To get a sense of why Ally Bank wants the Community Reinvestment Act rewritten, look at its situation in Utah.

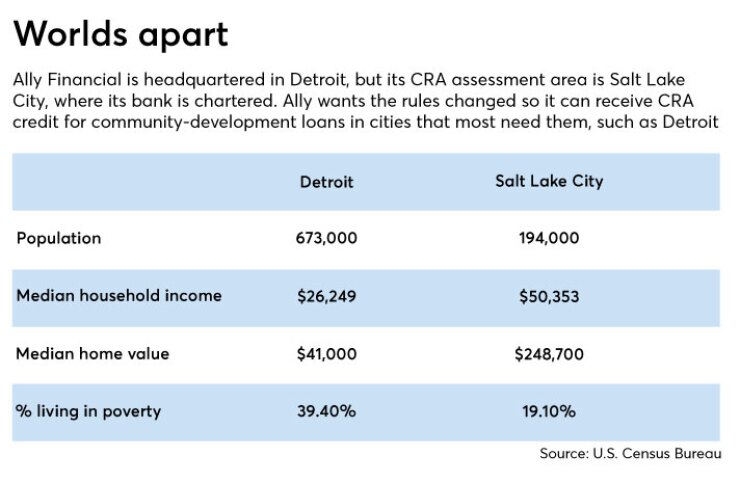

Since it has no retail branches, the $137 billion-asset Ally is assessed for CRA compliance for its lending in Salt Lake City, where its bank is headquartered. But Ally gets no CRA credit for lending in Detroit, where its holding company is based and where nearly four in 10 households are living in poverty.

The CRA, which was last updated in 1995, should be revised to reflect the business realities of online-only banks like Ally, said Jan Bergeson, its CRA compliance director.

“It’s an irony and a frustration for us that we can’t get CRA credit in Detroit, since so much is needed there” in terms of community development, Bergeson said.

Regulators are aware of Ally’s situation and other changes in the banking industry that aren’t reflected in the 41-year-old law. The Treasury Department recently

“Treasury has determined that this method of directing CRA loans, investments, and services may exclude a substantial portion of the communities that the banks are effectively serving,” the agency said in its April 3 report.

One of the main issues is how to treat online-only banks like Ally, San Antonio-based USAA or Goldman Sachs’ Marcus. Since CRA assessment is based on a bank’s geographic territory, online banks have little incentive to make loans in a specific area, even if those communities are in need, said Jesse Van Tol, the CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

“We think there should be a more robust regime for online banks,” Van Tol said.

Utah offers an example of how the CRA impacts banks with a limited, or nonexistent, retail branch network. As the headquarters of

When the geographic requirement was first implemented in 1995, there was intense competition among Utah-based banks for a limited number of CRA credits, said said George Sutton, an attorney at Jones Waldo and a former state banking commissioner. Since then, banks have convinced regulators to grant them CRA credit for lending outside the state, after they meet certain requirements in Utah, he said.

But there are still issues with meeting those minimum requirements inside Utah, said Krista Shonk, vice president of regulatory compliance at the American Bankers Association. The intense competition for CRA loans in the state creates a situation where banks sometimes lose money on these loans, she said.

“It’s an overheated market,” Shonk said.

In Ally’s recent CRA compliance exam, the bank was given credit for its lending only in Utah and some surrounding states. Though Ally received an 'outstanding' rating, it would like to see CRA credit granted in other places where it operates, Bergeson said.

Other online-only banks seek the same kind of treatment, Shonk said.

“Online-only banks want the ability to provide funding in areas that have a demonstrated need outside of the areas where their headquarters are located,” Shonk said.

The CRA could be rewritten to lessen the reliance on a bank’s headquarters city, and instead look at every area where an online bank does business, Van Tol said. It could also be rewritten to base assessment on deposits, such as whether a bank’s deposit market share hits a certain threshold.

Ally would be open to such changes, so long it’s not required it to make loans in every location where it has customers, Bergeson said.

“It would be very difficult, if not impossible for us to do that, since we have customers in almost every county in the U.S.,” she said.

Other banks with limited branch networks have similar issues. The $81 billion-asset USAA’s compliance is based on its lending performance in states where it has deposit-taking ATMs. USAA wants the updated law to allow it to be judged on how well it meets the credit needs of the low- to moderate-income segments of its membership, said Charles Mapson, CRA director.

USAA will lobby regulators to add flexibility for “banks that have a large online presence and are call center-heavy, to view their community beyond a geography-based definition of assessment areas,” he said.

Community banks are also hopeful than an updated CRA could provide some relief. Because most community banks have some online presence, an institution might have deposit customers in another part of the country. That could help these smaller banks with their own compliance efforts, said Paul Schieber, an attorney at Stevens & Lee in Valley Forge, Pa., who advises banks on CRA issues.

Community banks now only have a limited geographic area in which to make CRA-eligible loans. If their CRA territories were expanded to include places where it has digital customers, these banks could more easily comply with the law, Schieber said.

If the law was updated in this way, community banks could “lend outside the footprint and maybe it’s an opportunity to get CRA credits for that,” Schieber said.

Bankers and industry groups have stressed that the process is in the extremely early stages and it’s

While regulators deliberate, bankers and industry groups intend to press the case that assessment areas should be expanded.

“We need to take into consideration that everyone has adopted online technology now, and everyone’s business model is changing,” said the ABA’s Shonk.