Consider a scenario in which greenhouse gas emissions are left unchecked, and sea levels rise by two feet over the next five to 30 years.

Under that hypothetical, Regions Financial forecasts a moderate long-term risk to its consumer and commercial real estate loan portfolios. The company is taking several actions now to prepare for that possibility, such as trying out new risk models, enhancing geospatial data and monitoring the severity and frequency of serious weather events.

The scenario analysis is part of a report the Birmingham, Alabama, company issued in June, following a framework laid out by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Over 24 pages, Regions described its strategy for addressing climate risk, established targets that it wants to hit in the short term, and outlined some of the business opportunities it sees in the green economy.

The report could be something of a bellwether for small and midsize banks. The big Wall Street banks have published similar reports, but the $156 billion-asset Regions has scant company among banks its size or smaller.

Some observers believe that will change as regulators and shareholders demand greater detail into how banks’ portfolios could be affected by a warming world or an abrupt shift away from fossil fuels. Climate risk disclosures are not currently required of any U.S. banks, but the Securities and Exchange Commission is considering a proposal to require that public companies disclose their climate risks.

For Regions, the climate risk disclosure report was “the logical next step” in its environmental, social and governance program, said Chief Governance Officer Andrew Nix.

“The stakeholder pressure is there, the movement is there, there are parties who are going to remain interested for their own purposes, but it’s way better to feel like we’re ahead of that, doing it for our own purposes and not just reacting,” Nix said. “This is all fast developing from a regulatory standpoint. I think we may begin to see more expectations from our banking regulators, certainly as a public company.”

The Financial Stability Board, which makes recommendations on the global financial system, established the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures in 2015 under its then chair and Bank of England Gov. Mark Carney. Initially led by the billionaire Michael Bloomberg, the task force was founded to develop a set of voluntary disclosures around climate-related financial risks.

The task force’s framework has now become the de facto standard for banks reporting climate-related risks on a voluntary basis. JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America and Wells Fargo have all published reports. The Bank of England, which will require the firms under its supervision to report their own climate risks, published its own report in June.

Different banks are using the reporting framework differently, said Dan Saccardi, senior director at Ceres, a nonprofit organization focused on corporate sustainability. Some have used it to aggregate information that might easily be found from other sources, while others have begun to incorporate brand-new information and scenario analyses.

“Regions has frankly done some good work here, particularly given that it’s not one of the global banks,” Saccardi said. “They are looking at both physical risk and transition risk, and beginning to do some analysis of the impact on their business.”

While the industry as a whole is still fairly new to reporting financial risks from climate change, smaller financial institutions could be especially challenged to gather and analyze the data they need to disclose the necessary level of detail.

Regional and smaller organizations are not doing anything fundamentally different than larger firms, but they do often need much more granular, local information, said Alexandra Mihailescu Cichon, executive vice president at RepRisk, a data science firm specializing in ESG risk. That could mean, for example, aggregating local news sources or enlisting experts who may be more familiar with local companies and issues.

“That has proven to be a challenge for many organizations,” she said.

Banks may already have a lot of the data they need to assess climate risks in their portfolios, but they may not have it captured and aggregated in a way that makes it easy to analyze, said Emilie Mazzacurati, founder and CEO of Four Twenty Seven, a Moody’s affiliate focused on climate risk.

“That’s one of the main challenges for banks: They need to develop a clear data strategy and model for capturing internal and external data sources they need,” Mazzacurati said. “It may exist in the systems, but it could be very fragmented.”

Compiling the Regions report took about a year, according to Nix, who said that the work began before he joined the bank in March 2020. It involved bringing together many different functions across the company — including risk, legal, facilities and procurement, and corporate banking — to get a holistic picture of where the biggest risks and opportunities lie, he said.

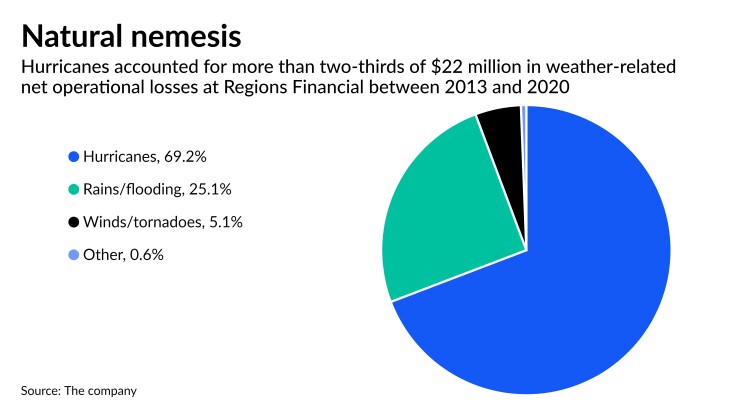

In one example of the detailed work that went into the report, Regions calculated its operational losses from weather-related events between 2013 and 2020. Regions has a large footprint in the Southeast, and some 69% of the net weather-related operational losses came from hurricanes, while another 25% were related to rains and flooding.

Nix emphasized that the report is not a sign that Regions is moving away from financing any particular industries, and said that the bank intends to work with its corporate clients on their own climate plans.

Regions intends to issue this report on an annual basis, and it has identified particular sections that it intends to expand in future versions. For example, it will define what “sustainable finance” means for its organization, and it plans to start reporting on so-called Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions, or those emissions that it may be indirectly responsible for, such as through its financing activities.

Some banks may see advantages in assembling a climate risk report now, before their regulators ask for one. Saccardi said he has had conversations with other large regional banks that intend to publish such reports in the near future. Banks that act sooner will be in a better position if and when regulators do require those disclosures, he said.

Banks may have other reasons for undertaking the effort, though. Some may see it as a way to provide additional value for corporate clients thinking about their environmental efforts, for example. Others may simply want to get a better handle on the risks facing their own organizations.

River City Bank in Sacramento, California, recently formed an internal climate change committee. That group has begun to undertake a climate risk assessment of the bank’s portfolio, and is looking at what it might need to put together a climate risk report, though it has not firmly committed to taking that route.

As a $3.4 billion-asset firm that is not publicly held, River City Bank would not be required to make disclosures under the SEC’s proposal. But it sees value in climate risk modeling as an additional component of stress testing, said Rosa Cucicea, director of the bank’s clean energy division.

“One of the benefits of getting ahead of it is showing that you’re actually doing this because it’s important to you as an organization or your customer base,” Cucicea said.