Kovacevich's strategy, which continued under recently departed CEO John Stumpf, hinged on selling more products to the bank's existing customers. Branches were stores, since stores are where consumers buy products.

The firm's sales culture has drawn sharp criticism in the wake of the revelation that the firm's employees opened as many as 2 million fraudulent customer accounts between 2011 and 2015. In response to the scandal, Wells announced that it was eliminating sales goals altogether. Here is a look back at some key milestones in the development and unraveling of the firm's once-vaunted sales culture.

Related:

It All Started at Citi

"I never heard of a retailer who didn't want customers coming to the store," Kovacevich told the New York Times many years later. "Yet you often hear bankers complain about people who waste their time, ask too many questions and get the carpet dirty."

Kovacevich was eventually passed over for the job of head of retail banking at Citi. In 1986 he left the New York bank to become chief operating officer at Norwest.

Kovacevich Joins Norwest, Develops the Blueprint

"The war we are in will be won on the field of revenue," Kovacevich told American Banker in 1995. "And the most effective way to gain revenue and profits is to cross-sell to customers."

At Norwest, Kovacevich's deputies included Stumpf, who spent time during the early 1990s consolidating banks in Texas, and Carrie Tolstedt. Tolstedt eventually became the head of community banking at Wells Fargo, retiring shortly before the recent scandal erupted.

Norwest Merges with Wells Fargo

The new company kept the Wells Fargo name, and the two predecessor firms had equal representation on the board of directors. But Kovacevich became CEO. And he was determined to bring Norwest's sales culture to the West Coast.

At the time of the merger, Norwest was selling 3.8 products per household, but the merger dragged that number down to 3.3. Three years later, the cross-sell ratio was 3.7, which was still far below what Kovacevich thought it should be. Wells established a goal of selling at least eight products to every customer.

"The cost of selling an additional product to an existing customer is only about 10% of the cost of selling that same product to a new customer," Kovacevich said in 2001. "That's why cross-selling delivers extraordinary profits."

Stumpf Takes the Reins

Prior to his appointment as CEO, Stumpf promised no "sea change" in strategy.

"We have the right vision and focus," Stumpf said. "The debate over how we get there how we create more customer loyalty, how we're more elegant and simple in our product offerings and design is ongoing."

Wells Buys Wachovia

The deal gave Wells a nationwide footprint for the first time, but it also posed a new challenge to the company's sales culture. Among the changes: Wachovia's branches were remodeled to accommodate larger sales staffs.

Related:

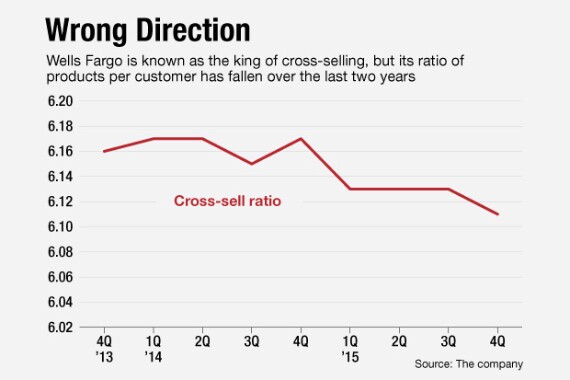

Cross-Selling Strategy Sputters

That stagnation overlapped with scrutiny of the bank's sales practices. The Los Angeles Times first reported on phony accounts at Wells in 2013. An investigation by local and federal agencies followed. Between 2011 and 2015, Wells fired some 5,300 employees in connection with the fraudulent accounts.

Related:

Stumpf Toppled Amid Scandal, Sloan Takes Over

Sloan is not forsaking cross-selling. But he has recently suggested that the company's fabled sales culture was taken too far.

"There are things that need to be fixed within our culture. There are weaknesses within it that we must change," Sloan told a gathering of Wells employees late last month.

"We had product sales goals that sometimes resulted in behaviors and practices that did not serve our customers' or our team members' interests. And we were slow to see the harm they caused."

Related: