The two-week pay cycle, while common today, has been around only 80 years or so. Dr. Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor at UCSB, reported on

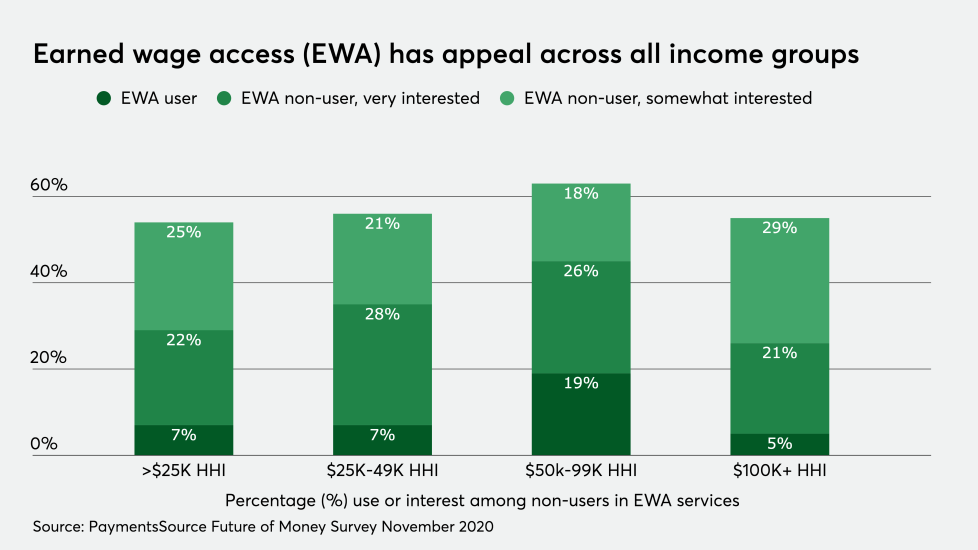

“It doesn’t work anymore,” said Atif Siddiqi, founder and CEO of Branch, an earned wage access (EWA) provider that offers on-demand pay. “The traditional, every two-week payday has begun to change. The next evolution is on-demand pay which is based on when workers need it. I see on-demand pay as being the standard for paying hourly workers in the next three years.”

While there has been a general trend of paying people faster for work already performed, starting with