-

The term has gone from a common brand name to a catch-all for innovative technologies in financial services to a somewhat patronizing plural noun to describe startups and their founders.

October 5 -

Bankers, investors and analysts stop short of declaring a bubble. But the fintech startup and investor fields are getting crowded, and there's bound to be a culling of the herd.

September 28 -

Can true innovation happen when so much of the industry is still working on systems built in the 20th century?

September 21

(By Bradley Leimer, as told to

There's much talk of "unbundling" in the industry these days. Bankers are fretting about startups nibbling away at their most profitable customers. New technologies from marketplace lending and robo-adviser platforms to real-time payments and the distributed ledger have the potential to dismantle core areas of our traditional business model, and more critically, connectivity to our customer value proposition. Depending on your point of view, the pace of fintech innovation is unsettling, maybe even terrifying to some. As I've long warned, with these changes,

But the reality is that banks unbundled themselves.

As usual, I'm getting a little ahead of myself. Let's back up a bit. I grew up in Silicon Valley in the 1970s and early1980s, as it was just becoming what it is today. I had friends whose parents worked at companies like Fairchild, IBM and Apple. Like many of my peers, my first experience with financial services was through a passbook savings account housed at my family's American Savings branch (now, after several mergers, part of JPMorgan Chase). My first "job" was delivering newspapers for the San Mateo Times. I remember riding my bike down to my bank branch several times a month to deposit money into that passbook account. With interest rates just over 6%, getting interest applied to that account was much more than the rounding error it is today.

I loved going to the branch to deposit money. It was like a present each time.

Over the years, I built a healthy savings balance and a great relationship with the bank's employees. As a typical teen, I felt that savings account start burning a hole in my pocket when I saw my first real financial "need" — it wasn't a car, it was the third generation Apple II.

Rather than wiping out a large portion of my hard-earned savings on this amazing new machine (the Mac would come out the next year), I took my parents' suggestion and went to our bank to see if they would give me credit to buy the computer. Much to their surprise, they did. I used my savings balance as collateral and got my first loan, and my new computer. I was 13.

While you might say that this is a silly example because banks would certainly make this kind of loan today, I have my doubts. I don't see many young adults, let alone teenagers, having a personal relationship with their bank. Banking before the nineties was different. You had nearly twenty five thousand financial choices (now you have less then half that) and some of the most interesting aren't banks at all. My family had almost all of their financial relationship with that one bank — our savings, checking, credit cards, mortgage, auto loans, everything. Back then it would have been inefficient for a consumer to have accounts in several banks. The technology and ability to maximize your financial relationship just wasn't there. Now a typical family has as many as nine different financial partners.

Why the change? How did banks lose this singular role in our daily lives? What happened to banking itself?

As I said, it was self-imposed.

Like in other industries, the unbundling of financial services seems to have started with the quest for deeper efficiencies and broader profit in response to increasingly complex regulation and demanding investor cycles. In the early 1990s, following the lead from banks like Citicorp, the industry started unbundling products into silos: First the credit card business, then the mortgage business, auto lending, small business, personal loans. Eventually all of the credit business was walled off from the rest of the deposit relationship. Deposit products, insurance and investment services became productized and segmented as well. The rationale was that it made more sense to have individual P&Ls by business line, improving product management and marketing focus, efficiencies, and profitability. And it worked well. Maybe too well.

While it looked good to the markets and our bottom lines, the effect was that we detached the connective tissue between a customer's accounts, obscuring the broader view of the very relationship consumers and small businesses had with their banks. Systems were segmented and specialized and were no longer able to provide a unified vision of our customer's relationship, even to bank employees. It was the same for the customer. When online banking came around, the credit card balance or the mortgage relationship did not show up online, even if it was at the same bank as the deposit account.

