What will drive bank lending

Population shifts and the explosion of

e-commerce will upend commercial real estate lending while heightened demand for clean energy, not to mention pressure from investors, will diminish banks’ enthusiasm for fossil-fuel financing.

By Alan Kline

Peter Minshall, a longtime real estate developer and investor in the Baltimore-Washington region, made a strategic decision five years ago to stop buying office buildings and invest in properties that are far less sexy: industrial warehouses.

Demand for office space has been shrinking rapidly as growth in the working-age population has slowed and advances in technology have allowed companies to digitize files that once took up lots of square footage. As Minshall sees it, the pace of this downsizing is only going to accelerate as firms eliminate support staff and permit — and even encourage — more employees to telecommute.

Companies “don’t need the volume of space they once needed to operate an office,” said Minshall, the managing partner at Washington Capitol Partners. “People don’t need to be in an office. They don’t need administrative assistants. They can do everything they need to do from a handheld device.”

This diminished need for office space is occurring as the explosion of e-commerce and cloud computing has led to soaring demand for warehouse space.

To fill all those online orders, retailers such as Amazon and W.B. Mason not only need acres of space by interstates, but also smaller facilities near population centers that allow for even speedier delivery. Meanwhile, businesses and governments have a seemingly endless demand for warehouses to store, process and distribute data.

This shift is poised to have a marked impact on banks given that commercial real estate lending is a key business line. Lenders will need to pay close attention to the various forces that will drive demand for CRE loans over the next five years and beyond.

Some of the same forces influencing demand for office and industrial space will impact other areas of commercial real estate as well, particularly housing and brick-and-mortar retail. Already strong demand for senior and multifamily housing will increase as baby boomers age and younger generations continue to migrate to urban markets, and the declining foot traffic at shopping malls and big-box centers is putting pressure on property owners — and their lenders — to come up with creative new uses for vacant retail space.

Banks also can expect expanded opportunities in renewable energy. Clean energy lending is already a fast-growing business and is likely to become a bigger part of banks’ portfolios in the coming years as more states and municipalities set clean energy targets and companies and households look to reduce their energy bills.

Andy Redinger, the head of the renewable energy group at KeyCorp, said that with solar power costs coming down, the biggest opportunity of all for banks over the next five years could be in financing rooftop solar projects.

Following is a look at some of the demographic, societal and technological shifts that could shape bank lending over the next several years, based on interviews with consultants, urban planners, bankers and other experts.

Aging baby boomers

The country is in the middle of an immense demographic shift in the workforce as waves of baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 start to retire.

