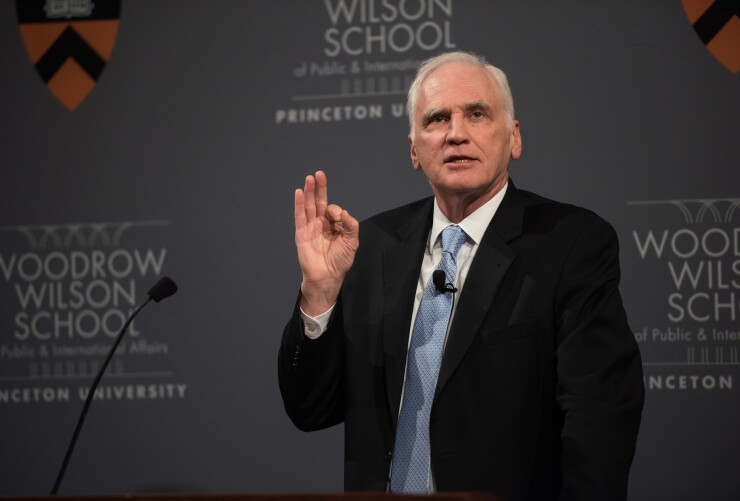

Back in 2017 I took a trip to Princeton, N.J., to

In that address, Tarullo said that the utility of stress testing as a pass/fail exercise may have already run its course, suggesting instead that "the supervisory examination work around stress testing and capital planning [be] completely moved into the normal, year-round supervisory process." Tarullo added that the qualitative aspect of the test — where banks retain post-stress minimum capital levels but the Fed still has reservations about how banks show their work — has limited value, especially

Tarullo, who has not served in government since that speech, has nonetheless not stopped thinking about the appropriate role of stress testing in bank supervision. In a

If you're reading this, you either are hopelessly lost on the internet or already know the basics of what stress testing is. But for those who have wandered in from elsewhere, here it is: Stress tests take each applicable (read large) bank's balance sheet and run it through a proprietary model to see how each bank will perform under a hypothetical but very bad economic scenario, akin to the conditions banks experienced in the gooey kablooie of 2008. In the initial iteration of this regime, banks that came out of that hypothetical episode with at least the minimum capital levels required passed; those who did not failed, and would have to restrict their dividends and retain capital until they passed.

But Tarullo now argues that the biggest problem with stress testing — particularly as a means of assigning a bank's capital levels — is that it relies on a single hypothetical severely adverse scenario to determine how much capital banks will need to retain. That scenario is almost by definition not the kind of real-life severely adverse scenario banks

The answer then might be to add additional scenarios to diversify the kinds of stresses that banks might face. But that invites another problem — which of the scenarios should be the binding one for capital purposes? Certainly an imaginative staff at the Fed could devise scenarios ranging from a mild recession to the extinction of life on earth, but assigning a binding constraint somewhere in between is arguably just as arbitrary as having a single scenario.

Tarullo's conclusion — and a worthwhile policy debate that he is hoping to incite — is to make the stress test scenarios greater in number and more diverse in their nature and therefore more capable of picking up idiosyncrasies at individual banks or across the industry, but simultaneously decoupling those stress test results from actual minimum bank capital ratios.

"One realistic option is to decouple the annual stress test required by the Dodd-Frank Act from setting the regular, ongoing capital requirements of large banks," Tarullo writes. "That is, the SCB framework would be eliminated, and the binding capital requirements of large banks would generally be those set forth in notice-and-comment regulations. However … the stress test results could be used to inform both changes in those regulations and possible issuance of directives requiring specific banks to increase their capital ratios because of significant idiosyncratic risks."

While there is no wrong way to eat a Reese's, there seems no right way to establish minimum bank capital requirements. The shortcomings of a capital regime where supervisors comb through each bank's books individually and alight on a number between 0 and infinity is nimble and bespoke but also arbitrary and inconsistent; a regime where everyone has the same capital ratio is consistent but ignores the highly variable nature of different banks' business models and commensurate risk. These approaches are both valid and must be considered when setting capital levels, but they are also necessarily in tension — and always will be.

The stress capital buffer squares that circle by having a defined regulatory process that yields individualized results, which on its face isn't a bad compromise. But it necessarily treats the stress test itself as an oracle rather than what it is: a way to discover problems on banks' balance sheets — both individually and collectively — before it's too late.

Stress testing is rightly held up as perhaps the single most transformative innovation in bank regulation since the foundation of the Federal Reserve. But it is not a panacea, and tethering the outcomes of the stress tests to bank capital perhaps absolves policymakers of their obligation to periodically weigh and adjust those capital levels — and owning the results.