We can go a long way to preventing another Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) fiasco with a simple requirement that banks disclose how future changes in interest rates will affect the value of equity. With this requirement the market would help quickly discipline any bank taking excessive interest rate risk. The result would be a much safer banking system without increases in capital requirements or more supervision.

What caused the dramatic collapse of Silicon Valley Bank? The reasons are all too familiar to students of banking history. SVB's managers were gambling on short-term interest rates remaining lower than long-term rates, investing heavily in long-term mortgages and government bonds funded with short-term deposits. The sharp increase in interest rates caused asset values to plummet, eroding the bank's equity capital. As during the 1980s — when bets on interest rates led to the S&L crisis and the near bankruptcy of the mortgage giant Fannie Mae — it was a classic case of purposeful "duration mismatch" between assets and liabilities. The strategy would be profitable if rates stayed flat or fell, and if not, the government would share in the losses.

While the mechanics behind SVB's failure are straightforward, it is much harder to understand why it was allowed to happen. Commercial banks like SVB are highly regulated. The bank's larger investors and regulators were reportedly well aware of its elevated risk exposure. Unlike credit risk, interest rate risk exposure is relatively easy to identify, quantify and hedge against. It was no secret that the Federal Reserve was committed to a series of rate hikes to combat inflation, or that longer-term rates could rise sharply if investors came to believe that inflation would persist.

Were SVB's regulators asleep at the wheel? While perhaps they had the discretion to do more, there appears to have been no explicit rule that should have been enforced but wasn't. In fact, surprisingly few regulations are directed at formally measuring and controlling interest rate risk. Bank capital requirements are primarily linked to credit risk. In response to SVB's failure, liquidity requirements were expanded for medium-size banks such as SVB, but still no requirement addresses interest rate risk head-on. Regulatory stress tests, which take interest rate conditions into account, may not always incorporate scenarios with rapidly rising rates. (Some have suggested that stress tests failed to alert regulators to the situation because of the focus on scenarios that feature heightened credit losses. Credit losses tend to occur in downturns, when rates are falling rather than rising.)

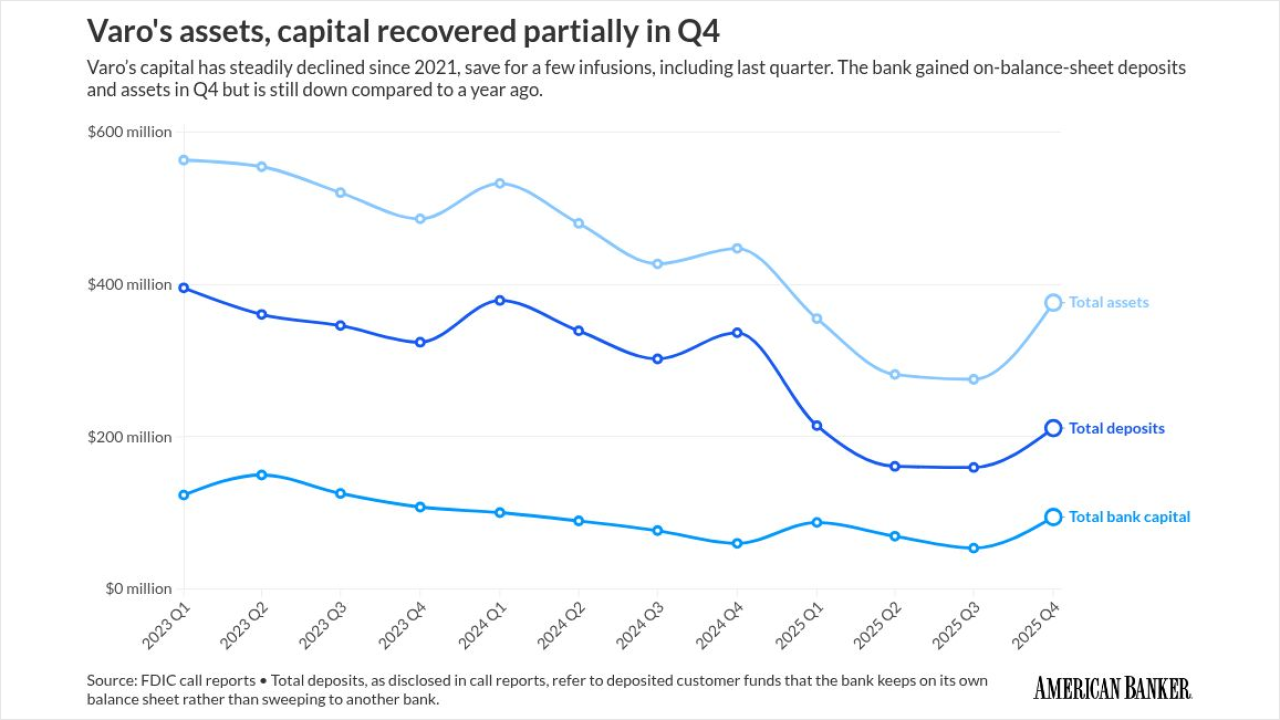

The recent round of terminations comes after the neobank cut 225 employees in January.

Although the S&L bailouts and near-bankruptcy of Fannie Mae in the 1980s did not give rise to the direct regulation of interest rate risk, it did cause a significant change in the disclosure policies of the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The GSEs agreed to regularly report their duration gap in their quarterly financial statements. The duration gap is roughly proportional to the losses that would result from an upward shift in interest rates (technically, a parallel shift of the yield curve). Not only did adopting this disclosure policy make it much easier for regulators and investors to gauge the GSEs' risk exposure, but it also changed behavior. When interest rate risk-taking became more transparent, the GSEs voluntarily did less of it.

Our modest proposal is to require medium and large-size commercial banks to regularly report their duration gap in their quarterly financial statements. The disclosure would make it more apparent to regulators and investors when a bank is taking significant interest rate risk. It would serve as an incentive to limit interest rate risk in order to avoid regulatory action and bad publicity.

The duration gap provides new information that even the most astute market analysts would not be able to infer from currently mandated disclosures. Technically, calculating the gap requires knowing the maturity structure of a bank's assets and liabilities and the effects of swaps and other derivatives on that maturity structure. Banks already have all the necessary information to do that calculation, making the incremental regulatory burden modest.

Shareholders are likely to make it quickly known to management that reaching for short-term profits by riding the yield curve (lending long and borrowing short) is not a viable long-term strategy. These disclosures will also provide the Federal Reserve with useful aggregate information into the health of the banking system next time it begins to raise short-term rates. The direct and low-cost way to prevent it is for banks to disclose their duration gaps. As the British say: Mind the gap.