As we continued to unbundle the customer relationship and user experience with our increasingly complex set of financial products, external providers started to build more efficient businesses. When it was time for that consumer to make bigger-ticket purchases financed with instruments such as a mortgage, this business was fulfilled by nonbank credit companies which built better lead generation funnels, like Quicken Loans, Countrywide and its predecessors before the Great Recession. By now, mortgages and consumer credit products have become commodities. Add to this deposit products, from savings to IRAs to CDs, investments, insurance - all siloed and optimized — but not necessarily from the customer's viewpoint.

This was a big shift from how banking had operated up until a quarter of a century ago. It was the first unbundling of financial services. And it laid the groundwork for the second wave of unbundling by startups that we all talk about today.

In a sense, our industry wanted to provide focus to products like fintech does today — by creating teams specifically focused on targeted products. But we added typical layers of decision making that diluted the strengths of the startup across those disjointed business lines, often with competing goals. Banks, being so complex and focused on managing risk and compliance, couldn't let their teams attack a business problem the way a startup can today.

Banks today have scale, trust and runway. Startups have speed, flexibility, and focus. We need to learn from each other — and work with each other. In the pursuit of efficiency and focus, banks put too much priority on short-term profitability and not enough on understanding how the customer was leveraging a product or service — really understanding their overall needs and making banking simple, personal, and fair. The result has been a systematic disenfranchisement of our traditional customer base.

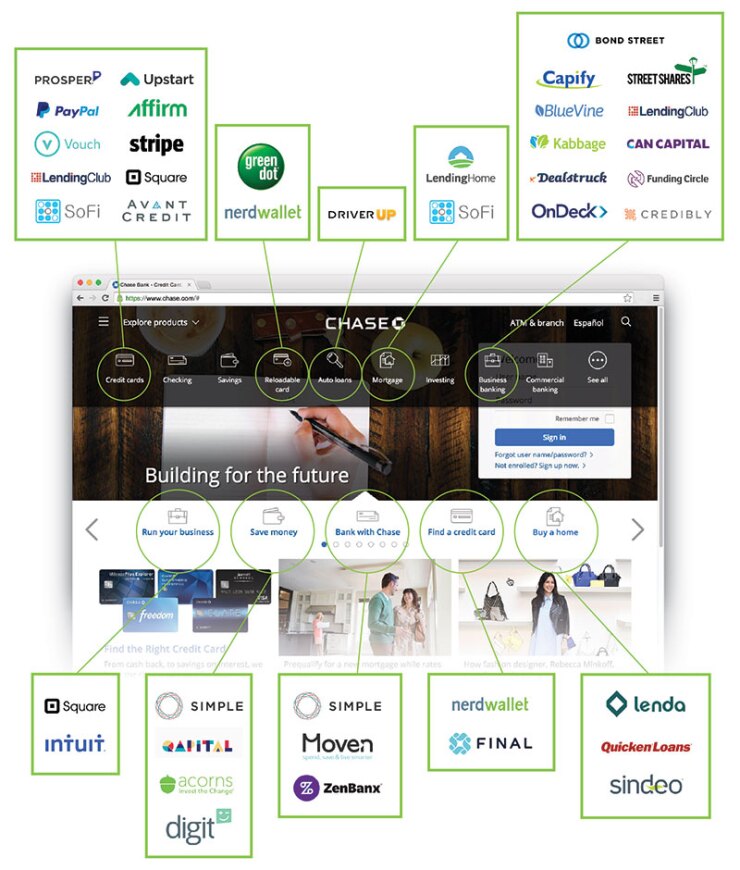

The graphic on this page, and similar ones that have been shared widely in fintech circles, illustrates that there's not a single business unit in a bank that is not being challenged in some form or fashion by a startup from outside. Student loans, credit cards, mortgages, deposits, the basic checking account, payments — none of these areas are not being encroached by a startup of some kind. Goldman Sachs' March "Future of Finance" report says it's plausible that up to 20% of industry revenues could be captured by external entrants.

