Something has been missed in all the fuss about

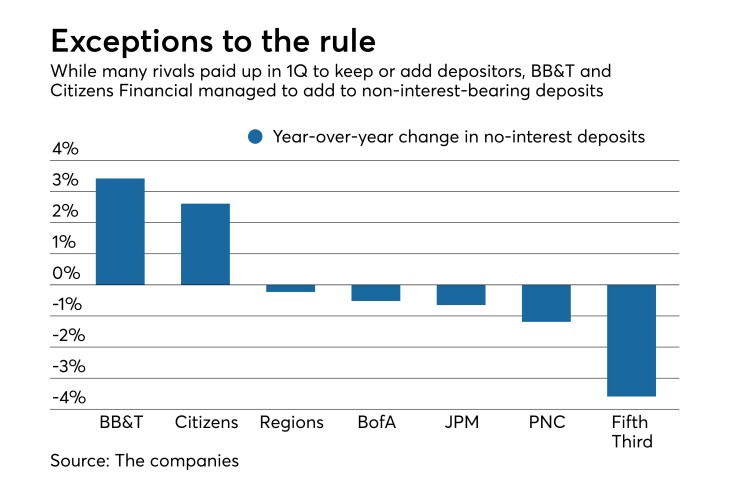

BB&T and Citizens Financial Group added non-interest-bearing deposits in the first quarter, going against the grain of industrywide results. Most large banks reported a gradual and predictable decline as customers began transferring cash into savings and other higher-yielding accounts. Regions Financial, meanwhile, reported a smaller decline than many competitors.

Non-interest-bearing deposits are important for a number of reasons, not least of which because, as a source of no-cost funds, they provide a much-needed boost to margins. They also typically are held in a customer’s primary bank account — the one that consumers regularly use to deposit checks or pay bills.

The opportunistic increases highlight the investments some banks have made in data analytics and elsewhere to protect their stockpiles of cheap deposits. More important, they underscore the fact that the war for deposits is multifaceted and that there are niche battles more regionals could win.

“This will definitely be something that differentiates banks,” said Brian Klock, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Non-interest-bearing deposits at BB&T rose more than 3% year over year, to $55 billion at March 31, and by just above 2% at Citizens, to $28 billion. At other regionals and at larger banks, such as JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, for instance, such deposits declined by around 1%.

Both BB&T and Citizens have focused intensely in recent years on attracting new business from small and midsize companies — and, in the process, new sources of deposits, according to Klock.

“Those deposits tend to be stickier, and they’re going to be cheaper,” Klock said.

Asked about the uptick in non-interest-bearing deposits, executives at Citizens said during their quarterly earnings call in late April that expanding the portfolio has been a priority. One way they have done so is by investing in new technology to more efficiently target new customers — or existing customers who could add deposits to their accounts — through direct mail instead of mass promotions.

“I think the big thing for us has been the improvement in analytics and targeted offerings,” Brad Conner, head of consumer banking at the $150 billion-asset company, said during the call.

Conner also pointed to the launch of the company’s line of so-called “platinum” suite of products. Affluent customers, for instance, can waive a monthly account maintenance fee of $25 if they carry a balance of $25,000 in their combined deposit and investment accounts.

Regional banks, more broadly, are “rethinking the mix” between how much they spend on analytics versus more traditional deposit-gathering channels, such as opening branches, according to Leo Rinaldi, director of marketing and distribution at Novantas.

In fact, regionals have spent the past five years — a period marked by ultralow rates — scooping up the cheapest deposits in droves.

BB&T and Regions, in particular, have significantly increased the percentage of non-interest-bearing deposits in their portfolios, according to a recent report from Moody’s, which described such deposits as the “crown jewel of U.S. banks’ franchise value.”

At BB&T, non-interest-bearing deposits made up 33% of total deposits in 2017, compared with just 23% five years earlier. At Regions, meanwhile, they made up 37%, compared to 31% in 2012.

Among the top 14 U.S. banks, the median was 29%.

“When rates were extraordinarily low for a number of years, that, in retrospect, was a great time to go out and gather as many non-interest-bearing deposits as you could, because they become more valuable when rates inevitably begin to rise, said Allen Tischler, an analyst at Moody’s.

But the looming question for banks is: How long can they keep it up?

With the Federal Reserve expected to announce

An “outright contraction” of non-interest-bearing deposits across the industry during 2018 is possible, according to Tischler.

As that happens, the rates banks pay to depositors on other low-cost products, such as interest-bearing checking and savings accounts, will become more important.

On that point, big banks may ultimately have an advantage. While

Overall, big banks’ cost of deposits is “superior, meaning lower,” than their regional competitors, according to Tischler.

“They seem to have been adept at gathering and holding on to low-cost deposits more generally,” he said.