Now that the U.S. is five months into the COVID crisis a new victim is emerging. Caught between small businesses furloughing their staff landlords needing to collect rent are millions of

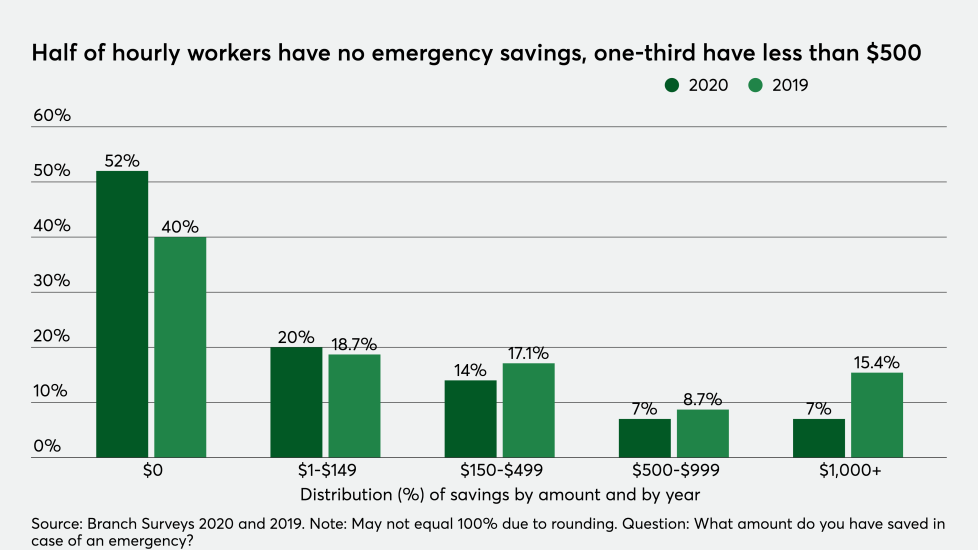

Record unemployment levels, reductions in hours available to work and a stimulus package that has seen its funds used up has meant that many hourly workers are struggling to make ends meet at a higher level than before the pandemic. Having to choose which bills to pay and where to obtain funds to buy groceries or pay rent has left this segment of the workforce vulnerable. The recent spate of

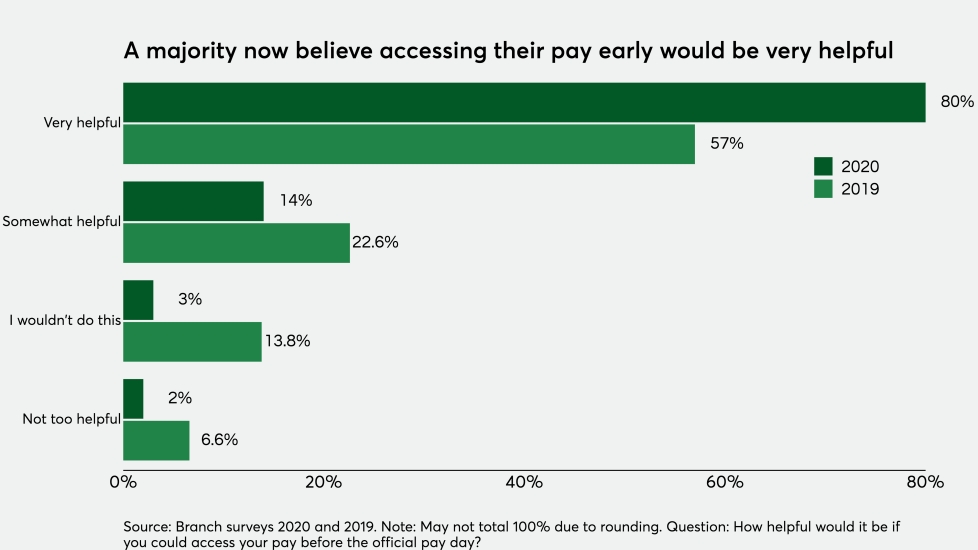

Now caught in a vicious bill pay spiral, it appears that the payday lending industry stands to gain — while also creating bigger debt problems for this audience down the road. But a host of new and existing fintechs, ranging from challenger banks to