BB&T’s megamerger with SunTrust Banks could spark interest in forming new banks.

Groups eager to form de novos could find talent by recruiting bankers displaced or disenchanted by the

A more accommodating regulatory environment could provide more incentive. Organizers in markets such as Atlanta; Charlotte, N.C.; and Richmond, Va.; where the regional powers have considerable overlap, could benefit the most.

Market presidents or city executives from BB&T or SunTrust would be the most likely candidates to start new banks, said Lee Bradley, senior managing director at Community Capital Advisors in Duluth, Ga. Those bankers typically have the managerial experience and community connections necessary for leading a new bank.

“I could see some of those folks coming up with the idea of going de novo and swiping up some of their [current] customer base,” Bradley said.

Big bank mergers were a catalyst for de novo activity before the financial crisis, said Jeffery Smith, a lawyer at Vorys, Sater, Seymour & Pease.

Some bankers may use the BB&T-SunTrust combination as a chance to reflect on whether they want to move to a smaller institution where they can have a greater impact and closer contact with clients, Smith said. Others could determine that they want to start a bank to help local communities.

“The types of bankers that de novos tend to attract ... have an entrepreneurial streak and that's often not the environment they find themselves in in a larger institution,” Smith said. “I would certainly imagine that the BB&T-SunTrust merger would result in bankers looking at opportunities in smaller institutions in their markets, as well as potential de novo opportunities.”

Bankers who come from larger institutions may have a strong client base, which would provide a startup with "instantaneous business,” Smith said.

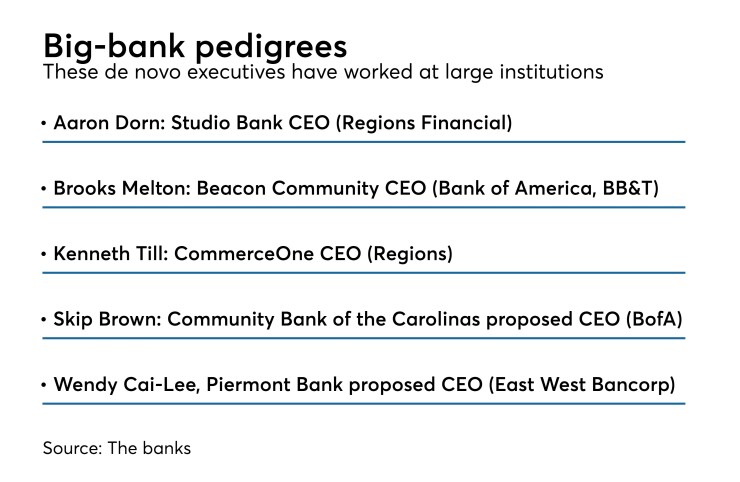

A number of bankers who have opened banks, or are looking to form banks, have experience at larger institutions.

The group behind Piermont Bank in New York has several organizers from the $41 billion-asset East West Bancorp in Pasadena, Calif., including Wendy Cai-Lee, the bank's proposed president and CEO. The group, which has been working quietly for months since receiving FDIC approval in early December, needs to raise $100 million before it can open.

Skip Brown, the proposed CEO of Community Bank of the Carolinas in Winston-Salem, N.C., was a market executive at Bank of America when he left in 2004 to form TriStone Community Bank. TriStone sold to First Community Bancshares in Bluefield, Va., in 2009.

Aaron Dorn, president and CEO of Studio Bank in Nashville, Tenn., spent three years at Regions Financial early in his career before moving to a community bank.

Kenneth Till, CEO of CommerceOne Bank in Birmingham, Ala., spent 16 years at Regions. He was also chief financial officer of the $267 million-asset First Partners Bank when it was sold to Progress Bank in 2017.

To be sure, things have changed since the crisis. Many executives who formed banks a decade ago grew frustrated by the multifaceted responsibilities and challenges that arose after the crisis ended, industry observers said.

“Prior to the end of the last de novo wave, we saw a number of bankers coming out of large banks start or attempt to start de novos,” said Jonathan Hightower, a lawyer at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner.

“In a new business, management is responsible for everything from managing a new board and shareholder base to ensuring there are a sufficient number of pens in the lobby,” Hightower said. “It became obvious for many of them, sometimes too late, that they had underestimated the insulation from day-to-day administrative burdens offered by large organizations.”