In the Bahamas, a pastime called hopping — boarding the hundreds of planes that jump about the tropical island chain like skipping stones — is a joy for tourists, but a migraine for managing the islands' cash supply.

These money planes have to cover more than 700 islands spread over 500 miles. The central bank believes the solution is to digitize the Bahamian Dollar, using automated rails to distribute funds directly to people rather than relying on aircraft and ground staff to lug crates of notes and coins from island to island.

"The movement of cash is both expensive and challenging within our archipelago," said Allison Middleton, who's part of the Sand Dollar project management team for the Central Bank of the Bahamas. "Large volumes of cash cannot be flown on commercial airlines or boats, but require private charters with private security."

Named for the sea creature that's

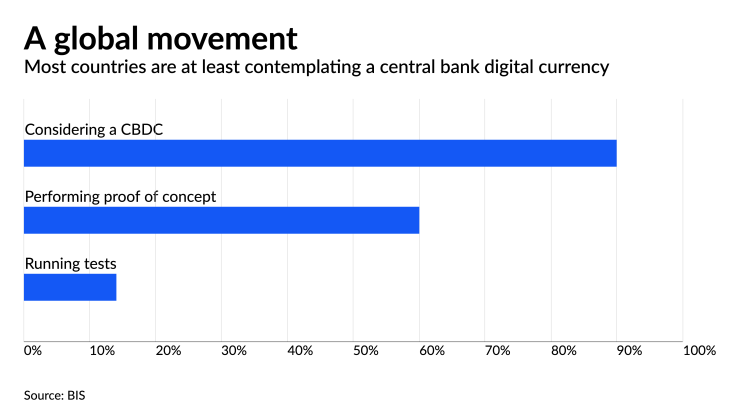

While most of these projects are conceptual at this point, CBDCs perform two functions. Wholesale CBDCs are designed for financial institutions to streamline payments and securities settlements. And retail CBDCs are aimed at consumers, enabling a digital equivalent of traditional currency.

A recent

Digitally divided

Though CBDCs are a global phenomenon, countries have their own distinct reasons to digitize their currency. China is competing with the U.S. Dollar's reserve currency status by digitizing its yuan, and the U.S. considering ways to improve government payments through a digital dollar.

But the underlying reason in most cases is it's becoming expensive to manage cash in economies that are increasingly dominated by

“There is every indication that central banks will continue to publish CBDC-related research well into 2022, as more central banks announce interest in examining the potential benefits and potential implementations of CBDCs," said Jackson Mueller, director of policy and government relations at Securrency, a Washington, D.C.-based company that builds technology to underpin distributed finance apps.

Early adopter

The Bahamas released a CBDC in October 2020. Like most concepts for central bank digital currencies, The Sand Dollar is a digital version of the country's traditional money, rather than a cryptocurrency. It can be accessed on a mobile phone via an iOS or Android app, or a physical payment card.

The Central Bank of the Bahamas built the infrastructure and technology to manage the Sand Dollar, and regulated banks are authorized to enroll consumers through their own applications, either for their own customers or unbanked users.

Read more:

While the central bank does not directly distribute funds, there are two tiers to accommodate the mix of banked and unbanked consumers, and to manage the mix of digital and traditional currency. One version does not link to a bank account, and has a $500 e-wallet holding limit and a $1,500 monthly transaction limit; the other does link to a bank account, and has an $8,000 e-wallet holding limit and a $10,000 monthly transaction limit. U.S. and Bahamanian dollars are roughly equal in value.

Tourists and other visitors access the Sand Dollar by contacting an authorized financial institution, downloading the connected mobile application and funding their wallet.

"Having a physical financial services provider on each populated island has never been feasible," Middleton said. "Eliminating the dependency of physical banknotes and coins will ease commerce within the country, but specifically within the more rural family of islands."

While much larger countries like are drawing most of the attention for their CBDC research and development, there will likely be more immediate progress on CBDCs in Latin America, Africa and emerging economies in other regions, according to Antony Welfare, executive director at NEM Software, a Gibraltar headquartered technology firm. Welfare is also an author who specializes in blockchain, and he is a contributor to a Digital Pound task force at Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs and The City of London.

For example, the

"These countries already have payment systems that are akin to CBDCs, that rely heavily on mobile," Welfare said.

Slow and steady

Larger countries are also moving forward, responding to China's progress with its

France's central bank recently started

The ability to accommodate trade and cross-border e-commerce will be key to determining the viability of any CBDC, explained Todd McDonald, co-founder of R3, a New York-based blockchain consortium. Blockchains have already proven their utility in moving money internationally and government digital currencies will need to do the same to be considered viable, he said.

"Only those that can simultaneously provide the level of scale and security and programmable compliance to make digital cross-border transactions a reality will prove viable," McDonald said.

Welfare, who has worked on several CBDC projects, says the central banks of larger countries like the U.S. and U.K. have

The pace may seem slow. Most CBDC initiatives have a four to five-year timeline. But there are a lot of challenges central banks have to address, such as the impact on monetary policy, and details on the role of partners in the private sector, said Adam Gilbert, a New York-based regulatory head of PwC's financial services advisory service.

There's also the distinction between electronic representation of bank notes and a digitized virtual currency that has to be determined, Gilbert said. "That's not to say CBDCs are a bad idea but in the U.S. we've had monetary policy for a long time. And even though most money today is electronic, it's still not a digital currency."

There are additional concerns about CBDCs, including the role of private banks and the fear that consumers will drain traditional bank accounts by aggressively switching to digital currency.

Writing for

Officials at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and Israel’s central bank have questioned the need for a retail CBDC if more traditional updates and upgrades to existing payments systems match, if not outweigh the purported benefits of a retail CBDC, according to Mueller. "It will be interesting to see whether this skepticism continues into 2022,” Mueller of Securrency said.

But the counter argument is that a digitized government currency would bring more people into the financial system by reducing the reliance on traditional bank branches, ATMs and cash. Digital currency could also be a foundation for promoting the adoption of more complex payment technologies.

"Once individuals have access to central bank money in a digital format, they will be more comfortable with using other digital currencies, including cryptocurrencies and stablecoins. Trust is a key pillar of adoption which can foster mainstream adoption from a wide range of participants across demographics and cultural backgrounds,” said Craig Perrin, vice president of sales at METACO, a Lausanne, Switzerland-based digital asset trading company.

CBDC vs. cryptocurrency

As bitcoin gained prominence over the past year, it's had an indirect impact on other digital assets that use distributed ledgers such as blockchains, including stablecoins and central bank digital currencies.

Stablecoins (which tie their value to a government currency) and CBDCs owe their development in part to bitcoin, given the perceived threat cryptocurrency poses to traditional monetary policy. As companies like

The CEOs of both

Stablecoins are used as a hedge against the volatility of cryptocurrencies that are used primarily as an investment asset, such as bitcoin. The card brands have developed technology that would allow connections between card payments and stablecoins, as well as CBDCs.

Most CBDC models, such as the Sand Dollar, use financial institutions to support distribution. A future digital dollar stimulus check would likely be issued by a bank using the card networks' rails, rather than consumers having a direct account with the Federal Reserve. This pressures banks to have a digital asset strategy that considers a future that includes stablecoins and CBDCs.

Along with the expected launch of Diem, the Facebook-affiliated stablecoin, and existing private stablecoins such as Circle's USDC, there's added momentum for CBDCs to serve as a government-backed alternative to crypto.