The upturn in oil prices has brightened the outlook for oil lenders in 2017, but there are plenty of reasons the renewed sense of optimism could be short-lived.

Looking ahead, several factors could once again send prices tumbling.

It remains to be seen, for instance, whether oil-producing countries will follow through on an agreement to cut production and reduce the oil glut. Also unknown is whether the incoming Trump administration will make good on

Moreover, the oil-related bankruptcies are expected to continue at a steady clip in 2017, causing headaches for lenders across the industry.

So even though oil prices have climbed above $50 per barrel in December after plunging to around $30 in February, allowing banks to breathe a sigh of relief, lenders should not completely drop their guard, said Kevin Fitzsimmons, an analyst with Hovde Group.

"Most bankers say you need the price of oil to get over $60 before you see a noticeable pickup in [drilling] activity," Fitzsimmons said.

Lenders around the country, especially in Texas and the Gulf region, rode the boom period to higher profits, financing exploration and production companies that used new technology to drill in Texas, North Dakota and across the mid-Atlantic.

"So much capacity was developed so quickly – and it was fueled by a tsunami of cheap debt," said John Thieroff, an energy analyst with Moody's.

After years of bulking up on energy loans, oil lenders drastically scaled back their exposure to the sector once the crash in prices led to a rise in problem loans.

For instance, at the $72 billion-asset Comerica in Dallas, energy loans as percentage of total loans fell to 5.8% on Sept. 30 from 7.5% nine months earlier. At the $33 billion-asset BOK Financial in Tulsa, Okla., exposure fell to 15.3% from 19.5% over the same period.

The $3.9 billion-asset Green Bancorp in Houston said earlier this year that it would exit oil lending.

Still, some banks, such as Iberiabank in Lafayette, La., said they plan to increase lending to the sector in the coming months.

Here are three X factors that could change the outlook for energy lending in 2017.

Will OPEC follow through on its production cut?

A recent OPEC agreement to slash oil production has sent prices soaring, but some analysts question whether the cartel will fully follow through on its commitment.

OPEC has no official mechanism to enforce a production cut among its 13 members – which include Saudi Arabia, Iran and Venezuela. In fact, following the 17 production cuts that the cartel has agreed to since the early 1980s, members have reduced output by about 60% of their commitments, according to The

"History would tell you that OPEC has a hard time delivering on its commitments," Thieroff said, noting that it typically takes between three and six months to tell whether member countries are complying.

OPEC announced in late November that it would reduce output by 1.2 million barrels per day by January. The announcement sparked a rally in the market, sending prices of West Texas Crude to an 18-month high.

The agreement is designed to curb the supply glut in the market and boost global prices.

Thieroff said he's taking a "wait-and-see" approach to how production cuts play out in the coming months.

There are other reasons, however, for bankers to remain optimistic that global production will slow down.

Earlier this month, a group of oil-producing countries that are not part of OPEC also agreed to cut their output. Eleven countries including Russia agreed to

Will the Trump administration roll back restrictions on drilling?

Oil lenders may be encouraged by President-elect Donald Trump's pro-industry stance on energy. But rolling back certain environmental protections could put unwanted downward pressure on oil prices.

During his campaign for president, Trump promised to "unleash" the country's untapped oil and gas reserves. That could mean removing restrictions on drilling in federal land along the northern coast of Alaska, such as the Arctic Wildlife Refuge.

The perception that the Trump administration will support the energy sector "a bit more incrementally" than President Obama has produced a sense of optimism among oil lenders, Fitzsimmons said.

But there's a downside to keep in mind: More drilling could cause the already low prices to once again tumble. Though prices have recently increased, they remain well under levels seen in the summer of 2014, when prices topped $100 per barrel.

"If regulations change in a way that allow more access to drilling … it likely doesn't help anything," Thieroff said, noting that oversupply was a factor that caused the crash in the first place.

Moody's expects oil prices to stay between $40 and $60 per barrel over the next two years.

Still, Thieroff said that any effort by the incoming administration to upgrade energy-related infrastructure could be a boon to oil lenders.

Pipelines that are currently in place cannot handle the oil capacity. Approvals for projects such as the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline could allow for faster transport.

Will oil-related bankruptcies continue at a steady pace?

It has been a tough year for oil-related bankruptcies, and the trend does not appear to be letting up.

When the energy markets crashed, cash-strapped companies began drawing down lines of credit as a last-ditch effort to pay their bills as many slid toward bankruptcy. Reorganizing under Chapter 11 can be expensive, and having extra cash on hand can give companies a leg up in the process.

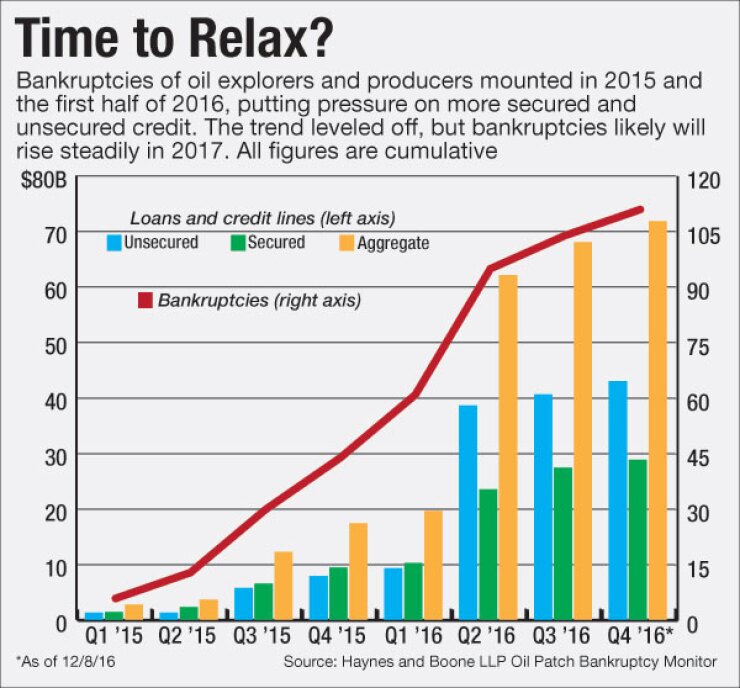

There were 111 bankruptcy filings for exploration and production companies from Jan. 1, 2015, to early this December, representing $71.8 billion in debt, according to the law firm Haynes and Boone.

The pace of filings slowed in the second half of 2016, but they kept coming and won't stop anytime soon, according to industry experts.

"While it's a positive thing for oil to go up, it will have to go up significantly more to pay off all of the debt that's out there," said Robin Russell, a bankruptcy attorney with Andrews Kurth in Houston.

Though banks have taken steps to cut their energy-borrowing bases, they nonetheless remain in the thick of messy bankruptcy negotiations.

"There have been over 100 bankruptcies just this year, so we are not out of the woods," Doug Petno, CEO of commercial banking at JPMorgan Chase, said at an industry conference in November.

Thieroff said he is tracking a "couple dozen" energy companies that are teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

One reason for the continued filings is that their timing often depends on when a company's debt is due and when companies are forced to pay off or refinance their obligations.

Russell said there are a number of takeaways from the recent oil crash.

First is that, in the future, energy companies will likely rely more on unsecured debt to finance their operations now that banks have scaled back on secured lines of credit. Lenders are going to have to grow more comfortable with that financing structure.

The second is that, in a commodity business, the price simply dictates the future of a company above all else. Even the best-run companies can spiral into failure.

"Companies fail even if they have fabulous management teams," Russell said.