The sharp slowdown in commercial and industrial lending over the last six to nine months is worrisome. But there is more to this story than meets the eye.

Some believe that increased bank regulation and tighter supervision is behind the lending slowdown. Yet that assessment misses some important details. Indeed, there is no “smoking gun” in the data linking the decline in the annual C&I loan growth rate to either passage of the Dodd-Frank legislation or the Federal Reserve’s progressive tightening of its stress-testing requirements.

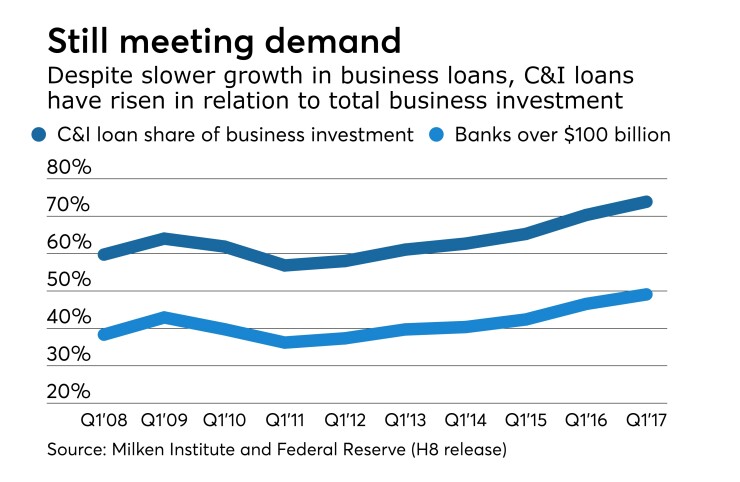

Digging deeper reveals two more nuanced takeaways. First, it appears a pullback in overall business investment by potential borrowers is a more likely reason for the decline in C&I loan growth. Secondly, evidence does point to the tighter regulatory environment having an effect on C&I lending. But that effect has more to do with the types of commercial loans banks have made, not overall loan growth.

The reasons behind the sluggish C&I lending matter for more than just the banking industry. Business loans are usually an important source of funding for business investment, and a critical factor shaping the outlook for economic growth. In some cases, slower lending rates may threaten the ability for small to midsize businesses to expand operations and create jobs. Bank lending is especially important for smaller businesses that are unable to fund investment by issuing bonds or stock. Small to midsize businesses in particular are the engine of job creation.

C&I loan growth has fluctuated since the crisis and recovery, and has been on a gradually downward slide since 2012. But that rate has fallen sharply since late 2016. The annual C&I loan growth rate declined from an average pace of 11% during the 2012 to 2015, to only 4.2% in the second half of 2016. (Data in this article uses seasonally adjusted annual rates.) According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., quarterly C&I loan growth peaked at $72 billion at the end of the first quarter of 2016. It declined sharply in the next two quarters to $18 billion and $12 billion. In the fourth quarter, C&I loan balances were $7 billion less than the previous quarter.

It may be tempting to raise alarm by blaming the regulatory environment for the lending slowdown, and in turn a slowdown in business investment.

But the data tells a different story: Business investment sputtered well before C&I lending slowed, suggesting that low loan demand is the primary culprit. Companies’ investment spending has nosedived, falling far below its post-recovery (2010-12) pace in 2015 — from an average annual pace of 1.2% during 2012-15, to an average of 0.4% in the second half of 2016 — despite interest rates having declined to historically low levels.

Investment did not slow because funding was too expensive or not available. It slowed because businesses were (and remain) reluctant to invest and add capacity.

Evidently, the C&I lending slowdown is a demand-side, not a supply-side story. Slower growth of bank credit was not a constraint on investment. Rather, businesses have faced weak demand due to the tepid recovery. When firms are not utilizing fully their existing capacity, responsible executives are hard pressed to justify borrowing funds to expand. Moreover, even if they were so inclined, they have no pricing power to increase profit margins to pay for such borrowing.

Yet the data does not let the regulatory environment off the hook.

Two disturbing trends in bank C&I lending have emerged since the implementation of the onerous and complex Dodd-Frank Act banking regulations, which may indeed restrict smaller businesses from having access to bank funding. First, most of the rise in C&I loans since 2010 was attributed to originations by large banks — those with assets of over $100 billion, which roughly comprises the 25 largest U.S. banks.

Second, post-crisis regulatory and supervisory changes likely have incentivized banks to shift their lending in favor of large borrowers.

Banks of all sizes have turned away from making smaller loans. Loans issued for under $1 million have declined from financing 17.4% of business investment at the beginning of 2010, to only 12.5% at the beginning of 2017. By comparison, large-scale lending with loans over $1 million have increased their share of investment financing from 44% in 2010 to 56.5% at the start of 2017.

One can surmise that in the post-Dodd-Frank era, banks find it more cost-effective to issue large loans instead of small ones because they now face higher fixed costs associated with the tightened regulatory and supervisory requirements. At a minimum, operating costs have risen for all banks because of the additional training and paperwork required to show that they have established enhanced compliance, due diligence and reporting/verification procedures.

For large banks, there are additional requirements for legal loan workouts and documentation of legal ownership and succession structures for various parts of financial conglomerates in the event of a bankruptcy (e.g., the “living wills” requirement for Dodd-Frank). Also, large banks are being challenged by the Fed’s more stringent implementation of the Dodd-Frank stress tests and qualitative risk management procedures mandated by the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review.

Heightened regulatory and supervisory costs likely are causing banks to shift their lending away from small and midsize busineses toward customers who want to borrow in large amounts — over $1 million. Unfortunately, well-intentioned bank regulations aimed at ensuring a more robust banking system may have the unintended consequence of denying credit to firms responsible for most of the job creation in the economy.