Before taking over Affiliated Bank in 2018, Sam Susser led a family-owned fuel distribution business, ultimately selling it for $1.8 billion. It's a success he's loath to repeat.

The selling price was “a multiple that was much higher than any multiple of cash flow that had been paid for convenience stores to that point — our bankers, board and outside lawyers felt it was so record-breaking that we really had a fiduciary duty to accept," Susser said.

“I literally cried like a baby at the closing table. … It so broke my heart,” Susser said. “That was my blood, sweat and tears for 28 years.”

Seven years later, at a new company in a different industry, Susser sees an opportunity he believes is just as big as the one he took advantage of to build a convenience store empire 20 years ago.

Texas’ big established banks are feeding off the supercharged growth the state is enjoying, but it’s further distancing them from smaller clients as they add scale, Susser said. He is convinced the trend is creating an opening for his bank. And if merger-and-acquisition activity heats up — as many observers predict — it could serve to shine an even brighter spotlight on a family-owned bank led by an ownership group determined to remain independent.

Susser is positioning the institution to take advantage of the market gap he senses. Last month, he hired a team to lead an expansion in San Antonio. The goal is to build a presence in all of the state's major metropolitan areas.

“We saw an opportunity in a rapidly consolidating space to build a Texas-owned, Texas-based bank geared toward the middle market,” Susser said.

Founded in 1959 as Affiliated Federal Credit Union, the Arlington, Texas-based organization converted to a depositor-owned thrift in 1998 and a stock-owned bank three years later.

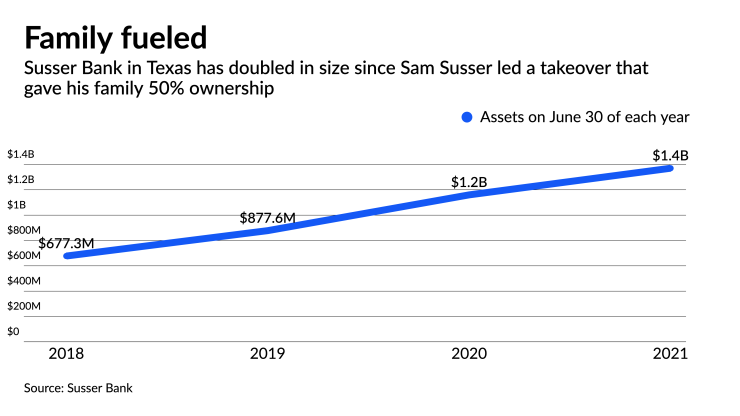

Susser led a group that acquired Affiliated July 2, 2018, and became the bank's chairman. His family owns about 50% of the company, and Susser plans to keep that stake in the family. In May, the $1.4 billion-asset institution rebranded as

“We’re excited about building a company that will be multigenerational,” said Susser, who also became the bank's CEO last month.

Susser, which operates four branches in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area and one in Round Rock, near Austin, faces heated competition in Texas.

“There are a lot of great banks here that are so successful,” Susser said. "They’re getting so darned big.”

But with that size comes inertia, Susser said. "They just aren’t as nimble and close to their clients as they were when they were $3 billion or $4 billion of assets … they’re walking away from middle-market clients” whose credit needs fall in the $2 million to $15 million range, he said.

Family history

The original family business, Susser Holdings, was involved in wholesale and retail fuel distribution as well as real estate development. It lasted 85 years until it was sold in August 2014, after getting an offer from Energy Transfer Co. that was too attractive to refuse.

Susser took the helm of the family enterprise in 1998, at the bottom point of a deep regional recession. Under his leadership, Susser Holdings invested heavily in retail fuel distribution, building a chain of more than 630 gas station convenience stores in Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma. It also developed a quick-service Mexican restaurant concept, Laredo Taco Co.

Susser hopes to keep the bank family-owned for at least as long as the fuel company existed. Susser Bank's website proclaims it is “built to last, not to sell.” The rebranding was intended to reinforce that message.

Susser admitted the new name led to a “split decision” inside his family, where his wife and one of his three children “are incredibly committed to being low profile.” Though the company considered several other options, it ultimately concluded none packed the punch of the family name, which links the bank to the Sussers’ long history of entrepreneurship.

“Frankly, we’ve done tens of billions of dollars of business with Texas-based companies and have always been maniacally obsessed with how we handled ourselves,” Susser said. “We couldn’t come up with a name we thought would be more helpful in terms of opening doors, recruiting people and recruiting clients.”

