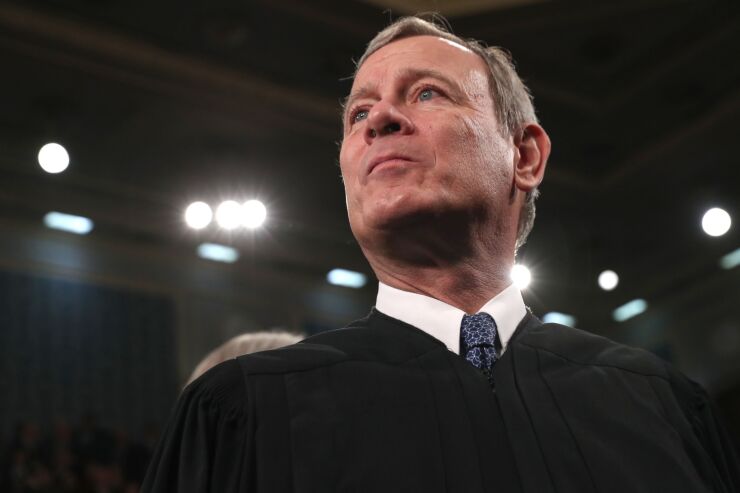

WASHINGTON — When lawyers come before the Supreme Court Tuesday to argue a pivotal case about the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, many eyes and ears will likely be on Chief Justice John Roberts.

Already seen as the swing vote on the conservative court, Roberts could hold the key to how far the court will go in providing a check on the CFPB's power, several observers say.

Some have speculated he agrees with the Trump administration that the president should have more authority to fire a sitting CFPB director, undercutting a key provision of the Dodd-Frank Act. But experts also say he is unlikely to favor the more dramatic step of invalidating the whole agency.

“There are two things about Roberts’ jurisprudence in this area that are in tension with each other,” said Jonathan Adler, a law professor at Case Western University School of Law. “On the one hand, Roberts does have a fairly formalist view of executive power. But at the same time he’s a minimalist, a justice that likes to have decisions that do not disturb the status quo.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh is viewed as the judge most familiar with the issue, having ruled twice already as a lower-court judge that the CFPB's structure is unconstitutional. But since Roberts has at times voted with the liberal minority, swinging key decisions, his opinion in the case could signal the court's direction as a whole.

"Roberts could shift majorities," said Andy Hessick, a law professor and associate dean at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

The case has drawn intense interest because of the questions it raises about executive power.

Dodd-Frank says the single head of the CFPB can only be removed for cause — definied as “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office." But critics say that afforded CFPB directors too much power, violating the Constitution and infringing on the president's power.

If the court strikes that provision, presidents would have greater leeway to fire a CFPB director from a different political party. That would allow a new Democratic president, should he or she be elected in November, to fire current Director Kathy Kraninger.

But a deeper question is whether that “for cause” provision can be easily severed from the Dodd-Frank statute, or whether striking it weakens or eliminates the agency's mandate as a whole.

Handicapping the outcome is tough because the court has weighed in on only a few cases regarding the president’s removal powers.

Roberts has in the past agreed to limit the president’s removal authority. Yet many expect the chief justice will keep the CFPB intact even while siding with the Trump administration in striking the “for cause” section.

"It’s a really hard case to predict what is going to happen because the Constitution doesn’t mention removal and we have very few precedents and nothing that deals with this particular situation,” Hessick said. “As for Roberts, there is some indication that he thinks agencies have too much power. But on the other hand, he’s not one to want to mess up massive government structures. He’s not a major boat-rocker.”

Although House Republicans, some bank trade groups and conservative critics of the agency have urged the court to completely invalidate the CFPB, most experts think it unlikely that Roberts would be willing to dismantle nine years of rulemakings, decisions and enforcement actions.

“Roberts will not go further than severing the for-cause provision,” said Vaishali Rao, a partner at Hinshaw & Culbertson and a former Illinois assistant attorney general.

Indeed, Kavanaugh too has not gone further. In past decisions, his remedy was simply to strike the for-cause provision and do nothing more.

Kavanaugh wrote a scathing 101-page opinion in a 2018 case, PHH Corp. v. CFPB, when he was on a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. That panel ruled that the "for cause" protection for a CFPB head — who runs an agency with funding directly from the Federal Reserve and and which is not governed by a board or commission — violates Title II of the constitution.

Yet that decision was overturned by a ruling from the full appeals court that

Many expect the court hearing Tuesday to include a broader discussion about the authority granted to independent agencies.

“The real action" in oral arguments "is going to be about to what extent the majority of the court is convinced that the CFPB is more independent and a greater deviation from the traditional power given to independent agencies,” Adler of Case Western said.

Kavanaugh had written that the advent of independent regulatory agencies poses a threat to individual liberty unless an agency's powers are checked. Yet Kavanaugh also supported the remedy of simply striking the for-cause provision while honoring Dodd-Frank's "severability clause" that states if one provision of the act is found to be unconstitutional, the rest of the statute would still remain.

Past cases suggest Roberts may agree that the court should not upend the entire law.

"Chief Justice Roberts has made clear in a bunch of cases his preference to strike down as little of a statute as is necessary," Adler said. "He tends to not like broad disruptive judgments, even though in separation of powers cases we see him guided by a fairly conservative understanding of the nature of executive power."

Roberts also is known for siding with the liberal minority in decisions that have surprised court watchers. In a notable example, he helped to uphold the individual mandate to buy health insurance.

"Roberts is skeptical of administrative power but appears realistic about balancing Congress’ authority," said Christopher Peterson, a law professor at the University of Utah College of Law and former senior adviser at the CFPB. "If Roberts swings to Kavanaugh’s side, and a majority say the 'for cause' removal provision is unconstitutional, they are going to have to have an explanation for why that provision is severable from the statute."

Hessick agreed with others that Roberts may favor a similar approach as Kavanaugh. He said there is also a chance that the case results in a split majority opinion, where a majority agrees that the for-cause provision is unconstitutional, but Roberts sides with the four liberal justices in determining the provision is severable.

Yet the Supreme Court could issue such a ruling and still call on Congress to improve the structure of the CFPB further.

“I can see Roberts saying, 'Let’s just strip out the for-cause removal provision, we’ll just excise that provision with a scalpel, because it does the least damage and placates all the relevant constituencies on the conservative side,' " Hessick said. "I think severability is where the true fight is going to come down with the conservatives — do they want to strike the whole bureau or just that provision?"