Whose American dream?

Decades after redlining and housing discrimination were outlawed, nonwhite Americans still own their homes at far lower rates than white Americans. What’s the Biden administration going to do about it?

Vanessa Gail Perry bought her home in Silver Spring, Md., when she was 33. At the time she was working as a senior economist at Freddie Mac, earning a handsome wage and financially independent. But even so, she needed help to close the deal.

“I was lucky,” said Perry, now an associate dean for faculty and professor of marketing at the George Washington University School of Business. “My parents gave me the 20% down payment, and my closing costs and fees were paid by my employer. If I hadn’t had that gift, it’s unlikely I would have been able to afford to buy. I would have been unable to qualify for a conventional loan and both the interest rate and payments would have been substantially higher and prohibitive.”

The American Dream is an idea that is as old as America itself, but the promise of upward mobility unencumbered by constraints of class or status has never been entirely sincere. Freedom to settle the American frontier necessarily meant the forcible relocation of Native peoples; the freedom to acquire wealth for hundreds of years included the freedom to own other people.

The American Dream has evolved just as America has evolved, but today, homeownership has emerged as the primary public policy tool for helping Americans achieve wealth and self-reliance. Nearly two-thirds of the nation’s 140 million housing units are owner-occupied, conferring an average net housing wealth to those owners of over $150,000.

This is a statistical way of saying that buying a home is the main way Americans obtain real, tangible wealth. And increasing homeownership — particularly among low-and moderate-income Americans — has been a policy goal of the federal government for decades, said John Weicher, a senior fellow and director of the Hudson Institute’s Center for Housing and Financial Markets.

“For the vast majority of the middle class, the equity in their home is their most important asset,” said Weicher, a former economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, who served as federal housing commissioner at the Department of Housing and Urban Development from 2001 to 2005. “If you bought a house 40 years ago, you’ve enjoyed a significant increase in wealth that can be passed on to the next generation.”

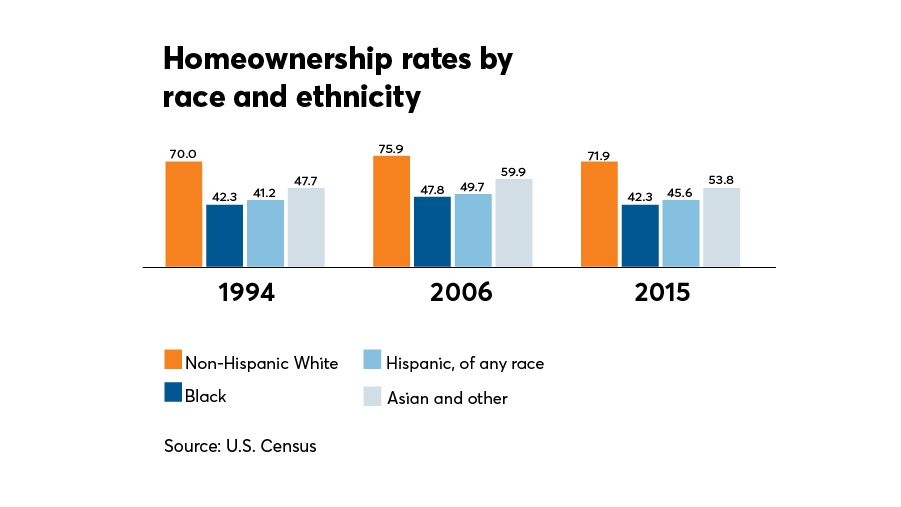

But white Americans today enjoy the equity-building benefits of homeownership at significantly greater rates than nonwhites. In the third quarter of 2020, 46% of Black households owned their own home, compared with 51% of Hispanic households, 61% for Asians and 76% for whites, according to data from the Census Bureau. And that racial gap in homeownership is actually greater today than it was in 1968, when the Fair Housing Act outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion and national origin.

The current discrepancy in homeownership rates is actually of a more recent vintage, however. Homeownership rates increased for all racial and ethnic groups between 1994 and 2006 — particularly for middle-income families. But the housing crash erased all of the gains among Black families between 2006 and 2015 and roughly half of the gains for Hispanics and Asians, according to a 2017 study by the St. Louis Fed.

