-

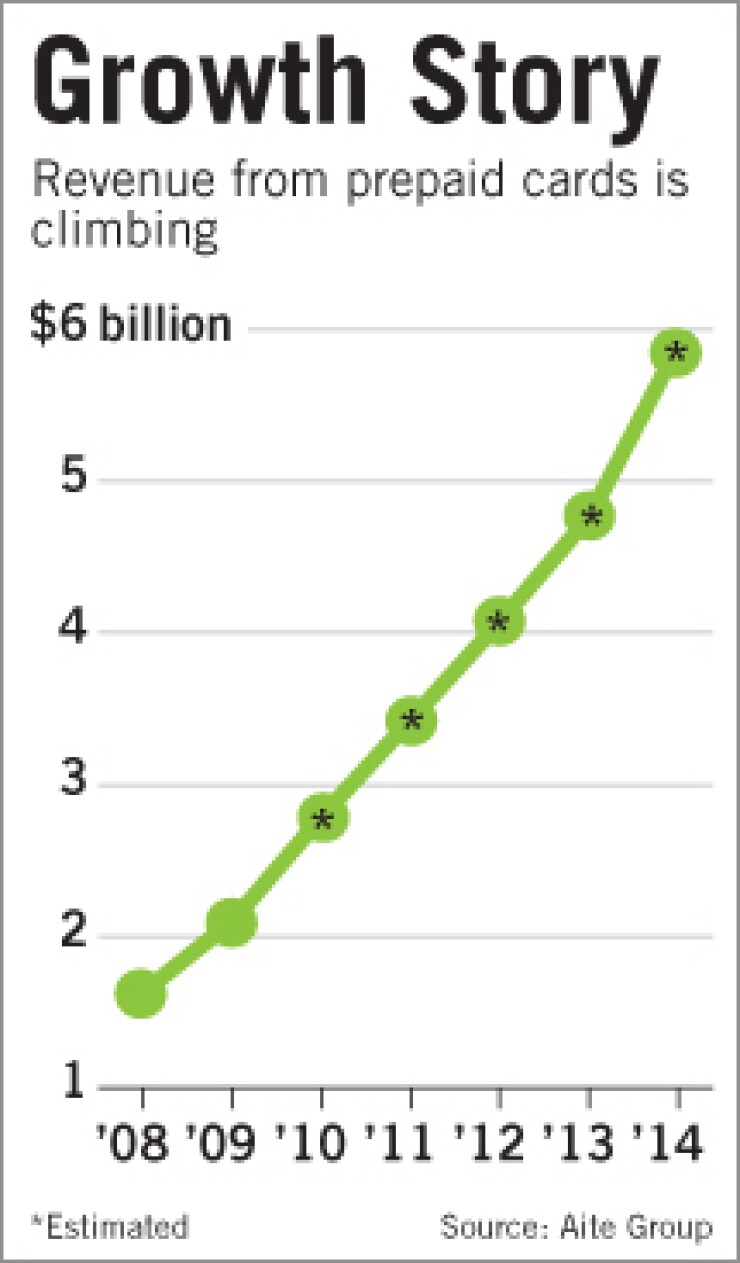

Consumers and businesses are expected to load as much as $186 billion onto prepaid cards in 2014, according to a report released last week, but uncertainty about future government regulations could hamper sustained market growth.

March 12 -

On Friday Green Dot announced plans for an IPO that could raise as much as $150 million, a move that could possibly position the prepaid card company for acquisitions.

February 26 -

Green Dot Corp. has struck a deal with U.S. Bancorp's MoneyPass Network giving its prepaid cardholders free access to the nationwide network of automated teller machines.

December 10 -

People who store money on Green Dot Corp. prepaid cards can now transfer those funds to PayPal Inc. accounts.

October 7

Green Dot Corp.'s plan to go public and buy a depository could eventually transform the prepaid card specialist into a full-fledged banking company.

In the near term, its deal for Bonneville Bancorp of Provo, Utah, would end Green Dot's dependence on the bank partners that issue the Monrovia, Calif., company's prepaid cards.

Over time, Bonneville's charter may help Green Dot retain customers who are ready to graduate from prepaid cards — a product aimed at underbanked consumers — to mainstream bank accounts.

"It certainly allows them to have a ladder of products that start with the underbanked but go right up to the banked consumer," said John Grund, a partner with First Annapolis Consulting in Linthicum, Md.

At a time when regulations threaten to pinch profit margins in the prepaid industry, Green Dot would "control more of their own destiny," Grund said.

Last month Green Dot announced its plan to raise $150 million through an initial public offering.

Earlier that month it disclosed its deal to buy Bonneville and its sole subsidiary, the $34.1 million-asset, single-branch Bonneville Bank, for $15.65 million.

