-

This American Banker special report digs deep into a topic of critical importance to the banking industry, as well as the country at large. We shed light on the steps banks are taking to make it easier for small business borrowers get loans, what's happening with the competition and why access to credit is so much tougher for African-American entrepreneurs.

February 16 -

Five Star Bank is the latest financial institution to settle claims that it avoided lending to minorities. More redlining cases can be expected, industry experts say.

January 21 -

Some banks try to justify tight underwriting standards by arguing that borrowers with lower credit scores and those who can only afford lower down payments are more likely to default. But the research supporting this argument is based on outdated analysis of high-cost, risky loans.

October 22 -

Carver Bancorp in New York has named a new chief lending officer and president of its community development unit.

November 12 -

Carver Bancorp in New York has named a new chief lending officer and president of its community development unit.

November 12

Wanda Henderson is, in many respects, an African-American success story.

The Washington, D.C., resident opened her second hair salon this past summer on 7th Street in the historic Shaw neighborhood. On a recent Saturday afternoon, the shop was bustling. Most of its 10 work stations were occupied. More customers were sitting on black metal folding chairs, waiting for their favorite stylists.

"We got real busy today," she said. "I'm grateful for that."

But when Henderson recalls the difficulty she encountered getting a loan to open the salon, Wanda's on 7th Street, the tone of her voice switches from satisfaction to something closer to exhaustion.

To open the salon, Henderson needed $100,000. She turned first to banks for the cash. She applied at several institutions — only to be rejected at the "last minute" each time.

"As soon as the applications got to the underwriters, they were denied, for the smallest of reasons," she recalled. Eventually, Henderson was able to piece together the necessary financing, partly from a city grant and the rest from a close friend, but the process took about eight months longer than she anticipated, leaving a bad aftertaste.

"I went through a lot of wear-and-tear going to banks," she said. "I'm not going back."

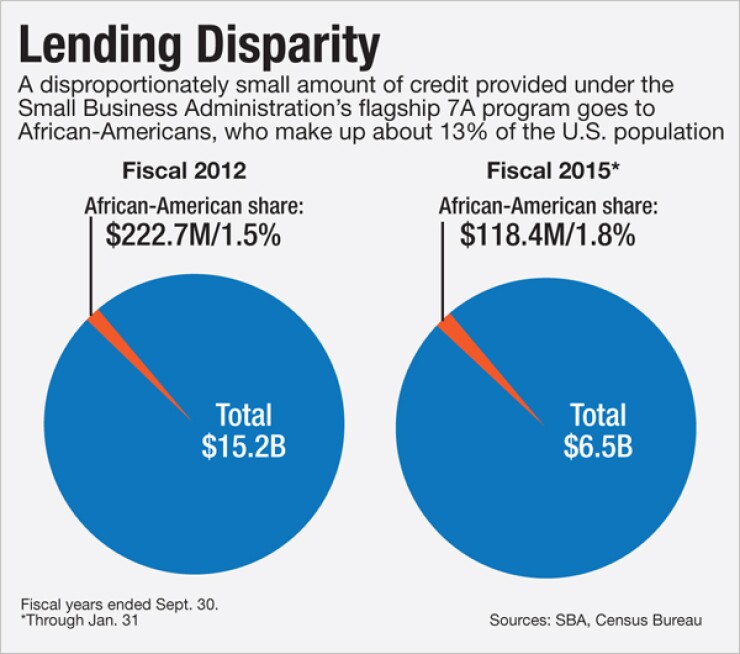

Henderson's experience is typical for black entrepreneurs, a number of statistics suggest. Perhaps no numbers are more telling than those contained in the weekly summaries of loans made as part of the Small Business Administration's flagship 7(a) program. Last year, less than 2% of the $19.2 billion of 7(a) loans SBA guaranteed went to black borrowers.

SBA officials point out that, measured in dollar terms, 7(a) lending to blacks is up more than 40% since 2010, when it bottomed at $238.9 million. Still, the last time black entrepreneurs received more than 2% of the 7(a) pie was 2009 and, even then, the share was a disproportionately small 5%. (For perspective, the African-American share of the population was 13.2% in 2013 according to the Census Bureau.)

A number of factors explain the disparity. The financial crisis hit African-Americans particularly hard, leaving them with far less wealth than white borrowers. Additionally, lingering memories of prejudice, along with cumbersome application processes, have left many African-Americans skeptical of their chances of getting a loan from a bank — with good reason, some observers maintain.

African-American small-business borrowers "don't get the breaks," said William Michael Cunningham, an economist who has studied minority capital access for 20 years.

"The level of exceptions and the tolerance for errors or omissions is much lower than it is for white borrowers. …There're a lot of innovative ideas in the black community, but most never go anywhere mainly due to lack of access to capital. They're stuck in the silo."

The outlook in the venture capital sector is even bleaker. African-American borrowers receive just a fraction of available venture capital funding, according to Cunningham and other experts.

"The gaps become more pronounced when you talk about underserved groups," Javier Saade, associate SBA administrator for the Office of Investment and Innovation, said during a recent panel discussion on investment in minority-owned technology companies sponsored by the Federal Communications Commission.

"A lot of the finance game is like-for-like," with people lending to others in their own ethnic groups, Saade added.

Black entrepreneurs have received a "miniscule amount" of credit over the years, Terrence Thompson, director of public policy in the Americas for Credit Suisse, added during the panel discussion. "This is historical and unfortunate because if you don't have access to capital, you don't even try" to obtain loans and grow businesses, he said.

