-

With the EMV liability shift having just passed, banks and merchants alike are scrambling to comply with the card network-imposed deadline.

October 23 -

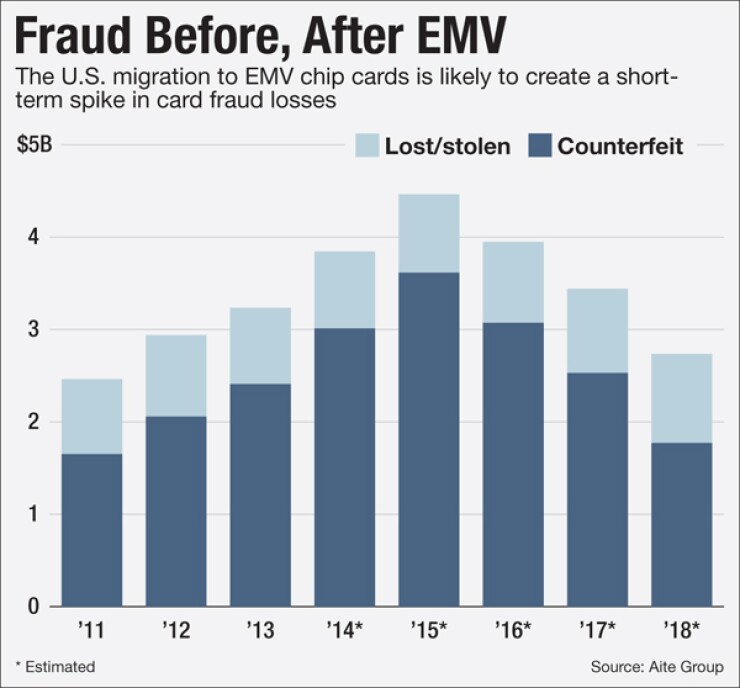

Large banks and card issuers are ready for the U.S. shift to chip-and-PIN technology, according to a report issued Wednesday. But the drop in fraud that is expected to result is unlikely to come any time soon.

March 18 -

Retailers will no longer be easy pickings for cybercriminals once chip-and-PIN technology is widely adopted. All well and good, but bankers fear hackers will redirect their energies to infiltrating banks.

December 24

A month has passed since the deadline by which the U.S. was supposed to adopt credit and debit cards with computer chips on them — a deadline everybody's known since 2011.

Many banks and retailers not only missed the Oct. 1 date without breaking a sweat, they show little sense of urgency about getting the new chip cards in consumers' hands and making them usable in stores and restaurants.

The so-called liability shift, in which merchants that can't accept chip-enabled debit and credit cards will have to eat the cost of fraud on such cards, was expected to kick the industry into action. (These cards contain an integrated circuit that stores payment information according to a specification set by Europay, MasterCard and Visa. Hence they're often called EMV cards. The silvery thing that looks a little like a computer chip on the face of the card is not the chip itself, but a protective overlay. Chips are much harder to duplicate and compromise than magnetic stripes.)

Yet today, 46% of Americans have not yet received chip cards (according to MasterCard data) and only 41% of merchants have installed the equipment and software they need to accept them (according to a survey conducted by TD Bank). As the industry drags its feet, fraudsters have already begun phishing scams that take advantage of the general confusion over EMV cards, and other types of card-related fraud are expected to increase.

Many factors have combined to slow progress: There's been a chicken-and-egg effect — card issuers didn't want to get cards out in the marketplace too early to customers who had no place to use them. Retailers feared that if they train their clerks on the new terminals, the training would quickly become stale without practice. Some smaller card issuers have preferred to let others be the first to deal with customers' questions and complaints about the new cards. And some smaller merchants have simply refused to lay out the money required to upgrade their payment terminals to accept the new cards.

"If you think about the size of the infrastructure in the U.S. …there's a lot of different players in the ecosystem and it's complicated," said Julie Pukas, head of U.S. bank card and merchant services at TD Bank. "We're talking about the biggest payment network in the world, so everything is magnified. It was just a bigger process than people anticipated."

There's some movement toward EMV adoption. At the end of October, 34% of MasterCard-branded credit and debit cards and 48% of MasterCard credit cards contained EMV chips.

In a survey MasterCard conducted in October, 54% of consumers said they had at least one chip card in their wallet. About 30% also reported that they use the chip card more often than other cards in their wallet, according to Carolyn Balfany, a senior vice president at MasterCard.

The Payments Security Task Force, an industry group, projects 60% of all cards will be chip-enabled by the end of the year, 98% by the end of 2017.

Still, you'd think those numbers would be closer to 100% by now.

"You see consumer sentiment and consumer preference for a chip-enabled product," Balfany said. "That suggests there's a competitive imperative for issuers to be putting chip cards in consumers' hands."

In September, 457,000 U.S. merchant locations were chip-enabled, according to MasterCard data. In October that number rose to 676,000, about 49% growth in a month.

Obstacles Remain

One challenge for debit card issuers has been compliance with the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act. This requires merchant acquirers to provide merchants a choice of networks for routing debit card transactions, and mandates that all debit cards support at least two unaffiliated networks. To handle the routing requirements, the card networks had to agree on a common application identifier (a string of characters that identifies the network and the type of card).