College-educated Black and Hispanic families fared far worse than other groups, the study found. Between 2007 and 2013, the average home value among college-educated Black families fell by 51%, while home values for Hispanic families dropped 45%. By contrast, the average home value fell 25% for white families and 6% for Asian families, the report found.

“What makes for wealth accumulation is the ability of a family to sustain and pass along wealth — it’s homeownership,” said Karen Petrou, co-founder and managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics, and author of a book to be published in March, “Engine of Inequality: The Fed and the Future of Wealth in America.” “Economic inequality is a cumulative process, and if families lose even a few years of homeownership, those are years they cannot get back.”

“It’s like pushing a boulder up a hill. The forces that have created this inequality are so entrenched and huge that moving them is a monumental task.”

And because Black, Indigenous and people of color were more impacted by the financial crisis — and because many continue to live in de facto segregated neighborhoods that have had less home price appreciation — they have less wealth to pass down to the next generation. Some experts say that puts some of these households at a further disadvantage when forming their own households and seeking to buy a home.

“It’s like pushing a boulder up a hill,” said Michael Banner, president and CEO of Los Angeles LDC, a community development financial institution that invests in distressed neighborhoods.

“It’s mind-boggling,” said Banner. “The forces that have created this inequality are so entrenched and huge that moving them is a monumental task.”

Now, in 2021, the Biden administration has made an explicit goal of pushing that boulder up that hill. But what can the Biden administration do to reverse a multigenerational legacy of discrimination and deferred American Dreams?

Vanessa Gail Perry, associate dean for faculty and professor of marketing at the George Washington University School of Business, stands outside her home in Silver Spring, Md. Perry has dedicated her career to "exposing these real issues and the problems of real people with respect to wealth-building."

Vanessa Gail Perry, associate dean for faculty and professor of marketing at the George Washington University School of Business, stands outside her home in Silver Spring, Md. Perry has dedicated her career to "exposing these real issues and the problems of real people with respect to wealth-building."

