10 who had a rough year in 2017

Equifax, the credit reporting agency whose primary responsibility is to protect consumers’ personal information, became public enemy No. 1 this year when it revealed that thieves hacked into its database and stole the personal information — birth dates, credit card data, Social Security numbers — of some 145 million consumers. As bad as the breach was, CEO Rick Smith made it significantly worse by waiting more than a month to make it public.

What happened next was predictable: Outraged lawmakers summoned Smith to Capitol Hill for a public flogging and Smith, who had been CEO of Equifax since 2005, was ultimately out of a job. By any measure, that’s a bad year.

As for Wells Fargo, while it took a number of steps to right the wrong of its phony-accounts scandal, its reputation remains severely damaged. Moreover, its current CEO, Tim Sloan — who replaced John Stumpf last year — continues to be dogged by the perception that he’s too much of a Wells Fargo insider to meaningfully change the bank’s culture. At a separate, equally hostile grilling on Capitol Hill, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat, told Sloan he “should be fired” for not reining in the bank’s abusive practices.

Also included in American Banker’s annual “10 who had a rough year” list: the founder of a high-flying fintech who was ousted for sexual misconduct; a longtime community bank CEO; the authors of a discredited research report on peer-to-peer lending; and the federal regulatory agency bankers love to hate.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

The Senate

Meanwhile, the agency has been locked in an ugly partisan battle for control of the agency since President Trump

Deputy Director

Mulvaney has also launched a temporary freeze on all rulemakings and hiring, and is likely contemplating shrinking the CFPB’s staff and budget.

Tim Sloan, CEO, Wells Fargo

For those who haven’t been keeping score, the bank has in recent months: admitted to charging

To be sure, Wells Fargo has taken a number of steps to right the wrongs of a phony-account-opening scandal that cost it some $190 million in fines and restitution and led to the ouster of Sloan’s predecessor, John Stumpf.

Nonetheless, Sloan continues to be dogged by the perception that he’s too much of a Wells Fargo insider to bring about cultural change.

Savers

The Federal Reserve in 2017 continued increasing rates at a steady pace, announcing hikes of 25-basis-point in

That may be on the verge of changing. Big companies and wealth management clients have begun negotiating more favorable rates on their deposits. With the central bank

Mike Cagney, ex-CEO, SoFi

He started Social Finance with some of his fellow Stanford Business School students in 2011. In the beginning, the company only offered student loans, but it did so in pursuit of a broad relationship with a coveted set of customers — graduates of elite universities.

That business plan gave SoFi an edge in the crowded online lending field. In 2015 the company raised $1 billion from the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, and in 2016 Cagney was named one of American Banker’s "10 who had a good year."

His fall came fast. In August 2017, a former SoFi employee alleged in a lawsuit that he had witnessed female managers being harassed, reported the misconduct, and was subsequently fired. The following month, amid additional allegations that SoFi had a culture that was hostile to women,

Banks in Puerto Rico

Three months after the Category 4 made landfall, roughly one-third of the island is still without power. Though nearly 90% of bank branches have reopened, as well as nearly 1,600 ATMs, according to a

And longer-term challenges remain. During the third quarter, banks on the island boosted their third-quarter

Additionally, outmigration is a lingering worry, as more than

One potential silver lining: The process of rebuilding damaged buildings and infrastructure could

Rusty Cloutier, ex-CEO, MidSouth Bancorp

Energy exposure — or, perhaps more accurately, a reluctance to aggressively tackle problem oil and gas loans — did him in. At the time of his removal, energy loans made up 18% of MidSouth’s overall portfolio, and nearly one-fifth of those were past due. Last year’s profit was off 64% from 2014, the year before oil prices began a prolonged swoon.

The board, led by former NFL quarterback Jake Delhomme, decided that a change in leadership was needed to address the energy exposure and raise the capital required to purge the portfolio. Cloutier still stands to gain from the change; he is among MidSouth’s biggest shareholders and would benefit if new management rights the ship and improves the company’s stock price.

Cleveland Fed researchers

The study, titled “Three Myths about Peer-to-Peer Loans,” found the sector’s customers typically end up in deeper debt and have lower credit scores than similarly situated consumers who abstain.

But as soon as the study was published,

In fact, the company that provided the data said that it did not distinguish between peer-to-peer loans, so-called fintech loans and traditional personal loans.

Just nine days after the research was published,

Rick Smith, ex-CEO, Equifax

Thieves hacked into Equifax databases during the summer and stole Social Security numbers, birth dates, addresses and credit card numbers, affecting 145 million consumers. But the breach, which could cause trouble for consumers for years, wasn't disclosed until September.

Lawmakers

Further, Smith was lambasted for

Later in September, the 57-year-old Smith

The fallout continues. The

Office of Financial Research

But instead the agency has ended up being largely quiet, releasing reports on risks that are often ignored.

This year, however, it got noticed — just not for the right reasons. OFR Director Richard Berner abruptly announced his departure last month despite having a year left on his term. The Government Accountability Office, meanwhile,

The Treasury Department, which oversees the OFR, has pledged to slash its budget and staff significantly in 2018 and there are doubts that it can continue to operate as an independent arm.

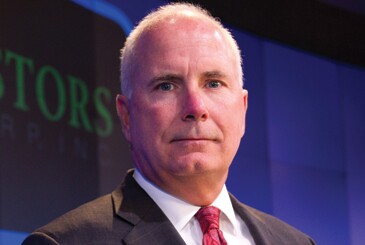

Kevin Cummings, President and CEO, Investors Bancorp

Earlier this month, the $25 billion-asset Investors announced it would shutter six branches and trim approximately 5% of its workforce — about 100 people — to reduce expenses by up to $12 million. Costs have climbed as the bank, led by President and CEO Kevin Cummings, works to meet the terms of an informal agreement with regulators that require it to beef up its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act strengthen its defenses against money laundering.

Those concerns had already forced Cummings to

The $154 million deal, which would have been its fifth acquisition since 2012, would have marked Investors’ first big move into the Philadelphia market.