The murder of George Floyd shocked the national psyche to its core, spotlighting the persistent, systemic racism that exists in many American institutions, which continues to disenfranchise those who live within the Black community.

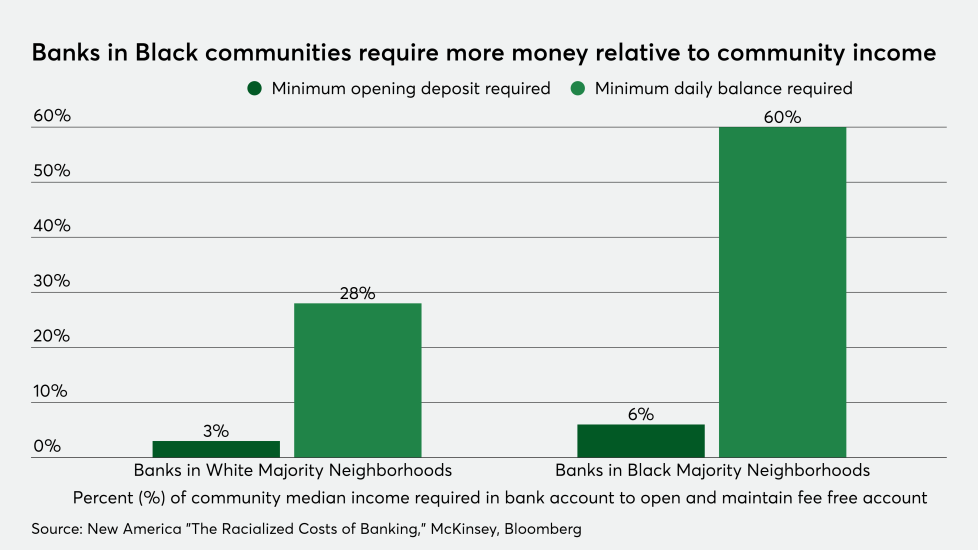

The national and international outcry for reform has been strong. However, there is one institution that can take immediate action to make mainstream products accessible, life more affordable and the pursuit of a middle class dream attainable.

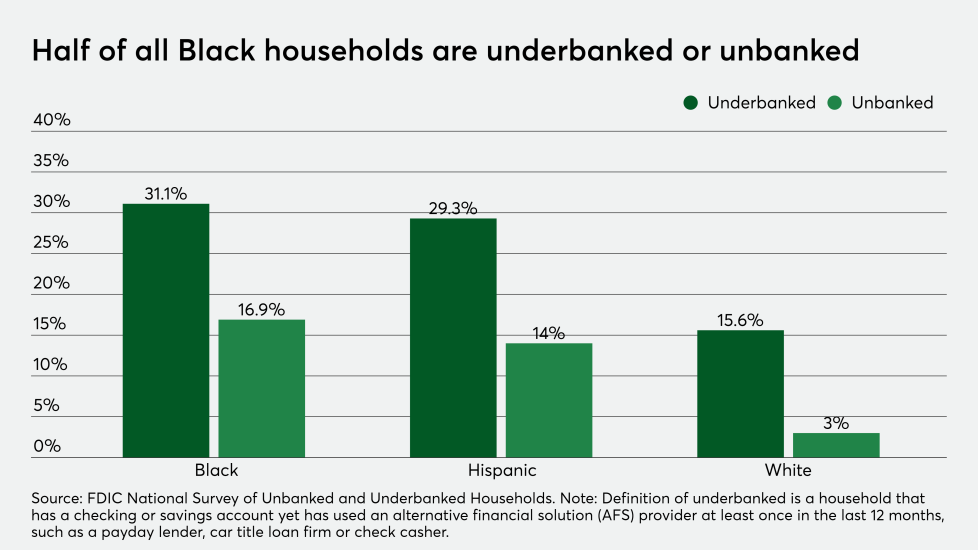

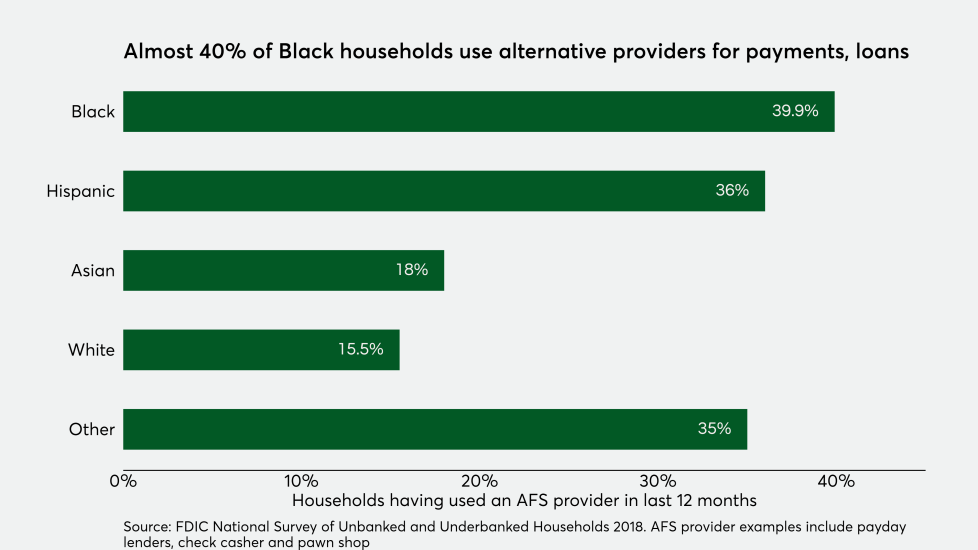

At the center of this institution resides the payments industry, supported by traditional banks, credit unions and credit card issuers, along with nontraditional firms such as pawn shops, payday lenders and check cashers.