The roots of ‘risky’ lending

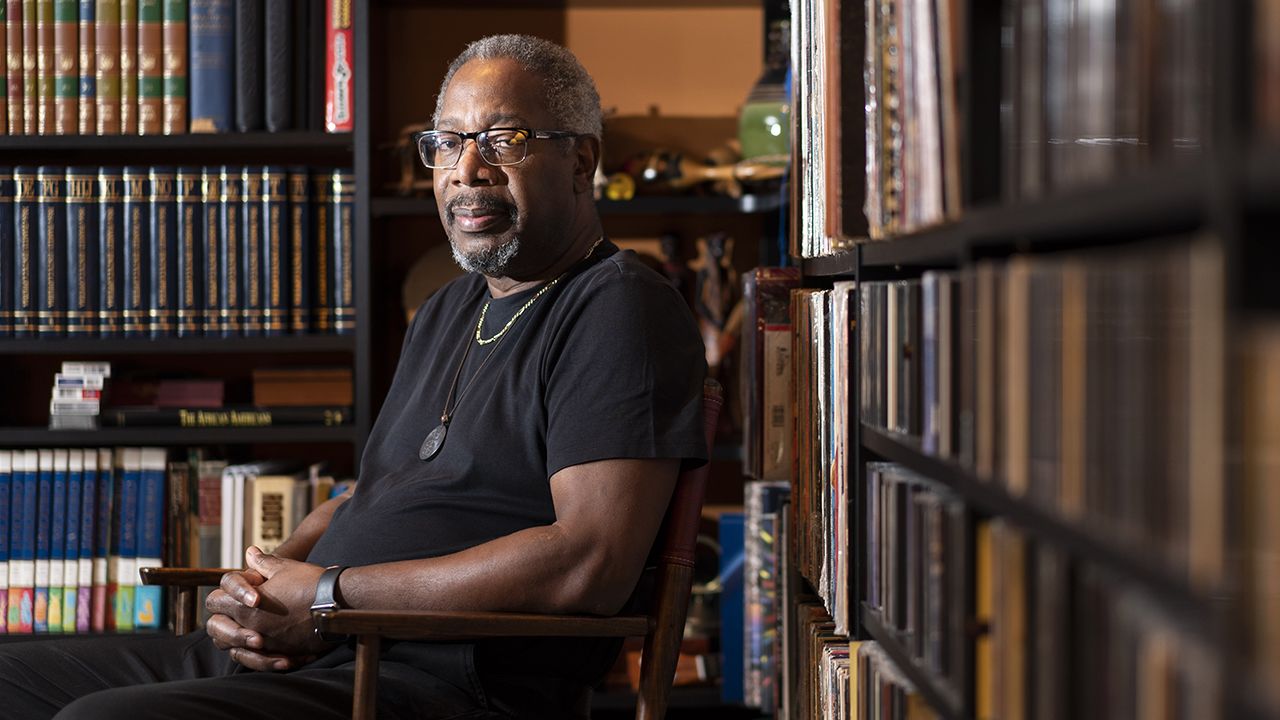

Maurice Jourdain-Earl has lived the legacy of housing discrimination in the United States.

Jourdain-Earl, co-founder and managing director of ComplianceTech, a home mortgage data analysis firm, grew up in segregated housing on the South Side of Chicago, where his mother settled after leaving Mississippi during the Great Migration. His grandfather was a sharecropper.

The roots of modern-day lending discrimination can be traced to federal policies that began toward the end of the Great Depression, and flourished in the 1950s. A federal agency, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, created maps beginning in the 1930s that used a color code scheme to determine whether banks could make home loans there. Neighborhoods with immigrant, Black or Latino populations were colored red, and thus redlining was born.

“Growing up abjectly poor, I had a goal of being a millionaire,” said Jourdain-Earl, who was the first in his family to go to college, graduating from DePaul University when he was 20. To reach that goal, he said, “I focused on working in environments where money was being made.”

“There’s a problem of inequality in the lending industry with underwriting disparities, pricing disparities and redlining. Some of the issues are repercussions from slavery and 150 years of Jim Crow that still exist today.”

His first professional job was checking buy and sell orders with a municipal bond brokerage; he worked his way up in the banking and finance industry to brokering bonds on his own and packaging mortgage-backed securities. In 1992 he founded ComplianceTech, the first tech company of its kind to analyze lending data collected by mortgage lenders under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975.

That law was designed to identify lending patterns that lead to redlining and other forms of discrimination, and Jourdain-Earl said that minorities are more often steered into loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service.

Those loans are insured and are designed to be available to lower-income borrowers, featuring lower down-payment and credit score requirements and higher debt-to-income ratios. But these so-called nonconventional loans are also more expensive, and tend to have higher interest rates and insurance premiums.

The difference between a “conventional” and non-conventional loan is that conventional loans adhere to standard underwriting guidelines set by mortgage finance giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, collectively known as the government-sponsored enterprises. The schism between the costs and conditions of conventional versus nonconventional loans is a driving force that keeps homeownership out of reach for many minority borrowers, Jourdain-Earl says.

Though FHA loans typically have lower interest rates, they can be more expensive over the life of a loan because borrowers typically must pay both annual and monthly mortgage insurance premiums. The current upfront premium is 1.75% of the loan amount, which is added to the cost of the loan.

“The system we have now is a dual mortgage market — one white, one Black. Separate and unequal,” Jordain-Earl said. “It throws all people of color in a box that says they are poor, which is just not true today.”

Jourdain-Earl has found that 80.8% of GSE loans were made to white borrowers, compared with 3.6% to Black and 7.7% to Hispanics. For FHA, VA and Rural Housing loans, 71.8% went to white borrowers, 11.5% to Black borrowers and 13.3% to Hispanics, the data shows.

“Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac predominantly serve the finance needs of whites and Asians,” Jourdain-Earl said. “Many minority subprime and FHA borrowers could qualify for lower-cost conventional loans purchased by Fannie and Freddie. But that hasn’t happened, even when the GSEs offer loan programs with flexible terms designed to compete with FHA.”

Homeownership preservation is another major problem. During economic downturns such as the 2008 recession, and more recently the COVID pandemic, the government has leaned on the GSEs to help Americans stay in their homes. The result is more white homeowners getting relief.

