-

WASHINGTON The Federal Reserve Board issued a proposal Monday that would require certain financial institutions that have been assigned Legal Entity Identifiers to include that information in their regular reports, a first but tentative step toward broader reliance on the universal counterparty ID.

March 16 -

Regulators unveiled plans Monday to broaden the use of "Legal Entity Identifiers" and launch a pilot program designed to get more information on bilateral repurchase agreements.

October 6 -

More robust risk management frameworks and technology infrastructures are at least as important as higher capital standards in preventing another global financial crisis.

December 11 -

A dry-as-dirt technical dispute over unique codes used to identify market participants has roiled a global effort to standardize financial data.

October 12 -

Lacking the authority to control fellow regulators' data operations, the Office of Financial Research may still play an important risk management role — but only by getting along with other agencies.

September 10

WASHINGTON Of all the lessons learned in the financial crisis, perhaps the most fundamental was that neither financial companies nor their regulators knew how exposed the system was to toxic assets, and there was no way to find out.

In part to address that failure, the Dodd-Frank Act created the Office of Financial Research and gave it power to set standards and collect data from market participants to get a better handle on interconnections between firms. The data agency has helped to push the Legal Entity Identifier, now the benchmark standard for financial standards, in an attempt to identify and differentiate between companies and their sometimes confusing web of affiliates.

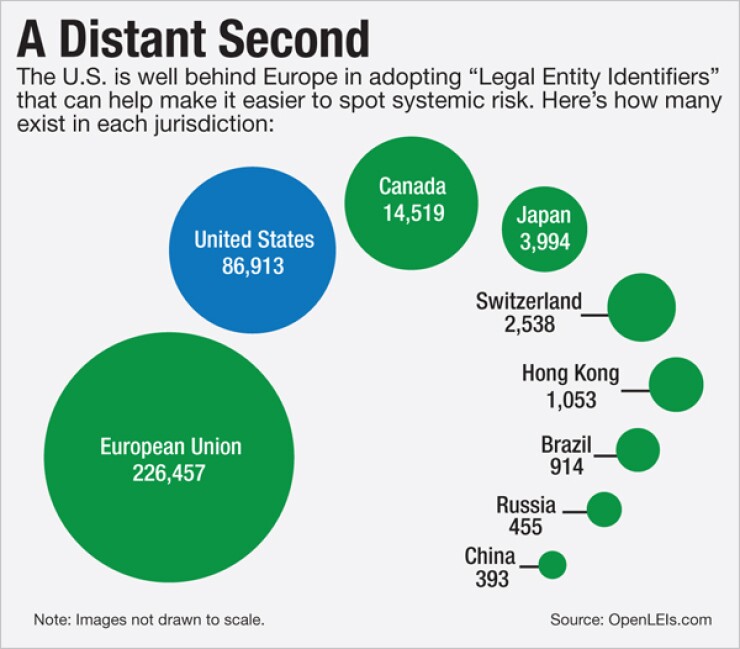

While the LEI was widely viewed as a positive by the industry and regulators, its adoption in the U.S. has been slow and behind the pace set by European countries. To date it is still not even universally recognized by U.S. or foreign regulators. One reason is that despite its importance and its potential for spotting danger areas ahead of a new crisis, the issue has never been a top priority for banks or policymakers.

"I liken it to working on the plumbing -- this is an infrastructure issue," said Matthew Reed, the chief counsel of the OFR and the chairman of the LEI Regulatory Oversight Committee. "This is not always at the front of the agenda when you've got a mandate you're trying to satisfy. Getting this higher up in the agenda has been a challenge."

One reason for that is it has proven expensive and time consuming for firms to embrace the LEI.

"I suspect it's because the overall profound operational burden that is on every one, the banks and the regulators," said Karen Shaw Petrou, managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics. "It's a lower-priority operational agreement for everybody, and it's taking up a lot of time."

Still, the need to easily identify financial entities is clear knowing with whom one is doing business is the cornerstone of finance and commerce. For centuries those relationships were personal and institutional, but as markets have become more global and more interconnected, the lines between one business and another have blurred. Mergers and acquisitions, as well as the prevalence of interstate and international transactions make the need for a numeric identification apparent.

A number of systems have arisen to meet those demands over the course of the 20th Century. The American Bankers Association, for example, established a bank routing number system to facilitate interbank transfers in 1911. Individual firms also developed their own internal systems to keep track of departments and affiliates systems that often remain in place even after mergers and acquisitions. Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters also attempted to create cross-corporate tracking systems, but they were largely proprietary.