"That took time to work out and it was met with hesitation," said Balfany. "It's a whole new process … that's not been done in any other market, so it was net-new and, probably rightfully, some were cautious about what that would look like in execution."

This Durbin effect is wearing off and by January, Balfany expects to see equal numbers of credit and debit cards being reissued with embedded chips.

Some smaller card issuers made a strategic decision to not be part of the first wave — to let their customers learn about the cards from others first, said Randy Vanderhoof, director of the EMV Migration Forum, another industry group.

"The fear is that the customer support phone lines of those small issuers would be flooded with customers who didn't know what the chip card was or how it worked or why they were getting one," Vanderhoof said. "It would fall on that bank to be the primary source for customer education. Some financial institutions may have chosen to let the big retailers and big banks spend the dollars to do that level of education. Then they'd come in after that consumer has become more educated and it would be less of a strain on their support system to service those customers."

Others wanted to be ready by October but underestimated the lead times required to get card stocks ordered, processes upgraded and everything tested and certified.

Small card issuers don't seem to feel pressure to adapt.

"Ifyou're a small issuer, perhaps a community bank, you're not dealing with the same type of fraud risk the bigger issuers are," Vanderhoof said. "They may look at their fraud levels today and feel like those costs are still manageable. They may want to wait until things settle down before they start investing in new card technology."

Another cause of delay is card processors, many of whom have been tied up handling upgrades for their largest clients.

"For most institutions that have not issued cards yet, it's simply because they're waiting in the queue to get their cards or to get their processor to enable them to start issuing their cards and doing authentication, because all the resources in the market are tied up right now with the bigger dealers," said Vanderhoof.

It is a capacity issue, he said. "No one wants to invest long-term in a whole bunch of facilities and printing equipment and personalization equipment that in two or three years will be idle again," he said. "So they have to make some tough planning decisions to service their customers and meet the demand but not overinvest on the peak demand we're experiencing right now."

Overloaded processors also affect the merchant side.

"We've been waiting for various processors to develop the software that will enable those transactions," said Pukas at TD Bank. Merchants that have newer terminals may not need new equipment, they might just need to download new software, she said.

A study conducted by TD Bank found that only 41% of small businesses have obtained and installed the equipment they need to accept the new chip cards. Another 40% say they plan to, 10% don't plan to, and 9% aren't even aware they should be doing this. Among those that don't plan to upgrade, 41% say it's not a priority, 26% say it's too costly (the average cost is $450 — a burden for a small bar or dry cleaner), 13% are not concerned about fraud, 13% say the technology is confusing, and 3% say they do not have enough time.

"Merchants have largely been shielded from the cost of fraud, so they estimate it to be quite low," Vanderhoof said. "So when they look at the cost of the investment in time and the cost for the upgrade to EMV, they have a hard time justifying it."

Some of these merchants face a rude awakening when they start getting their bank statements in December, January and February.

"They might be surprised at seeing more chargeback activity than they thought they were experiencing in their store, and that will change the financial decision about whether or not this is too expensive to do," Vanderhoof. "They may accelerate that investment and get that change installed as quickly as possible."

Banks like TD are approaching their most at-risk merchants first to encourage them to adopt the EMV standard. For instance, jewelry stores sell a product that's easy for a thief to transport and resell. They're among the first retailers the bank reached out to.

The Risks

As reasonable as some of these explanations sound, they don't excuse the industry's sluggishness.

The reasons to adopt EMV are more relevant than ever: the need to reduce counterfeit, lost and stolen card fraud. According to Aite Group, counterfeit cards account for 37% of U.S. card fraud losses, and all told, fraud rates have doubled from five basis points in 2007 to 10 basis points in 2014. Fraudsters flock to this country, knowing they can still pull off schemes that are blocked throughout most of the world.

"The risks that were in the market before EMV came along are still there, getting reduced by the week, month and year as more EMV chip-on-chip transactions start to happen," Vanderhoof said. "Because we have such a large and diverse market to get the total turnover in place, the fraudsters will continue to focus on those cards that are still magnetic stripe that will be accepted in those merchant locations that can accept the chip. The fraud will not disappear until it gets to the point where those fraudsters are just running out of places where they can use their counterfeit cards."

Card criminals are already beginning to change tactics. There have been reports of fraudsters emailing or calling consumers, claiming to be from their bank and requesting account information for a new EMV card.

"That's just clever criminals taking advantage of unsavvy consumers," Vanderhoof said. "That probably has a short window because word will get out and a few people will be burned by this, then the criminals will start to look at other tactics."

Account takeover is another strategy criminals are expected to shift to, as more cards become chip cards that are hard to counterfeit. The fraudsters will apply for new cards using stolen personal information.

"There are always going to be attacks and counterattacks and strategies between what the payment industry knows are vulnerabilities and what criminals are used to getting away with," Vanderhoof said. "We're closing this big hole in the boat right now, which is counterfeit card fraud, and by managing that hole and reducing it, that now frees up issuers and merchants to focus on the other holes, card-not-present channels and online channels, which EMV doesn't address. Since everybody's heads-down on implementing EMV in the store, online fraud is continuing to rise because there aren't enough resources for all fronts."

Once EMV is fully implemented in the U.S., card fraud will be gradually squeezed out of the system, as it has been in other countries. It behooves all players in the card industry to speed up this process.

Penny Crosman is American Banker's editor at large. She welcomes feedback on her column at