The marketplace lenders, for example, are offering an alternative for small business owners who otherwise must wait three to four weeks or more to get a bank loan (if they can get one at all). By looking at different data points and evaluating a business' financials in a more systematic way, marketplace lenders can get the same thing done in hours or days. That efficiency does make a difference. Think about a restaurateur who needs to quickly replace a broken stove, or someone who needs to finance a couple of trucks to expand their business. It may not be the best deal for them, but speed counts. This is why we're seeing more nontraditional financial players from PayPal to Square to Google entering this credit marketplace space — it's good business to focus on small business.

To be fair, banks have consciously made strategic decisions to cede some of this business (such as subprime auto or small-business lending) because of the particular risks or inefficiencies. For the startups, profit margins aren't really the short-term focus. Right now they're building market share and mindshare. They've got two to four years to ramp up and buy into a business. Banks are looking at that and saying, "well, we may not want to be in that space." The problem with that attitude is, again, the banks are teaching another generation, as they did last time with credit cards and mortgages, that the first place to look for certain types of financing isn't a bank. It would be at one of these providers instead. A generation of consumers is learning that there are banking services from nonbank providers — whether that's PayPal or Venmo to move money, or alternative lenders like Lending Club. These are the same consumers who will be opening businesses and who will be running the companies of the future. Don't you think there is collateral damage to the industry as this generation takes the reins?

Once again, we're giving up too much of the relationship and not doing enough to aggregate loans and deposit products and places of value storage. We're not helping customers by advocating on their behalf, negotiating for better deals, for better rates, and related services. To be blunt, we're not looking out for their best interests.

Think about peer-to-peer lending. Using Lending Club as a proxy for the sector,

Yet I am optimistic. We can rebundle the bank.

Technology is now fully capable of doing all those things — aggregation, advocacy, advisory — on the individual level for consumers and for businesses. And that is frankly what we bankers should be looking to do. How do we do this? Collaboration and partnerships with the new fintech companies is the long-term play for banks. We need to continue to be involved in the development of financial technology — this is not the time to sit on the sidelines.

What would a rebundled bank look like from a consumer's viewpoint? Such a bank would give what I will call, for lack of a better term, a dashboard view of all of their services that are financial or tangentially financial. When I access my banking services, I should have access to my Lending Club loan or my Betterment account or other types of financial services that aren't necessarily offered by the bank. I should be able to choose — through my bank's use of flexible middleware like Germany's Fidor Bank already offers — to bundle any service that I want to, that I deem crucial to understanding my financial picture. That, in turn, if the consumer or business chooses to share the data, can help the bank make better product and service offerings, based on my preferences and other companies that I do business with. Right now, USAA does this very well. But I would take it even further.

Build a relationship based on the trust customers already have with the financial institution combined with an understanding of what's happening with their other financial relationships, an understanding of their preferences, patterns, behavior, financial activity. Make suggestions, aided by artificial intelligence, contextually at the right time and the right place — and not wait until after the consumer's already gotten a loan or another "financial" service from one of these other providers.

How many years have we been sitting on incredibly illuminating data about our customers — where people are purchasing, what type of companies that a business is interacting with, at the transaction level — and not leveraged that to its fullest extent? I don't think we positioned personal financial management well enough. Aggregation matters, perhaps now more than ever. The opportunity now is for bankers to become advocates for our customers, to make truly beneficial suggestions through our normal course of transactional occurrences. Banks need to refocus on making

There are a lot of companies that are exploring this advocacy space that are willing to collaborate with banks, companies that we can then could turn and learn from and help scale. A lot of these companies are looking to leverage their data and analytics tools to build and deploy them at large-scale institutions like ours. Understand that these startups not as threats but as experiments and R&D for the entire industry as our customer behavior quickly pivots. Celebrate and engage new fintech entrants, because, I guarantee you, the industry will look nothing like it does now in a less than a decade.

We are in an era of the rise of

While I do not think that this is banking's

Bankers' business is in play. Maybe even our heart and soul. But it's ours to lose.

Bradley Leimer is the head of innovation for Santander Bank NA. He brings additional perspective from prior work leading technology, marketing and business development teams in banks and credit unions and through a decade driving big data and database marketing analytic services for national and regional bank clients. His opinions are his own and not necessarily that of his employer.