“There’s a problem of inequality in the lending industry with underwriting disparities, pricing disparities and redlining,” Jourdain-Earl said. “Some of the issues are repercussions from slavery and 150 years of Jim Crow that still exist today.”

The absence of a down payment is one of the biggest impediments to homeownership for low-and moderate-income Americans, particularly for Black and Hispanic homebuyers, said Perry. The median down payment among Black and Hispanic homebuyers is 3.5%, compared with 10% for all homebuyers in 2018.

A big driver for those racial disparities in down payment — and, by extension, the driver for how these disparities in successful homeownership remain so firmly entrenched — is the presence or absence of intergenerational wealth.

Maurice Jordain-Earl, founder of housing data firm ComplianceTech, says the racial disparities in homeownership are a direct result of explicitly exclusionary laws that date back generations. While those policies are no longer on the books, they still have a powerful effect on intergenerational wealth.

Maurice Jordain-Earl, founder of housing data firm ComplianceTech, says the racial disparities in homeownership are a direct result of explicitly exclusionary laws that date back generations. While those policies are no longer on the books, they still have a powerful effect on intergenerational wealth.

Intergenerational wealth

Perry recalled working at Freddie Mac in 1994 and chatting with a top economist about how much trouble minorities had in obtaining mortgage credit. Her colleague said he couldn’t understand why anyone would ever take out a car loan, and went on to explain that he had purchased his first car with money in a trust fund established by his grandparents.

“He honestly was trying to figure out why people would be so stupid to take out a car loan. And I said, ‘What about people who don’t have trust funds?’” said Perry. “And he shrugged it off and said, ‘Well, they should save.’

“At that moment I realized that the people responsible for policy analysis had absolutely no clue — there was a complete lack of understanding,” she said. “From that moment on, I dedicated myself to exposing these real issues and the problems of real people with respect to wealth-building.”

Wealth confers benefits — this is as true today as it has ever been. And wealth obtained through homeownership tends to confer benefits not only in one’s own lifetime, but for generations to come. A recent study by the Urban Institute found that having a parent who owns a home increases the likelihood that a young adult between the ages of 18 and 34 will also become a homeowner.

The study also found that parents who remained homeowners from 1999 to 2015 — through the crucial years of the 2008 housing crisis — tended to accrue enough home equity to pass on to the next generation. During that period, 71.5% of white parents remained homeowners, while only 31.4% of Black parents did, the study found. What is more, the study found that young adults were more likely to become homeowners if their parents’ wealth was $200,000 or more. While more than 50% of white parents met that threshold, only 10% of Black parents did.

“Parents or families with more wealth can help with a down payment — so the impact is intergenerational,” said Karan Kaul, senior research associate at the Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center. “If your parents aren’t homeowners, then right away, you are less likely to be a homeowner.”

The long-term impacts of COVID-19 on homeownership are unknown, but Kaul notes that, combined with the last financial crisis and Great Recession, there is the potential “for three generations to be impacted by housing losses.”

“Economic inequality is a cumulative process, and if families lose even a few years of homeownership, those are years they cannot get back.”

But homeownership cannot be observed in a vacuum. Gregory Squires, a sociology professor at George Washington University, said there are many other racial disparities — in education, employment, income and health care, to name a few — that have significant implications for the minority homeowner experience, and that can profitably account for why those homeowners pass on less wealth to their heirs than white homeowners do.

“Everybody is talking about structural racism today, about homeownership, wealth and the racial gap,” Squires said. “It is the case that a high share of wealth for minorities comes from homeownership. But they also tend to purchase homes that have less value, are in minority neighborhoods where property values are depressed and buy later in life, so they have fewer years of wealth accumulation for home equity.”

“The notion that housing is the solution to inequality and wealth disparities is a problem,” he said. “There are all these other areas — education, criminal justice, labor markets — that affect different groups of people differently. Housing alone isn’t going to eliminate all those other problems. We have probably focused too much on homeownership as the solution to structural inequality.”

Fixing the post-2008 fixes

The experience of Perry, Jordain-Earl and others who have studied homeownership trends also illustrates the complicated relationship between lending institutions, minorities and the federal government.

