Numerous investors in Cecil Bancorp — including the Treasury Department — will take a hit from the struggling Maryland company's bankruptcy plan.

The Elkton, Md., company plans to sell its $211 million-asset bank to an unnamed investment group as part of a $30 million recapitalization. Management has taken Cecil, which has been operating under a prompt corrective action since 2015, into bankruptcy after it failed to resolve a financial impasse with holders of its trust-preferred securities.

The plan would wipe out entities that hold Cecil’s common stock, including 1st Mariner Bank, which went through a similar reorganization in 2014. 1st Mariner owns somewhere between 10% and 24.9% of Cecil’s common stock, according to court and regulatory filings.

The Treasury will also get stung. Cecil, the third-largest remaining participant in the Troubled Asset Relief Program, plans to repay just $880,000 of the nearly $12 million it received from the government in 2008. The company also owes the Treasury nearly $6 million in unpaid dividends.

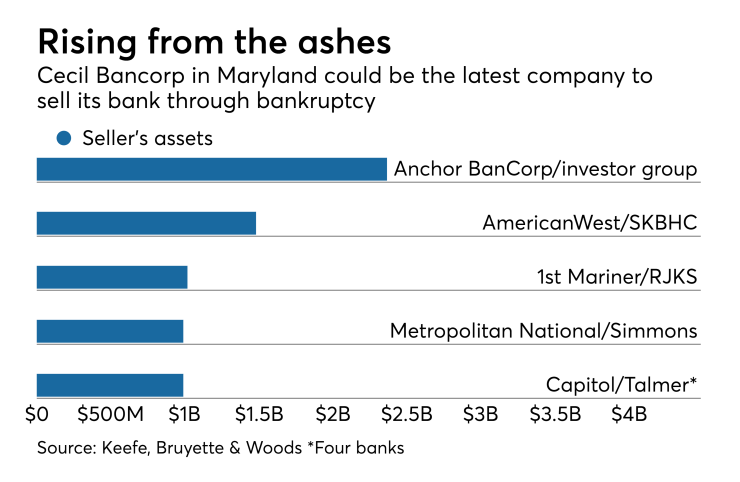

The aggressive move — resembling one that

“We’ve been … in a defensive crouch ever since I’ve arrived, protecting our capital account, cleaning up the bank’s balance sheet, trying to improve its income statement,” Spiro said.

Cecil filed a prepackaged bankruptcy application on June 30 that outlined proposed settlements with debtors, including a minimum distribution of $1 million to address claims from trust-preferred securities holders. While Cecil refused to identify its investors, the filing notes that certain directors and officers are among those participating in the recapitalization.

Efforts to reach the Treasury, 1st Mariner and the entities that own Cecil's trust-preferred securities were unsuccessful.

As part of the bankruptcy process, other bidders have an opportunity to present a better offer.

The bankruptcy filings disclosed that Hovde Group spent three years trying to sell the bank, or find an investor, without going through bankruptcy. More than 75 banks and individuals passed. The filings note that Cecil has binding subscription agreements for $24 million in capital, or 80% of what it aims to raise.

Cecil’s board and management team would remain in place, though the investment group would be allowed to add directors, the filings reveal.

“After many weeks of trying to negotiate something other than a bankruptcy, we finally agreed,” Spiro said. The trust-preferred creditor “essentially said they would prefer that Cecil go through a bankruptcy process, because they wanted something that is totally transparent.”

Spiro, a veteran banker who has run two community banks in northern Virginia and was a regional president for First Horizon from 2002 to 2007, has labored for four years addressing Cecil’s issues. Her team has resolved more than $70 million of high-risk and nonperforming assets.

The remaining loans are “very typical of a community bank portfolio,” Spiro said. Cecil plans to focus on consumer loans, including mortgages, along with small-business lending and owner-occupied real estate, she said.

“We’ll do some CRE loans, but those will be very carefully underwritten,” Spiro said. “They’ll be properly sized for our capital account and our risk appetite.”

Northeastern Maryland, where Cecil operations, is bouncing back from the recession. Elkton is less than 25 miles away from Wilmington, Del.

Several major corporations, including Amazon, the manufacturer Truaire and the German grocery chain Lidl, are expanding in the area.

“Those three [companies] alone are creating 1,000 new jobs,” said Christopher Moyer, director of the Cecil County Office of Economic Development. “Our job base is set to increase by 8% in the next 18 months.”

Another major company is expected to soon announce a project that should add another 450 jobs, Moyer said.

Cecil’s status as a locally based community bank could give it an advantage as it aims to recover its footing, Moyer said. “They have a name that resonates in the community because they’re part of the community,” he said.

In its current state, Cecil’s ability to add customers has been limited. An infusion of $30 million in capital could allow it to compete for new clients.

“This can be a highly functioning, highly profitable community bank once it is recapitalized,” Spiro said.

“There’s tremendous, pent-up demand for community bank lending, community bank credit and deposit activities of all kinds,” Spiro added. “You have to remember, we’re the last community bank standing in the northeast corner of Maryland. All the others have been consolidated out of the market or have failed.”