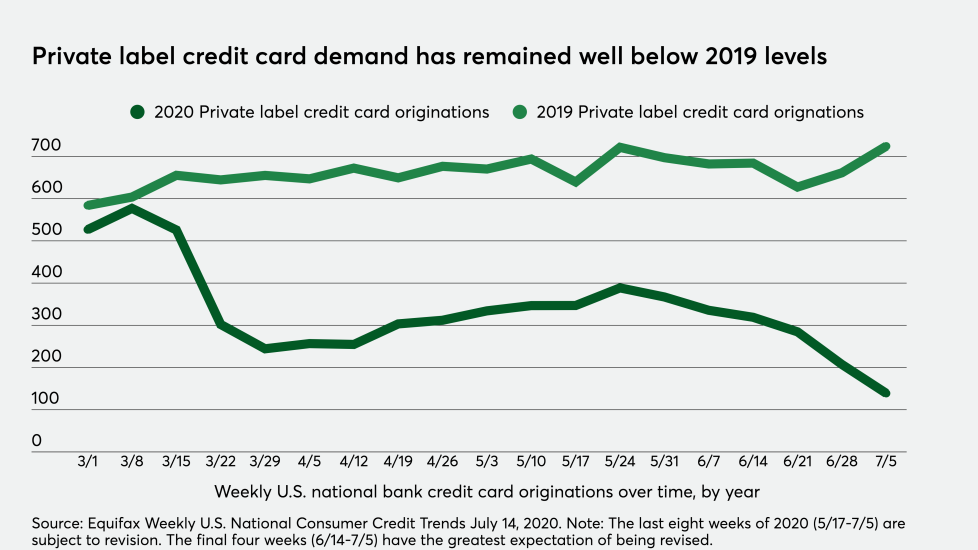

Cash usage dropped much lower due to the coronavirus pandemic, and it appears that credit cards may be exhibiting some signs of abandonment as well.

Consumers are dialing back on applying for credit cards and reducing balances possibly because there are fewer opportunities to spend money, but perhaps also in case there is a stronger economic downturn later this year or next.

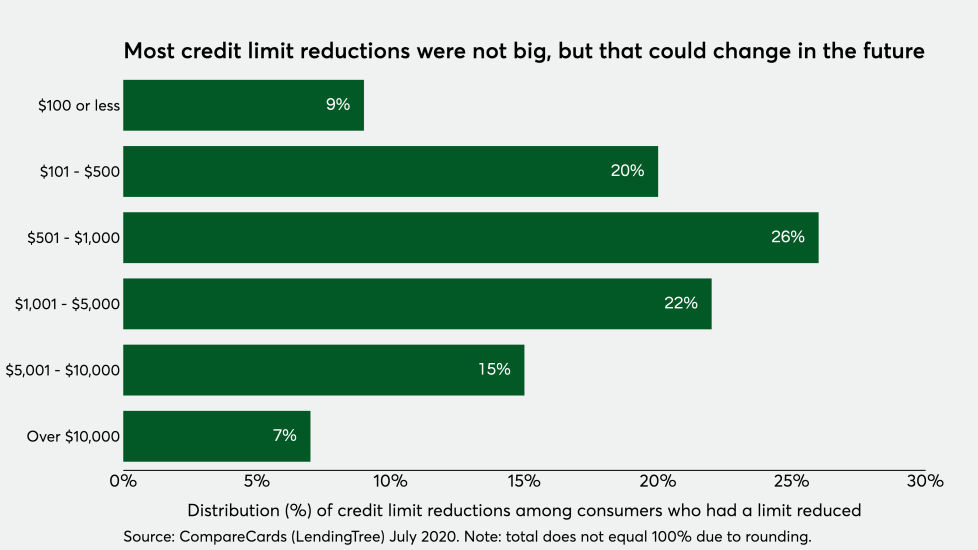

Meanwhile, card issuers are bracing for a potential financial storm as a wave of mass layoffs looms on the horizon, especially in airline, hotel and other industries. As a result, some card issuers are looking at their existing portfolios and taking preventative measures, such as trimming inactive cards. Even digitally-focused companies like Apple, which reported satisfactory adoption for its

“In many cases, if a card isn’t being used, a bank isn’t making any money off of it,” said Matt Schulz, chief credit analyst at CompareCards by LendingTree. “That’s not a huge deal in good economic times, when delinquencies and defaults are rare, but when things go south, the calculus changes. Issuers then see that card and its unused available credit as little more than unnecessary risk, so they may choose to reduce the card’s spending limit or close it altogether. That’s what’s happening today and will likely continue to happen in the near future.”