Like other nonbank prepaid companies, Green Dot must strike partnerships with banks to issue its cards. In the short term, owning a bank would let it cut costs by issuing cards itself, Grund said.

Green Dot could further improve its cost structure by taking on its own processing — possibly with technology acquired through an acquisition funded with proceeds from the IPO, a option it mentioned in the IPO prospectus.

And upgrading its prepaid cards to include features such as a built-in savings account, which Green Dot also mentioned as a possibility in its filing, would put the company on the path to selling traditional banking products.

The strategy lets it take a "holistic view" of its customers and "bridge that gap between prepaid and conventional or traditional banking, but do it in way that … is consistent with their value proposition," Grund said.

Green Dot's founder and chief executive officer, Steven Streit declined to discuss its plans, citing a quiet period related to the planned stock offering.

But Green Dot's Feb. 4 application with the Federal Reserve to purchase Bonneville provides some details about how it might leverage the bank's charter.

If the acquisition is approved, Green Dot would test the savings-account feature with its prepaid cardholders, starting in the fourth quarter.

Green Dot said it would continue to meet Bonneville's Community Reinvestment Act targets for generating business in low-income markets. It said that its prepaid products, which target underbanked consumers, could help fulfill that mission by increasing access to "financial services for low- and moderate-income consumers."

In its Feb. 26 registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission to offer stock, Green Dot said that buying Bonneville would "increase the efficiency" of rolling out new products, cut the sponsorship and service fees it pays to its third parties and reduce its exposure to potentially negative changes that could be imposed by its issuing partners.

On the surface, Green Dot's strategy makes sense if its plan is to offer a wider breadth of services, said Terry McEvoy, a bank analyst in Portland, Maine, with Oppenheimer & Co. Inc.

"I can see on paper why that would be viewed as attractive," McEvoy said. "You can't sell a savings account at the cash register while you're waiting in line to buy a gallon of milk and the newspaper."

Still, building the level of trust necessary to entice underbanked consumers — prepaid card companies' main target market — to enlist in more traditional bank products could be tough, "especially in light of what's gone on in the financial services industry in the last two years and the constant news of bank failures," he said.

Green Dot, founded in 1999, has become one of the most ubiquitous prepaid card marketers in the country thanks to its massive retail distribution network.

Its cards are sold at about 50,000 U.S. retail locations, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc., 7-Eleven Inc., Walgreen Co. and Radio Shack Corp. stores.

As of Oct. 31 there were more than 2.4 million active Green Dot cards in circulation. (Green Dot defines an active card as one the use to make a purchase, reload or make an automated teller machine transaction in the last 90 days.)

Shelf life is a big challenge for prepaid companies. Consumers often spend all the money on a card, toss it and buy another one, possibly from a different vendor. The companies want to find ways to get people to keep and reuse their cards.

Like many prepaid card providers, Green Dot has addressed the problem by lowering its fees for purchasing, using and reloading its cards.

Green Dot generated operating revenue of $234.8 million in fiscal 2009, a 40% increase from a year earlier, according to its SEC filing.

Other prepaid card companies have toyed with the bank-acquisition strategy.

NetSpend Corp., among Green Dot's largest competitors, considered that route but opted to "build a much stronger relationship" with its existing card issuers instead, according to its CEO Daniel Henry.

In January, NetSpend bought a 4.9% stake in one of its issuers, MetaBank, a subsidiary of the Sioux Falls, S.D., bank holding company Meta Financial Group Inc.

The Austin prepaid company, whose cards are sold at 43,000 U.S. retail locations and can be reloaded at 90,000 locations, decided to let its issuers "focus on the … official banking side of things," Henry said.

"If I can get what I need from a great partner bank … without having to go out and get a bank charter … then we're not distracted having to become banking experts," he added.

Capital One Financial Corp. had planned to buy NetSpend in 2007 for $700 million but instead took a minority stake in the company.

NetSpend, through its issuers, already offers savings accounts that pay 5%.

Henry did not rule out doing an IPO as a potential growth strategy. "I think everything is possible," he said. "At the end of the day we've got investors who are looking at us to maximize their returns."

If Green Dot is successful at acquiring Bonneville, it could benefit financially by bringing payment processing in-house, said Terence Roche, a partner with Cornerstone Advisors Inc. in Scottsdale, Ariz. "When you get a bank, you get the BIN" — a bank identification number — "so from a processing standpoint you might have an advantage there rather than having to outsource to third parties," Roche said.

Green Dot's going public also will give insight into an industry that has been relatively guarded.

"It will really open up the kimono on a lot of the details in the business that many analysts draw conclusions on but is always nice to see in black and white," said Brian Riley, research director with TowerGroup in Needham, Mass.