If the White House makes good on its promise to support $1 trillion in new infrastructure, it may do so without the onetime kings of the business: big U.S. banks.

The most prominent names in banking — Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America — have significantly pulled back from infrastructure lending in recent years while foreign competitors filled the void.

The story of how U.S. banks ended up in the back seat of a market on the brink of a possible boom highlights one of the far-reaching effects of post-crisis regulations. The adoption of more stringent capital standards has made the business of providing long-term loans for power plants, toll roads and telecommunications systems too expensive, according to attorneys, academics and former executives in the field. Whether banks can get back in the game in the coming years — or even want to — is a matter of debate.

“A combination of the financial crisis and the deleveraging of banks … just made it more difficult for U.S. banks to make these types of long-term loans,” said Michael Bennon, managing director for the Global Projects Center at Stanford University.

Bank loans, Bennon said, have historically been a key component of public-private partnerships — a

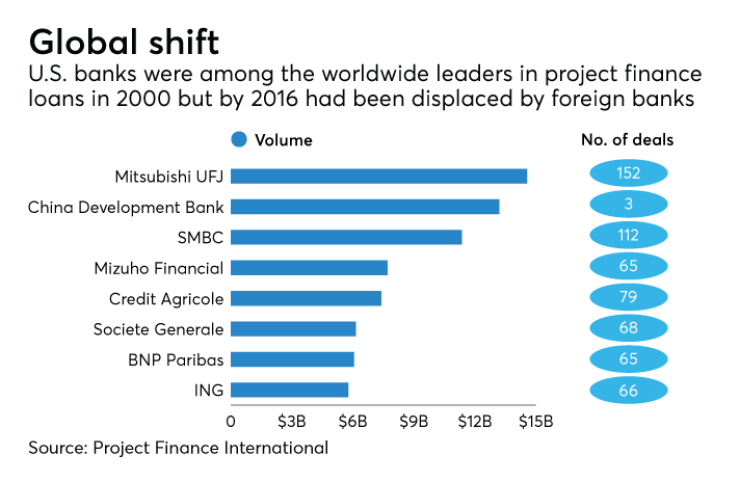

Last year, Japanese banks including Mitsubishi UFJ and Mizuho Financial were among the global leaders in project-finance lending, arranging $14.4 billion and $7.7 billion in loans, respectively. By contrast, back in 2000, big U.S. banks occupied three of the top spots on the list.

Rules such as the

As far back as the mid-2000s, Basel regulators began debating whether project-finance lenders should be subject to tougher capital standards, according to Robert Dewing, a retired banker from JPMorgan and Citigroup who now teaches infrastructure finance at Columbia University. Banks, in turn, began to withdraw.

“American banks are very well regulated, so they have pulled out of that long-term market,” Dewing said. “They do make some long-term loans, but it’s a small proportion of what they used to make before Basel II and Basel III came along.”

Japanese banks, in contrast, have “an affinity” for longer-term lending, as well as regulators who look more kindly on the business, according to Dewing.

“As other people have dropped away, [Japanese banks] have capitalized on that,” he said.

The global shift in infrastructure lending in recent years has happened in the backdrop of a closely followed push in Washington to revamp the nation’s highways, waterways and airports.

Over

On June 5, President Trump proposed partially privatizing the nation’s air traffic control system. Later in the week, he outlined in broad strokes a plan to spend $200 billion in a variety of sectors over the next decade. Such a plan could include incentives for as much

On the campaign trail, the president promised to rebuild the nation’s crumbling infrastructure — such as wastewater treatment plants, railways and state-funded schools — that have languished for years without much-needed upgrades.

The American Society of Civil Engineers has estimated that at least $2 trillion in funding is needed to improve the nation’s infrastructure.

“I think it’s quite possible that the administration will have to lead the effort” to move a bill through Congress, said Marcia Hale, president of the Building America’s Future Educational Fund and a former official in the Clinton administration.

“There is a deal to be made,” Hale added, acknowledging that the prospect of success becomes less likely as Congress is distracted by other issues.

It remains to be seen how the White House’s infrastructure push will play out in the months ahead and what kinds of incentives it will include for private capital.

Commercial project lending, of course, is just small sliver of the complex web of infrastructure finance. Most big projects largely rely on tax-exempt municipal bonds.

Banks arrange commercial financing in other ways beside making loans, including by managing the issuance of project bonds. During 2016, global issuance totaled $43.6 billion — less than a quarter of the size of project-loan market, according to Project Finance International.

Citigroup and JPMorgan, for instance, were among the companies that managed a 2016 issuance for

Additionally, big banks also act as intermediaries, helping large pension funds and asset managers — increasingly powerful players in the market — invest in bonds and long-term infrastructure loans. Those institutional investors have become so adept and independent in identifying assets that they could cut banks out of the picture.

Banks “are going to find it harder and harder over time because the pension plans and insurance companies, as they become more experienced and their portfolios grow, will become principals in their own right in the market, and they won’t need commercial banks to be intermediaries,” Dewing said.

He noted that firms such as MetLife and Prudential have big teams tasked with infrastructure investing that are increasingly competing with commercial banks.

Still, some observers say big U.S. banks may have an appetite to regain their edge in the once-profitable project-lending business.

“I think they’d like to — it’s a business they’ve been well compensated for, particularly for construction,” said J. Paul Forrester, a partner who focuses on infrastructure and energy financing at the law firm Mayer Brown.

For project sponsors, loans provide the type of flexibility that’s needed to handle unexpected scheduling delays and other interruptions.

To fill the void left by U.S. banks, sponsors have increasingly turned to government loan programs, according to Bennon. In particular, direct loans offered under the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program, or TIFIA, have been a popular option.

Getting back into the project-lending business, however, would require banks to structure project loans in a way that includes shorter terms of between five and 10 years with an incentive to refinance at the end.

U.S. banks contacted for this story — JPMorgan, Bank of America and Citigroup — did not respond to a request for comment by deadline. Mizuho and the U.S. subsidiary of Mitsubishi UFJ also did not respond.

As policymakers examine ways to revamp the nation’s infrastructure, they will likely look first for the best “quick hits,” according to Dewing.

He pointed to President Trump’s proposal in the past week to partially privatize air traffic control. Other possibilities include raising public capital to revitalize facilities at public universities.

Given the expertise that U.S. banks have developed in analyzing public-private infrastructure projects, they will continue to have an important seat at the table when it comes to advising federal, state and city governments, observers said. Their ultimate role could be as lead financial advisers for hire.

“There’s an opportunity there because they are global, and they do understand best practices in a number of jurisdictions — they can be sources of good leadership,” Dewing said. “But I don’t think they are going to be the providers of the capital, as principals, anytime soon.”