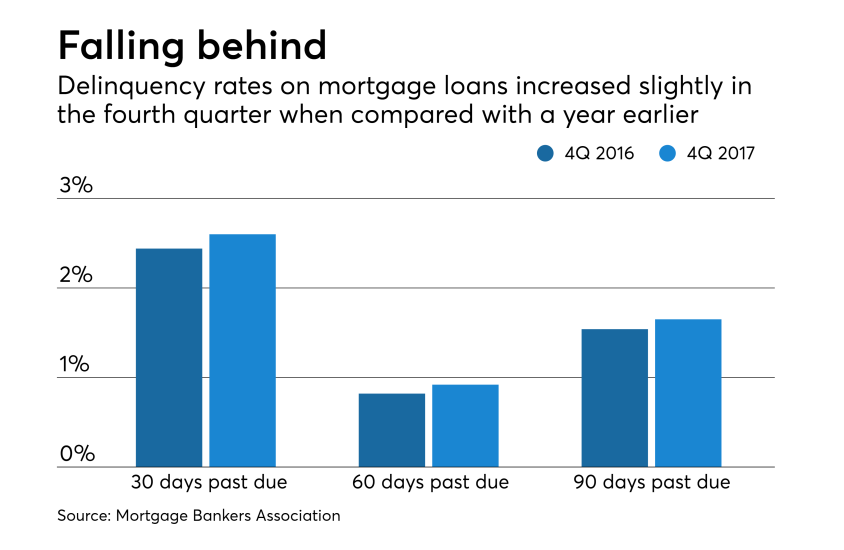

Still, there are reasons to be concerned about rising debt levels. The personal savings rate hit a 12-year low at the end of 2017, which means that many households likely do not have enough of a financial cushion to weather sudden economic shocks, like a major medical bill or a busted refrigerator. Delinquencies on all types of consumer loans, while nowhere near 2009 and 2010 levels, have started to tick up in recent quarters. Factor in slow wage growth and high housing costs in many urban markets and it is not hard to imagine many households struggling to keep pace with their monthly bills.

It’s too soon to say what this all means for banks, but not too soon point out the warning signs. Here they are.

Sinking savings rate

This decline in personal savings can be interpreted in a number of ways. On one hand, it suggests that a sizable number of households are

Then again, the decline could be a result of more consumers tapping savings to buy homes, cars or other big-ticket items, and all that is a sign of growing confidence in the U.S. economy, according to Dr. Dan Geller, a San Francisco-based economist. Geller uses a metric called the “Money Anxiety Index” to gauge consumer confidence, and he said Friday that, even after Wall Street's wild week, the index is at its lowest level since before the Great Recession. The February index stood at 51.4%. The 50-year average is 70.7%, and during the the height of the recession it peaked at 100.4%, Geller said.

“Increased financial confidence…has fostered a condition where individuals are more confident to decrease the amount they save, or even utilize part of their existing savings, to help fund their consumption,” Geller wrote in a report released Friday. “As long as the economic fundamentals, such as employment, inflation and personal income remain stable, the level of money anxiety will remain low, and people will continue to spend money despite this temporary volatility in the equity market.”

An uptick in delinquencies

Now the good news: While consumer loan delinquencies rates may be trending up, they are coming off historic lows and are nowhere close to financial-crisis levels. At the height of the crisis, some 11% of credit card loans, 4% of car loans and 8% of personal loans were seriously delinquent. Home equity loans delinquencies, which peaked at 5.03% in late 2009, are now below 1%.

This slight weakening in credit quality has caused some banks to boost their loss reserves, tighten lending standards and even scale back their lending in some sectors. But, overall, lenders remain bullish on consumers, as evidenced by the fact that they continue to write new loans. Total consumer loans issued by banks and credit unions have increased in every quarter since mid-2013.

The high cost of housing

While the housing market is far healthier than it was a decade ago, a dearth of inventory has pushed the cost of owning or renting a home to record highs in many metropolitan markets.

A study released last year by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University found that roughly 11 million rental households and close to 8 million homeowners were “severely cost-burdened,” meaning that they spend at least 50% of their monthly income on housing. The general rule of thumb is that housing costs, including utilities, should consume no more than 28% to 30% of household income.

Many millions more households were deemed to be “moderately cost-burdened,” meaning they spend between 30% and 50% of monthly income on housing, according to the report.

That data could partly explain why mortgage delinquencies, while still low by historic standards, are trending up a bit. In a report released Friday, the Mortgage Bankers Association said that 30-, 60- and 90-day delinquencies all increased in the fourth quarter when compared with a year earlier (see chart).

A recent uptick in construction has eased the burden on households somewhat, but most housing economists say that the demand for housing still far outstrips the supply, particularly at the lower end of the market.

The student debt threat

Total outstanding student debt stands at about $1.4 trillion, up from about $960 billion at the end of 2012. Alarmingly, more than 11% of total student loans are seriously delinquent. In no other consumer loan category are delinquency rates anywhere near those levels.

So what are the ramifications of all this? For the majority of these borrowers, the investments in education will pay off in the long run, but in the short term many are likely to delay buying homes or cars until they can whittle down their debt. Those borrowers who end up defaulting on their loans, meanwhile, will suffer serious damage to their credit records that could take years to repair.

This rapid rise in student debt threatens to hamstring not just borrowers, but also their parents, according to LendEDU, an online marketplace for student loan refinancing. LendEDU recently polled 850 parents who have co-signed loans for their children, and 62% said that they believe their decision to co-sign has negatively affected their credit score, 47% said it is jeopardizing their retirement and 40% said it has hurt their ability to qualify for a mortgage or other type of loan.

Still, despite these risks, most parents don’t regret their decision to co-sign their childrens' loans. Asked if they would do so again, 66% said “yes.”