If you’re reading American Banker, there’s a good chance you know there’s a difference between an FHA loan, a VA loan and a GSE conventional loan. But most homebuyers don’t understand those distinctions and the differences that they represent in cost. And the policies that end up steering minority borrowers away from conventional loans and toward costlier loans were largely a byproduct of the housing bubble and policies put in place by the Obama administration in its wake.

“FHA is in a position to take a little more risk than private lenders, as part of the government. They are supposed to do that, but not to lose money in the process,” said Weicher.

Banks have also largely vacated the FHA loan market since the 2008 financial crisis, going from roughly 50% of FHA originations pre-crisis to less than 10% post-crisis.

That exodus began after President Obama took office, when the Justice Department initiated False Claims Act investigations against banks for allegedly certifying FHA loans that were eligible for federal mortgage insurance. Lenders were required to conduct quality control reviews of loans that defaulted within the first six months to ensure they complied with the FHA’s guidelines.

The Justice Department’s approach made both legal and political sense; the department said in a November 2014 statement that the False Claims Act investigations were meant to fulfill “the administration’s priorities to hold the financial industry accountable for its part in the gross misconduct that led to the housing and mortgage crisis.”

By 2014, more than $4.6 billion had been collected in False Claims Act settlements from a number of banks, including Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, SunTrust and U.S. Bank. Many banks learned the lesson that FHA loans — which already brought in marginal profits — weren’t worth the trouble.

“The real question for me is should we be in the FHA business at all,” Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, said in 2014.

The Obama administration also oversaw a wholesale revision of how regulators evaluate banks’ capital adequacy, and the Fed’s stress testing regime in particular has had dramatic implications for what kinds of loans banks will hold on their books. Residential mortgages — previously thought to be risk-free — faced dramatic loan losses in the stress tests, especially for riskier loans. The result is fewer institutions willing to offer riskier mortgage lending products.

“If we tell banks that we want them to do well in a crisis and that we are protecting the public against another bank failure by performing stress tests , that’s a reason why banks don’t make loans to certain borrowers,” said Jeff Naimon, a partner at the Buckley law firm.

The stress tests increased capital requirements for mortgages because those assets drove the 2008 financial crisis, and loosening them might stoke fears that regulators are inviting a similar result. But that crisis, Petrou said, was driven more by well-heeled borrowers leveraging their equity than subprime borrowers obtaining mortgage credit.

“The whole assumption of the current risk-based capital system is that subprime borrowers are more risky, but none of the evidence supports that,” she said. “There is a growing body of research showing that it was prime borrowers who really drove losses during the financial crisis by leveraging their houses as ATMs.”

If lowering capital retention requirements were targeted to lower-value homes, it would provide meaningful benefit to families seeking to enter the housing market for the first time without setting the stage for another housing bubble, Petrou said. The incoming administration will have to find a way to balance the interests of expanding mortgage access against systemic risk, she said, but focusing on lower-value homes is a profitable place to start.

“There needs to be some policy initiatives — including incentives for low-balance loans for banks to originate home loans of $150,000 or less.”

“There needs to be some policy initiatives — including incentives for low-balance loans for banks to originate home loans of $150,000 or less," she said.

The ultra-accommodative interest rate policies put forward by the Fed since 2008 — and especially since the onset of COVID — has also had a secondary effect of making it harder for lower-income earners to make low-risk interest gains on their savings, she said. That means it is taking longer for many BIPOC savers to generate sufficient savings for a down payment, she said.

"You can never regain equitable ground as long as interest rates are as low as they are and no one can save for a down payment," she said.

If the Biden administration wants to make the American Dream as real for nonwhite Americans as it has been for white Americans, it has its work cut out for it. But a significant part of closing that disparity of experience means finding sustainable ways to make homeownership more available and more profitable for nonwhite borrowers — and banks.

“FHA doesn’t have to be the main option for Black and Hispanic borrowers,” said Perry. “If we know that credit scores and debt-to-income ratios are nothing but measures of wealth disparities that reflect discrimination, then there are ways to enhance access to credit and homeownership opportunities for people of color.”