-

New York state's banking regulator reached an agreement with Société Générale to retain records from an online messaging service and issued guidance for other banks in its jurisdiction that plan to use the messaging service.

October 13 -

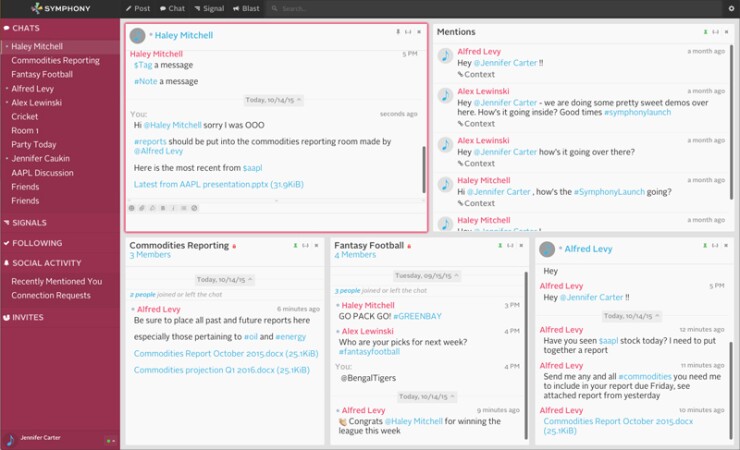

Symphony, the instant messaging service supported by fifteen large banks, says it will be ready to roll on Sept. 15 despite the objections of Sen. Elizabeth Warren and regulators who fear its encryption technology will impede supervision.

September 1 -

New York State's interim bank superintendent is asking pointed questions of a new instant messaging service. The outcome of the inquiry could broadly affect the way vendors work with regulators.

July 22 -

With New York's framework for regulating digital currency now final, a looming question is whether other states such as California will follow suit.

June 3

Who's going to get the job of holding the keys, and how can regulators seize them when there's a problem to investigate?

Furthermore, is it such a good idea to create the role of keymaster anyway?

Those are some of the outstanding questions about the new regulatory framework issued on Wednesday, by the New York State Department of Financial Services, to govern the retention of messages sent using the new platform developed by Symphony Communications Services.

The keys at issue are the decryption keys used to provide access to encrypted messages sent among banks.

The new guidelines were issued by the department on Wednesday, in tandem with a new agreement reached with Société Générale. The French bank became the fifth bank to agree to the department's rules on Symphony usage.

Additionally, NYDFS Acting Superintendent Anthony Albanese recommended that other bank regulatory agencies adopt its framework. The rules only apply to New York-chartered institutions.

The department will require Symphony to retain a copy of all its service's communications, either to or from regulated institutions, for seven years. That will give the agency a backlog of communications for certain situations, such as when a whistle-blower tips off illegal activity.

Banks must also hire an independent custodian to retain a duplicate copy of the decryption keys for their communications on the service

The second rule could cause problems for law enforcement officials, since they won't be able to go straight to the vendor, as they do now with other messaging-service providers, said David Weiss, a senior analyst at Aite Group.

"It makes criminal proceedings so painful," Weiss said. "Law enforcement officials have the same problems with iPhones and Android devices."

But other analysts believe the rule could be an improved way of dealing with this information.

"If the industry and the regulators agree that a third party should hold the encryption key, then regulators can rest assured that they won't be deprived data that they are entitled to," said Thomas Sporkin, a partner at BuckleySandler and a former enforcement official with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

"With this approach, everyone benefits," Sporkin said.

Bloomberg's Instant Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters' Eikon Messenger both compete with Symphony's messaging service. Unlike the Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters products, Symphony encrypts its data in such a way that it cannot be altered.

How a regulator accesses information, in the event of an investigation that involves the use of the Symphony service, will depend on the circumstances, said Matthew Anderson, the New York regulator's deputy superintendent for public affairs. The regulator can either issue a subpoena, or use its general power over regulated institutions, he said.

A Symphony spokesperson noted that its own security features allow banks to maintain compliance, because banks can archive their employees' communications by controlling their keys at an organizational level, a company spokeswoman told American Banker.

David Gurle, chief executive of Symphony,

In choosing the custodian, banks must consult with department officials and report its final selection to the agency.

The seven-year retention rule will provide an adequate history to support investigations, Anderson said.

"As a regulator, we want to make sure we can still uncover and identify wrongdoing when it happens," Anderson noted. "That might ultimately be many years after the fact."

The agency believes the rules will give it the legal power needed to pursue investigations, Anderson said.

"We thought given our experience in our Wall Street investigations, where these chat and other messages have been so critical to uncovering wrongdoing, that it's important to make sure that they're preserved," he said.

As for the question of whether other bank regulators will adopt the New York guidelines, Sporkin said the agency should be commended for taking a lead role and other agencies probably should follow its lead.

"You see them as the first responder here," Sporkin said.

Other regulators, however, may attempt to first test the waters with Symphony before diving headfirst into creating their own regulations for online messaging.

"If, over time, regulators feel like they're not getting what they're entitled to, then the next response is likely going to be a rule specifying the data capture, maintenance and production obligations," Sporkin said.

It's questionable whether the department would have this type of authority over the Symphony messaging service, if it weren't for the fact banks are involved, Weiss said. After all, Symphony itself is nothing but a technology application.

"DFS has no more purview over Symphony than they do over Snapchat," he said.

But banks' involvement invokes the powers given to the department through New York state's Martin Act, which gives regulators greater authority to fight financial fraud, Weiss said.