-

An estimated 12 million Americans buy used cars through informal channels each year. Those consumers are underserved by traditional auto lenders, says Lending Club Chief Executive Renaud Laplanche.

August 3 -

Tech investors love fast-growing marketplace lenders like Social Finance, but Wall Street has taken a dimmer view of them. A huge equity fundraising round should allow SoFi to keep fueling rapid growth while remaining privately owned.

August 20 -

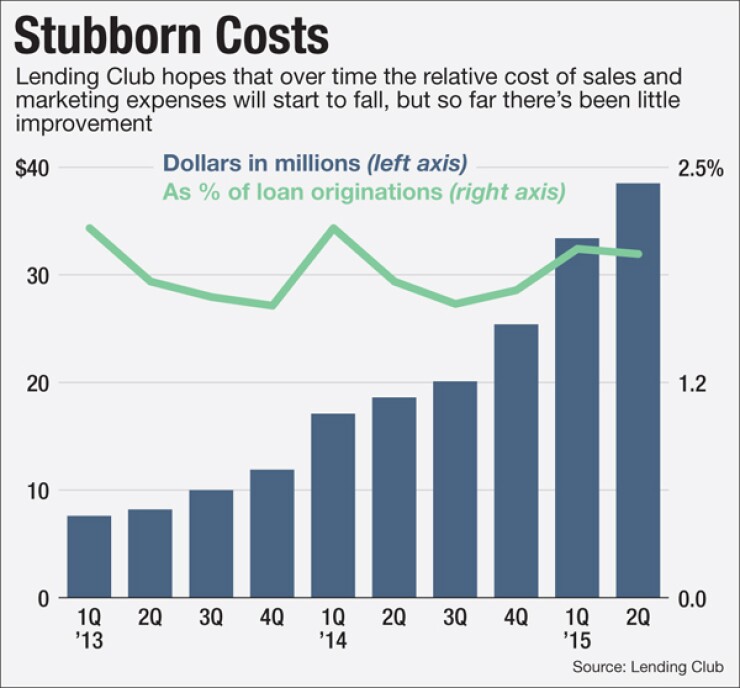

Companies like OnDeck and Lending Club are under pressure to keep finding new borrowers, but there are signs that customer acquisition costs are rising amid heavier competition.

May 6 -

Lending Club reported a small quarterly loss on Tuesday as the marketplace lender stuck with its strategy of pursuing growth rather than near-term profitability.

August 4

SAN FRANCISCO — It takes some chutzpah to build a call center in one of the nation's most expensive real estate markets.

That is what Lending Club has done in downtown San Francisco, locating its operational hub inside a modern high-rise that fittingly straddles the city's financial district and an adjacent neighborhood that is home to many technology startups.

When a Lending Club borrower calls the company's customer-service line, the folks who answer the phones are largely young college graduates. Their well-lit, high-ceilinged office space bears no resemblance to the drab cubicles that are typical of the call center industry.

And like their better-paid Lending Club co-workers, these employees enjoy lavish job perks, including a nine-hole mini-golf course and a company-run tavern that opens at 5 each evening.

Lending Club is not the first consumer finance company to

[Coming this November:

Hundreds of employees who work in customer service, fraud detection, credit decisions and collections all sit under the same roof as Lending Club's engineering staff. The firm, which had a total of 1,136 workers as of June 30, fosters frequent communication about which processes are working well and which are not.

"The co-location of operations and product and engineering is really important for that feedback loop to be as tight as possible," Lending Club Chief Executive Renaud Laplanche said in an interview. "What we're trying to achieve is really using technology to lower costs and deliver a better experience to our customers."

The approach at Lending Club is emblematic of the new breed of financial companies. These firms do not have sprawling branch networks, which are costly but still provide some key advantages for incumbents. The newcomers believe they will prevail because they have better technology, and they are deploying it from the ground up.

As Laplanche

The question is: will the strategy work?

BUILDING A BRAND

Lending Club, which went public late in 2014, has had a rough summer. In June the firm's shares dipped for the first time below Lending Club's initial public offering price of $15. Since then, they have fallen below $13, or less than half their peak in December.

