A disappointing second quarter and another CEO departure have created uncertainty about Berkshire Hills Bancorp’s future.

The Boston company disclosed late Monday that Richard Marotta had resigned, just 21 months after taking the helm, and that it will search for a new leader. While Berkshire said Marotta left to pursue other opportunities, his exit comes during a challenging time for the $13 billion-asset company.

Berkshire reported a staggering $549 million loss in the second quarter after taking a large goodwill impairment charge that reflected the deteriorated market value of past acquisitions. It also set aside more funds to cover potential loan losses tied to the coronavirus pandemic.

Those events have led more industry observers to discuss whether it might be easier for the board to find a buyer than to try to address all of Berkshire's underlying issues.

“This management pivot could indicate that the company may consider partnering with another financial institution,” Jake Civiello, an analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott, wrote in a note to clients. “Certainly, this is not the only path. Regardless, the road ahead is loaded with formidable obstacles.”

Berkshire doesn’t have to sell, but it must make the case to investors that it has what it takes to stay independent, said Mark Fitzgibbon, an analyst at Piper Sandler.

“A big job for whoever takes over … will be to convince people that they’re on the right track, that [the new] CEO will be there for a while and the company will begin to execute and show results on its transition phase,” Fitzgibbon said.

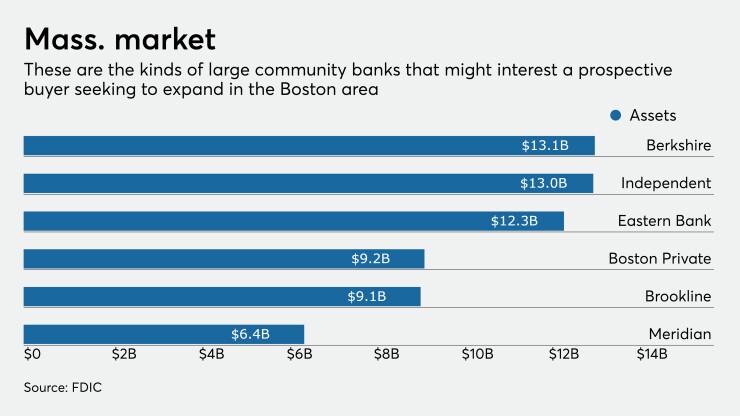

At the same time, it could be tough for Berkshire to find a buyer right now, Fitzgibbon said, given the "unprecedented and quirky time for bank M&A" and the company's sheer size, which includes more than 70 branches stretching from southern New Jersey to Vermont.

“It’s not like there are 100 banks that could buy it,” Fitzgibbon said.

A Berkshire spokesman declined to comment.

The next CEO could be Sean Gray, president and chief operating officer of Berkshire’s bank. He was named acting CEO and is a candidate to take over the post permanently.

While the $554 million goodwill charge was huge, industry observers said the bigger concern, and the most pressing challenge for Berkshire’s executives, is credit quality. The company has set aside $65 million this year in preparation for losses, largely tied to the coronavirus pandemic.

Berkshire said in a recent quarterly filing that criticized loans increased by 45% over the first half of 2020, to $340 million on June 30. About $1.5 billion in loans, or 16% of its total portfolio, were covered by three-month deferrals.

About three-fourths of Berkshire’s $260 million hotel book is operating under deferrals. Roughly 40% of leisure-related loans have been deferred, with most tied to Firestone Financial, a unit that focuses heavily on amusement parks, carnivals and fitness centers. Berkshire bought Firestone in 2015.

“Hospitality is the most sticky, and Firestone is probably the second most sticky, trying to get these companies back into their normal payment,” Marotta said during a July 30 call to discuss quarterly results.

Though deferrals in hard-hit industries were down from the first quarter, the company said in a recent regulatory filing that it “anticipates that measures of asset performance and quality will deteriorate in coming quarters based on its projections of credit losses on loans.”

Laurie Hunsicker, an analyst at Compass Point, said in a client note that she viewed Marotta’s departure “as a negative,” given his experience with credit risk, while warning that more heartburn is likely.

“We believe that [Berkshire] is substantially under-reserved,” Hunsicker added.

Fitzgibbon said he finds some comfort knowing that three former bank CEOs — Rheo Brouillard, J. Williar Dunleavy and Cornelius Mahoney — are on Berkshire’s board. Each ran banks that the company acquired.

Berkshire had been overhauling its operations after years of aggressive acquisitions under Marotta’s predecessor, Michael Daly, who stepped down in November 2018. Under Daly, Berkshire bought more than a dozen banks and nonbank lenders and got into businesses, like national mortgage lending and aircraft lending, that it

Bank acquisitions involving stock were also the main reason for the goodwill impairment charge.

Berkshire has also shuttered several branches and run off lower-yielding assets since Marotta become CEO. He also vowed to improve profitability and Berkshire’s culture. Among other initiatives, the company hired a former community organizer to oversee an ambitious diversity and inclusion effort. The bank also stepped up efforts to better reach underserved populations.

But the company’s ongoing strategic review and repositioning have “become more difficult to execute during the recent pandemic,” Collyn Gilbert, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, wrote in a note to clients.

“We believe the CEO change announcement is unlikely to inspire investor confidence that the balance sheet restructuring is complete,” Civiello said.

While it is unclear who will become Berkshire’s long-term CEO, industry experts were supportive of Gray, who joined the company in 2007 and succeeded Marotta as bank president when Daly left.

"We believe ... Gray's long-term experience at the company will ensure a smooth transition," Gilbert said.

Paul Davis contributed to this report.