Legacy card issuers are facing a huge problem that threatens their relevance. Most of them are trying to launch a spaceship with a steam engine, and many of the solutions to that quandary are expensive, risky — and temporary.

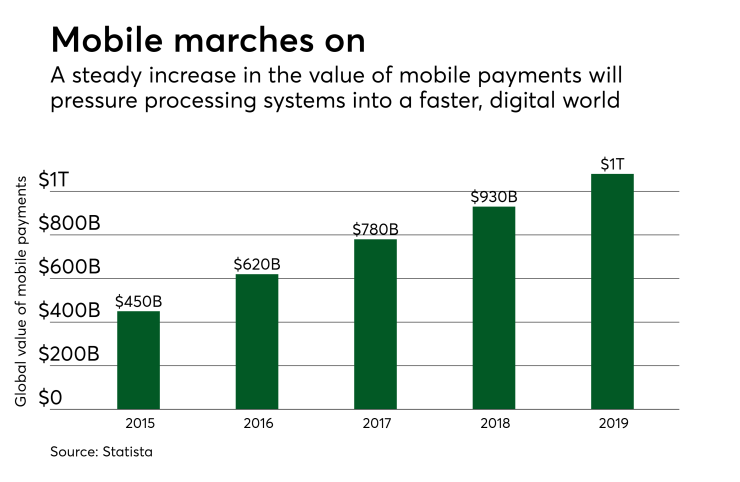

The barrage of faster payments, mobile payments, wearable payments, cross-border payments and open banking not only require a quick and accurate strategic response, but are collectively a reckoning for underlying systems that may not be fast or safe enough to handle a constant flow of data and transactions.

The fintech challengers have a decided advantage of speed and are attracting

"Fintechs that are free of legacy systems, existing ecosystems and some regulation are in a much better position to adapt to the radical changes that mobile and online technology are imposing on financial service," said Thad Peterson, a senior analyst at Aite Group. "It’s a lot easier to load up an API to get something going than it is to reprogram, or even rebuild an existing major banking system designed to serve thousands or even millions of accounts quickly and safely."

Like the

"Many of these systems have been around for decades, and for the most part do the job very well. The question going forward is can they continue to do it?" said Zil Bareisis, a senior analyst at Celent.

Bareisis has just finished a research on the legacy technology that is powering processing at financial institutions. Companies that rely on cards and wish to transform for the digital age must conduct an in-depth analysis and detailed planning to compete.

There are several problems with the pre-existing systems at most issuers.

Systems written in an old programming language, installed on premise that run on traditional mainframes are difficult to support, maintain and improve. And often, the original vendor no longer supports the system.

That creates pressure to reduce the cost of IT for aging systems as the people who know how these systems work retire. Worse yet, these challenges are paired with an increased expectation around payments, where and how consumers can pay, the speed of the transaction and the availability of information, according to Bareisis.

"The banks don’t have the flexibility, and their cost is going through the roof," he said. "So what can you do?"

There are other factors. Regulations such as PSD2 open the door for account to account payments, challenging the card rails. As part of the new data sharing rules, regulators are demanding performance levels which are difficult to attain with legacy infrastructure, such as the requirement to settle faster than a batch process allows, Bareisis said.

A simply plug-in isn't enough. "You can put in a real-time payment engine, but everything is happening in real time," Bareisis said. "That includes fraud monitoring, compliance, payments. All of that is in real-time mode."

The alternative models from fintechs feature cloud hosting, APIs and a de-siloed approach that improves time to market and is often easier and less expensive for merchants to use.

Newer companies, such as i2c and Marqeta, use open platforms that offer allow users to build solutions on the fly by accessing the technology companies' building blocks through APIs, supporting payments, analysis, marketing and other functions. Other companies like BlueSnap and Stripe use a cloud and API technology stack to "abstract away" payments complexity, Bareisis said.

There about 10 options for legacy companies to respond, and all carry at least some risk.

A full rebuild is expensive and prone to scope creep and delays; while outsourcing risks loss of flexibility. A less expensive option is to minimize the legacy system by adding more flexible technology on top, such as a payments hub or insulating the tasks of a legacy system to functions that require less speed, while using APIs for tasks that require more agility. There are also ways to manage legacy systems by adding layers of technology that address gaps or improve interoperability between systems. Bareisis categorizes some of these options as "for the time being," suggesting further work in the future.

The likely outcome is a strategy that cedes some competitiveness in the name of collaboration.

"A lot of the banks are finding the answer is 'not by themselves,' " Bareisis said. "If you leave them by themselves, they won't be able to do everything they wanted."

Traditional issuing banks do have a non-technical way to fight back, mostly by using compliance leverage.

Whenever a

"If a fintech wants to be in 'banking,' then it needs a system that can address all of the federal and state requirements for delivering checking and savings," said Tim Sloane, vice president of payments innovation at Mercator Advisory Group. "This isn't solved by high-tech software. It requires process that address and remain current with a terribly complex regulatory environment."