Bankers will take good news anywhere they can find it.

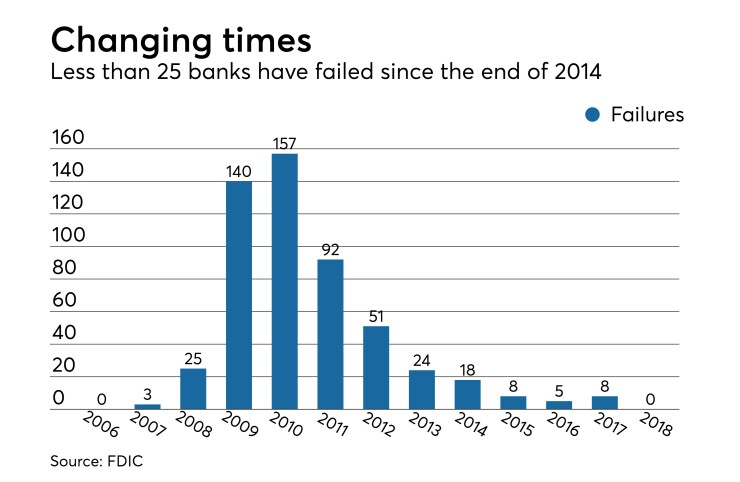

In another sign that the industry has put the financial crisis in the past, seven months have come and gone since the last bank was shuttered by regulators. It is the longest stretch without a failure since a 31-month run ended way back in February 2007.

The aftermath of the financial crisis sunk hundreds of banks and every Friday it seemed inevitable that one bank or more would fail. Sometimes liquidity was the culprit. Often credit issues, mounting financial losses and eroding capital were to blame.

The crisis caused a lot of introspection, along with a refocus on character, capital and capacity. Today's banking industry, by and large, seems to be stronger as a result.

“There was a weeding out process,” said William Black, an economics and law professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and a former senior deputy chief counsel at the Office of Thrift Supervision. “There was also simply some looking in the mirror and realizing actually the three Cs of credit would be good to concentrate on.”

A series of metrics help explain the recent dearth in failures.

Tier 1 risk-based capital ratios averaged more than 13% at March 31, marking an improvement from just over 10% in early 2007, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

The industry also has a better balance between loans and deposits. The industry's loan-to-deposit ratio stood at 89% in the first quarter. A decade ago, the average bank had $1.30 in loans for every $1 in deposits on the balance sheet, creating an elevated need for alternative sources of funding.

Finally, banks have worked hard to diversify lending after suffering huge losses tied to real estate, especially construction and development loans. At March 31, real estate loans made up almost half of the all credits, compared with nearly 63% in 2007.

“The banking industry is in really good health,” said Tim Yeager, a professor at the University of Arkansas and a former economist at the St. Louis Federal Reserve.

Yeager has developed his own stress test model that puts community banks through a recession even more severe than the most recent downturn. Under his model, a tenth of community banks would fail using their 2007 financials. The number drops to just 3% using current metrics.

Yet while there is a reason to celebrate, bankers must resist the urge to become complacent or take unnecessary risks. It is highly unlikely that the industry will enjoy another two years of failure-free existence.

Economic cycles do turn, eventually. And it is inevitable that the industry will fall victim to a new approach to banking that will go flat in a downtown.

It "takes a while for the financial system to come up with ever more creative ways to lose a bunch of money,” Black said in half jest.

Bank failures typically fall into two categories: Collapses tied to systemic turmoil and one-off situations that are unique to the institution, said Kevin Jacques, the finance chair at Baldwin-College and a former regulator at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

The last failure — December's closure of Washington Federal Bank for Savings in Chicago — seems to be an isolated incident. The small bank's implosion happened quickly, taking place in the wake of its CEO's suicide and days after being hit with a prompt corrective action notice barring executives from tampering or destroying documents.

It is a good bet that a handful of failures could take place in coming months despite an economy that continues to grow nine years after the last recession.

“There's some good news out there but I would hesitate to declare victory,” Jacques said.

An escalating trade war is a notable risk. President Trump, who has touted trade wars as “good, and easy to win,” has imposed tariffs on a variety of goods, provoking reprisals from targeted countries.

That could hurt the overall economy, specific borrowers and eventually banks. U.S. companies that lose business from recently imposed tariffs could have trouble repaying loans. Other businesses that relocate operations overseas could also take their banking relationships with them.

The greatest threat to financial institutions might be interest rate risk. During the savings-and-loan crisis, more than 1,000 institutions failed after issuing long-term, fixed-rate loans at yields below their funding costs.

Banks are at risk of finding themselves in a similar position as the Federal Reserve raises rates, albeit it at a slower pace. There is the chance that some management teams could be caught flatfooted.

“Any good financial institution is well aware of what's going on today and is looking not only into the remainder of this year but also into next year and asking where will interest rates be?” Jacques said. “How far and how fast will they rise? It is better to be proactive than reactive.”

Bankshot is American Banker’s column for real-time analysis of today's news.