U.S. regulators also developed their own tracking systems over time, including the Federal Reserve's Research Statistics Supervision and Discount Identification number, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp's certificate number and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency's charter number. None of those tracking numbers are the same, however, and are limited to the portion of a business that is covered by the individual regulator.

The financial crisis illustrated precisely why that polyglot tracking system was too inefficient to be useful when assessing systemic risk. When mortgage-backed securities nosedived, firms struggled to quantify the extent of their exposures. Companies that traded in unregulated over-the-counter derivatives, or swaps, also struggled not only to understand their exposure but even to know who the counterparties to their contracts were.

As part of its Dodd-Frank mandate, the OFR in November 2010 issued a policy directive that laid out a framework and governance structure for a global LEI system, which was later adopted by the G20 and other global regulatory bodies like the Financial Stability Board. Under the system, the Global LEI Foundation whose board members are drawn from financial firms and non-governmental organizations all over the world endorses Local Operating Units, which assign LEIs regionally. The Depository Trust & Clearing Corp., for example, is the regional operating unit for the U.S., while the London Stock Exchange assigns LEIs in Britain and the Dutch Chamber of Commerce assigns LEIs in Holland. LOUs to date have assigned just over 363,000 LEIs worldwide.

Reed said the structure of the LEI system has been an important element in its growth as the universal identifier, because all stakeholders have enough buy-in to push for its success.

"We wanted the private sector to develop, own and manage this, but we wanted the public sector to have an oversight role, so that it would always be freely available information," Reed said. "You don't want to go right back down the hole that you tried to get out of in the first place."

Some jurisdictions, however, are further along in mandating the use of LEIs than others. The European Union, for example, has been the most aggressive in pushing LEI adoption, in part because it resolves the language and record-keeping differences between member country regulators.

In the U.S., the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and Securities and Exchange Commission have required companies entering into swap transaction to include LEI information in their data reporting. The Fed has also issued a proposal that calls for firms that already have LEIs to include them in some reports. But the central bank said that it has no immediate plans to mandate LEI adopting further.

David Strongin, executive director of the Global Financial Markets Association, said that the group and its members have been pushing hard for a universal financial entity identification system precisely because of the data shortcomings that the crisis illustrated. But implementing a global LEI regime takes time and effort, and regulators need to catch up as well as the market.

"I think it's more complicated than just saying, 'There shall be LEIs,' and there they are," Strongin said. "Regulators, just like the firms, have to go through their own internal processes in getting this rolled out."

At least some critics think regulators are taking too long. Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Fla., is planning to introduce a bill this month that would require Financial Stability Oversight Council member agencies including OCC, FDIC and the Fed to move to a LEI tracking system within two years.

Issa said in a March statement that the bill "modernizes the process of financial regulatory reporting, while also increasing transparency throughout federal regulatory agencies."

The administration appears to agree. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew also said in October that more universal adoption of the LEI is "nothing short than having visibility into the risks we face in the future." To that end, the Treasury issued a proposal in January outlining the requirements for Qualified Financial Contracts Recordkeeping that includes an LEI requirement, meaning that companies would need an LEI in order to qualify for government contracts.

The implementation of the LEI system does not end with assigning numbers to banks the "business card" level of data collection that has been undertaken to date. Reed said that once that objective is in place, regulators will begin work on connecting the LEIs to one another. To start, the Global LEI Foundation will connect firms with their wholly-owned subsidiaries the so-called "level two" of hierarchical mapping.

The foundation and LEI Regulatory Oversight Committee could decide to map even further in the future, Reed said, though it has not considered it to date. But he acknowledged that there is potential to expand the LEI system into nonfinancial aspects of global commerce. Many industrial firms that use swaps to hedge their commodity input prices already use LEIs, he said, and it could have wide applications in areas like anti-money-laundering, sanctions compliance and know-your-customer compliance, for starters.

"This is a code designed for financial market participants. Conceivably, if you open a bank account, you're in a financial transaction," Reed said. "Ultimately, I think in the same way we're trying to solve a problem for the financial world, it could be helpful for the nonfinancial world."

Strongin agreed that the potential applications for the LEI are myriad, but said that how narrowly or how broadly the system is applied is largely a function of how broadly it is mandated by financial regulators. But the broad applicability of the system and its obvious utility for international commerce suggests that its use will only continue to grow over time.

"Theoretically, you could use the LEI for any legal entity around the globe. How it takes hold, and who is going to be covered, will be a function of [regulatory] mandate," Strongin said. "If we have this conversation 15 years from now the system will be covered with LEIs small, large, U.S., non-U.S. I think, for most people, it will be the base for systemic risk analysis."