Credit Suisse launched a program in October to provide financing, business advice and mentoring to black business owners. But the effort, Credit Suisse Entrepreneurs Circle, is aimed at what Thompson described as "proven companies," where credit needs run to the millions of dollars.

Thompson said he hopes other banks will follow Credit Suisse's example and start their own programs to assist African-American entrepreneurs. Even if that occurs, though, there's little chance programs modeled after Entrepreneurs Circle would move the needle much on capital access. According to the SBA, four out of every five loan applications it receives from black and Hispanic entrepreneurs are for $150,000 or less.

Carolyn A. Thomas, owner of the C.A.T.WALK Boutique in Washington, would be satisfied with as little as $5,000. Thomas has never applied for a bank loan, supporting her five-year-old boutique with income from her full-time job. She described the amount of paperwork necessary to secure a loan as intimidating and said she worries her business doesn't generate a large-enough cash flow to qualify.

Thomas likened her situation to a "vicious cycle" that at the end of the day leaves her without the funding she needs to make critical investments: improved marketing, a more robust website, and fabric and other materials to allow her designers to make clothes.

SBA's strategy has been to incentivize lenders to make more small loans. In recent years, the agency has taken several steps to boost the amount of credit available to minority borrowers, eliminating fees and relaxing underwriting standards on smaller loans.

The SBA is "definitely trying to get banks" to make smaller loans, said David Lucht, chief risk officer at the $565 million-asset Live Oak Bank in Wilmington, N.C., the nation's second-biggest 7(a) lender. Live Oak is "in alignment" with the agency's desire to help minority-owned businesses, Lucht said, adding that he is working full-time on an initiative aimed at increasing the number of small loans the bank makes.

So far, though, the SBA's effort has yielded mixed results. Its most-recent lending report, released Jan. 17, showed blacks received loans totaling $118.3 million. While 15% ahead of last year, it still amounts to just 1.8% of the $6.5 billion in 7(a) loans made through the first four months of the agency's 2015 fiscal year, which began Oct. 1.

Carver Federal Savings Bank, the nation's largest African-American and Caribbean managed bank, is going a step further. Michael T. Pugh, the New York lender's president and chief executive, is developing a small-business microloan product that would offer borrowers $2,500 to $10,000 in credit. The $644 million-asset Carver hopes to begin marketing the loans this spring, he said.

Experts attribute the dearth of credit provided to blacks to a number of causes.

Certainly, the economic woes of the past five years hit African-Americans hard. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate for African-Americans was 10.2% in December, significantly higher than the national rate of 5.6%.

Loan officers are often unfamiliar with minority communities, where they have few contacts and scant knowledge of local business conditions, said Gregory Squires, chairman of the sociology department at George Washington University. Lacking those critical connections, lenders seldom take the time to help African-American borrowers iron out problems in their applications.

"Blemishes that might be overlooked for other borrowers are viewed as a reason to reject" black applicants, Squires said. He mentioned what researchers have described as the "thick file" phenomenon where files of white borrowers were noticeably thicker than files for African-American applicants, who had received little extra assistance.

Teri Williams, president of OneUnited Bank in Boston, agreed that lenders need to be more sensitive in their dealings with African-American borrowers, but she noted that financial education is also an issue. Oftentimes, Williams said, African-American entrepreneurs, even some with very successful businesses, "may not have their [loan] packages together or have their financials at their fingertips.

"But that doesn't mean they don't have value," she added.

In a similar vein, a number of the small-business loan applications Carver has received from African-American borrowers sometimes lacked critical components such as detailed financial statements and business plans, Pugh said.

In such instances, Carver usually does not reject the borrower. Instead, it refers them to nonprofit groups or provides additional in-house technical assistance to get the applications into shape.

"That's the real value of a community bank and it's part of the Carver value proposition,"

Problem is, black entrepreneurs rarely receive that level of assistance and, as a result, tend to avoid banks, said Janet Jones, a Detroit bookseller.

"We saved up and did what we needed to do for ourselves," said Jones, a retired teacher who started selling books in 1989. "That's the reality. Banks were never favorable for business loans to African-Americans. I can remember a time when we didn't have any African-American bank tellers in Detroit" beyond minority-owned banks.

Jones admits she is an exception to her rule. She obtained a line of credit when she moved her shop, Source Books, into its current home on Cass Avenue in midtown. Still, Jones said she probably would not have sought financing without advice and assistance from nonprofit agency Midtown Detroit Inc.

Jones said she sought financing on her own in the early 1990s, only to be quickly shot down by a bank. "I thought maybe I could at least get some advice or information, but I received a very cold response," she recalled. "I left there not feeling very good."

The financial services industry's ongoing failure to fully address the capital needs of black entrepreneurs is pushing more to explore alternative lending sources, particularly crowdfunding, Cunningham said. Indeed, these days Cunningham said he spends much of his time helping black-owned small businesses develop crowd-funding pitches.

Cunningham helped Thomas design a crowdfunding campaign that netted nearly $2,000. While that isn't as much as Thomas had hoped to receive, she said the cash "will go a long way" toward buying supplies for her designers.

Cunningham said he is optimistic crowdfunding will become an important source of capital for black entrepreneurs, although he admitted the results so far have been uneven at best.

"It's showing promise but not showing results," Cunningham said. "It's a wealth issue. Every dollar in the black community is stretched to the max."