Lee Bradley, senior managing director at Community Capital Advisors in Duluth, Georgia, said the kind of not-for-sale declaration Susser is touting is not unprecedented. It doesn’t always act as a shield against offers from suitors, either.

“It’s kind of like Murphy’s Law,” Bradley said. “They’re the ones that [get] courted most.”

At the same time, positioning the bank as a long-term player inside a rapidly consolidating industry will likely carry weight with Texas business owners, Bradley added. Texas entrepreneurs “like community banks,” he said. “They want to size you up, know who they’re doing business with.”

Paul Schaus, chief executive of CCG Catalyst Consulting Group in Phoenix, largely agreed. While a bank’s ownership doesn’t matter to a lot of people, the ones likely to be the most sensitive to Susser Bank’s new message happen to be the ones it’s most interested in courting, according to Schaus.

“When you’re a small-business client who has a loan or a line of credit and a great relationship with a lender, you get nervous” about change, Schaus said. “A new management team or different lenders might not know the client as well, or they might have a new process that adds friction.”

Messaging will be key. Susser’s built-to-last tagline offers “a huge opportunity to create messaging and a story that could resonate with entrepreneurs,” said April Rudin, CEO of the Rudin Group, a New York-based financial services marketing firm.

“There’s plenty of white space for this type of bank,” Rudin added. “The win will happen if their message is client-centric and demonstrates how their offerings connect with entrepreneurial pain points.”

Path to banking

While Susser profited significantly from the sale of Susser Holdings, he never seriously considered retiring. “I was 51 years old,” he said. “I didn’t want to be a family-office guy that just invested in other people’s deals. I wanted to build another company.”

Banking seemed a natural option. Susser had worked three years as an investment banker at Salomon Brothers after graduating from the University of Texas, and the long years in business had produced healthy respect for the profession within the Susser family.

“When my grandfather passed away in the early 1990s, he asked for his bankers to be his honorary pallbearers,” Susser said. The family also hosted a lunch for those bankers as a thanks for their 50 years of working together.

Susser hired an investment banker, who introduced him to the top executives of nearly two dozen Texas community banks, including Garry Graham, Affiliated Bank’s longtime CEO.

Affiliated “had good bones,” Susser said. “I found a group that I was really excited about, that I thought could be the platform to help us build a really interesting company.”

Since taking over, Susser has worked to reposition the organization as more of a traditional commercial bank. Affiliated had been profitable under Graham, generating $26 million in the three and a half years before Susser’s arrival. However, its loan book was concentrated in construction-and-development, commercial real estate and residential mortgage lending. Construction-and-development loans made up nearly a third of the $568 million loan portfolio on June 30, 2018.

“The board felt the regulators weren’t going to let them keep growing with all that concentration,” Susser said. “All the eggs were in one basket.”

Graham stayed on at Susser Bank after the change in leadership. Rather than scale back the money-making construction-and-development business, Susser’s goal has been to grow the other parts of the bank around it.

The strategy appears to be working. Though its investment in construction-and- development lending remains substantial, it amounted to just under 20% of Susser’s portfolio — excluding Paycheck Protection Program loans — on March 31 of this year. Meanwhile, the commercial-and-industrial portfolio has doubled in size, to $85 million.

Building a legacy

For now, Susser’s plans for organic growth in the big Texas markets he is targeting. Still, acquisitions are possible, especially if the deposit market tightens.

“The industry is awash in liquidity and deposits,” Susser said. “That’s not going to last forever. … When the pendulum swings, we will probably be interested in [acquiring] deposit-rich franchises.”

An initial public offering is likely also in the cards, though Susser is quick to add a stock sale won’t alter the bank’s long-term strategy.

“Public companies don’t all manage for the short term,” Susser said last month during an interview on a Dallas radio station. An IPO, moreover, would offer other investors an opportunity to cash in their stakes, Susser said.

“In the long run, the only way I see that is practical for us to have a multigenerational company is to perform well and to have a pathway to liquidity for our outside investors,” Susser said. “I think we’ll continue to finance growth with private capital for a while, but someday we’ll tap the public markets.”

With barely three years of banking experience under his belt, Susser can still be described as a novice, but as a CEO seeking to build a middle-market bank, he possesses one key insight: He knows how it feels to lead a small business struggling to realize its growth potential.

“Our business was so bad in the late 1980s and 1990s, it would be routine for me to have to make 10 or 20 requests before I could find someone to lend us the money we needed,” Susser recalled. “Now I’m on the other side of the table. I have tremendous empathy for entrepreneurs and all they go through to cobble together a business.”