Some of the decline is likely due to early-stage investors cashing out after restrictions on their ability to sell stock were lifted. (Laplanche bucked that trend

But investors also have raised concerns about Lending Club's business model. One worry involves

Another nagging concern involves Lending Club's customer-acquisition costs, which remain significantly higher than those of better established lenders.

In May 2014, Lending Club

One challenge facing the entire marketplace lending sector is that borrowers are just not very familiar with its brands. Companies like Lending Club, Social Finance and Prosper Marketplace do not have long track records. Nor do they have retail storefronts to provide advertising and to serve as a symbol of trust.

Consequently, each dollar that these firms spend on marketing will probably have less impact than a dollar spent by a well-established credit-card issuer, according to Matthew Lipton, an analyst at Autonomous Research.

Lending Club, which

When Laplanche was asked about his timeline for establishing Lending Club's brand, he replied that the process took 120 years at JPMorgan Chase. Then he laughed and added: "Our goal is to do it faster. How quickly we're going to get there, it's really hard to say."

"I think over time, our brand is becoming more and more permanent, and more well known. I think our IPO was useful from that standpoint," Laplanche said. "As the brand gets more prominent, we're certainly seeing marketing efficiency getting better, and our acquisition costs coming down as a result."

But there is fierce competition for the personal loan borrowers that are the bread and butter of Lending Club's business. One way the company finds customers is by paying referral fees to Lending Tree, the comparison-shopping site, where 22 other firms are also competing for personal loan business.

Earlier this month Lending Tree

Competition is particularly intense for personal loan borrowers with strong credit scores, a cohort that makes up a big part of Lending Club's customer base, according to Alex Johnson, a senior analyst at Mercator Advisory Group.

"It's harder to catch the attention of those borrowers because they tend to have more options," he said.

DRIVE FOR EFFICIENCY

Inside Lending Club's call center, productivity gets measured in many ways. The metrics that are tracked include the number of calls coming in, how long callers are waiting, and how long it takes for a company representative to answer a ringing phone.

Not only do these numbers give the company a way to measure its overall customer-service performance. They are also used to encourage employees to compete against each other. Whiteboards tracking the standings hang from the wall near each small team of employees.

When call-center staffers start seeing the same question from numerous customers, they flag it for the company's engineers, who can respond quickly by making revisions to Lending Club's website.

The goal throughout the operations side of the business is to use as much automation as possible, and to minimize human intervention. In other words, the employees are expected to find ways to keep their own ranks small.

"We really rely on our operations professionals to act almost as process engineers, and to essentially sort of sit down with product and engineering very often," Laplanche said.

"They have this very tight interaction, where they can share sort of everything that has come up as a bottleneck on any single day, and have product and engineering sort of come up with a technology-enabled solution for that problem, as opposed to just throwing more people at it," he said.

Customer satisfaction is especially important at Lending Club in light of the high cost of acquiring new customers. All else being equal, the company's best customers are repeat customers, because they are cheaper to bring aboard than first-time borrowers.

In its

The firm also said that it has been getting better at attracting repeat customers. For loans made in 2009, 19% of customers returned for another loan after three years; for 2012 loans, that number was up to 30%.

In the same earnings presentation, Lending Club stated that it has zero sales and marketing costs for repeat customers. But when asked about phone calls that company representatives sometimes make to existing Lending Club customers, urging them to borrow again, the company said that those expenses are not classified as sales and marketing costs. Instead, they are counted as origination and servicing costs.

There is another benefit that Lending Club gets from happy customers. Borrowers who are satisfied are also more likely to refer friends and colleagues to the company. And even though Lending Club sometimes has paid referral fees to its existing customers, those costs are likely significantly lower than the fees it pays to acquire customers through other channels.

It is probably too early to evaluate Lending Club's counterintuitive decision to locate its operations staff in downtown San Francisco.

The company has increased its loan volume by more than 100% each year since 2009, but it is not yet profitable. At the same time, Lending Club maintains that its operating expenses are substantially lower than those of traditional lenders, even beyond the savings that result from having no branches.

"We believe the way to achieve sustainably lower costs and better experience isn't to necessarily lower the cost of the location, or lower the cost of the salary we're going to pay people, but more in using technology to implement better processes," Laplanche said.