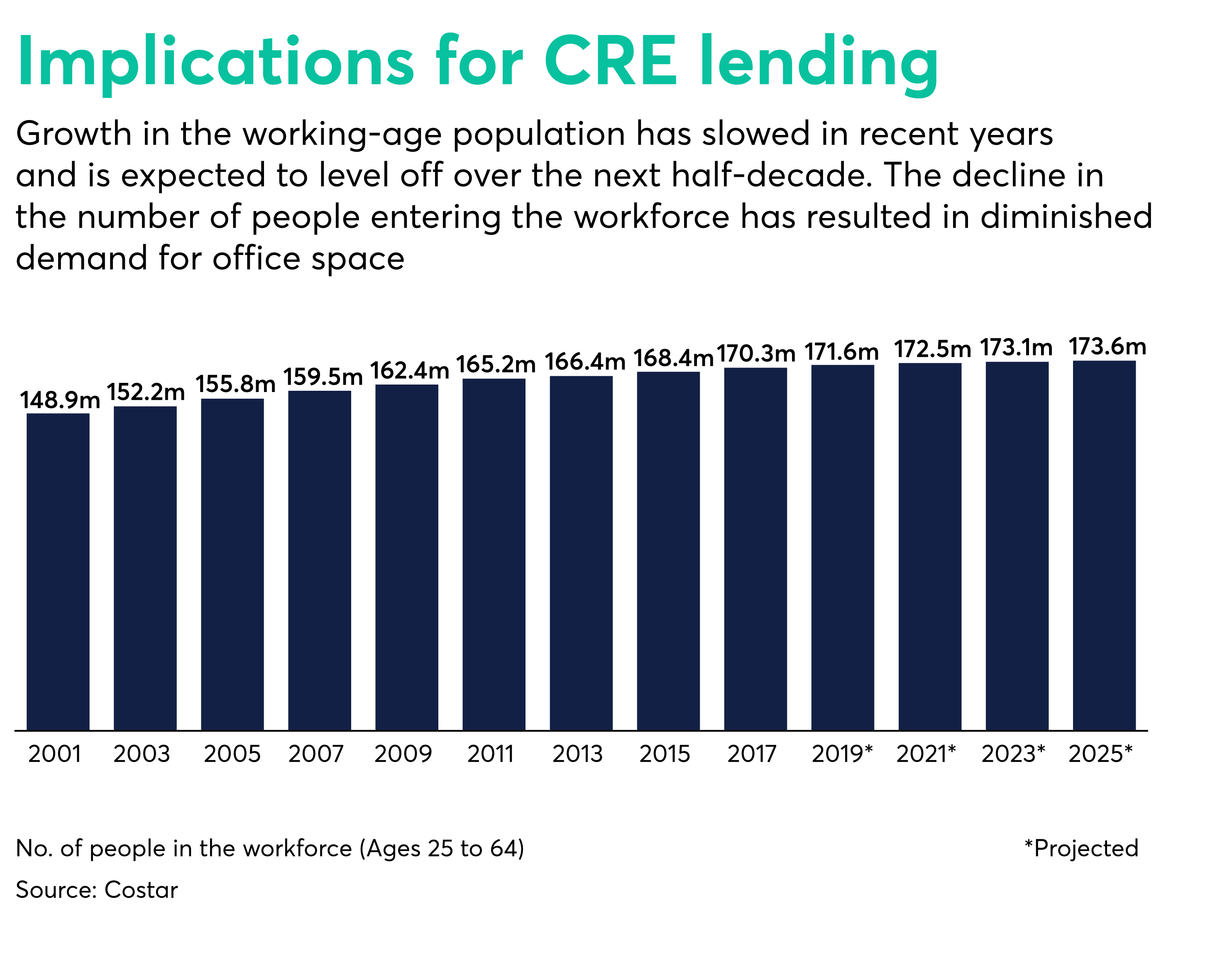

Over the last 10 years, the annual change in working age population growth has slowed considerably when compared to the previous two decades. That slowdown is expected to continue well into the 2020s, according to data compiled by the real estate data firm CoStar Group.

Between 1980 and 2009, annual growth in the working age population — defined as workers between the ages of 25 and 64 — was consistently between 1% and 2%, but the pace has slowed to an average of 0.6% per year over the past decade and is projected to be around 0.2% annually through 2027.

The reason for this slowdown is primarily because Generation X, which followed the baby boomers, is smaller. Add in structural shifts taking place across all industries and government agencies and it’s easy to see why demand for office space has been shrinking and will continue to decline through the next decade. At its peak in 2005, net absorption of office space totaled 170 million square feet, according to CoStar. Last year, total absorption fell to 100 million square feet.

Nancy Muscatello, a managing consultant at CoStar, said that demand for what known as “class A” office space in dense urban areas remains strong because firms see high-quality properties near public transportation and good eateries as crucial to attracting and retaining good employees. For banks, there is still significant opportunity to finance the construction and acquisition of these properties, Muscatello said.

At risk, she said, are older office buildings in urban markets that are becoming increasingly obsolete and suburban office properties that are far from public transportation and require workers to hop in their cars if they want to grab a decent lunch.

“Quality and location are becoming more and more important,” Muscatello said. “It doesn’t mean that the office market overall isn’t going to be performing well, but there are going to be sectors of the market that are going to perform better than others and are a better bet, especially in an environment of slowing demand.”

These trends won’t play out evenly across the country. Metropolitan markets with strong population growth, such as Austin, Texas, Orlando, Fla., and Raleigh, N.C., will have higher than average growth in the workforce and thus heightened demand for quality office space. The 10 fastest-growing U.S. metropolitan markets of the past decade are in just four states — Texas, Florida and the Carolinas, according to data provided by Gerald Bierling, a researcher at Generational Insights, a Mobile, Ala., consulting firm. The 10 slowest-growing markets are in the Northeast and upper Midwest.

The aging of the baby boomers is also expected to accelerate demand for both senior housing and multifamily rentals in urban locations. Many retirees, particularly the more affluent ones, are selling their suburban homes and moving into luxury apartments “and we see that trend continuing over the next five years,” Muscatello said.

Erika Poethig, a vice president and the chief innovation officer at the Urban Institute, said that for less-affluent seniors who want to remain in their homes, there will be an acute need for financing upgrades that will allow them to age in place. Think walk-in showers, outdoor wheelchair ramps and improved flooring and carpeting that can better prevent seniors from slipping.

Medicare does provide some grant money for such upgrades but not nearly enough to meet the demand, Poethig said. “Congress has appropriated very modest dollars for that, so there’s a huge issue around whether the housing stock is going to be equipped to be retrofitted and what the financing sources will be.”

The need for affordable housing

The chronic shortage of affordable housing in many urban markets is unlikely to abate anytime soon because there’s simply not enough supply to meet demand. Nationwide, there are only 31 affordable properties for every 100 extremely low-income renters, according to data from Mercy Housing, a Denver-based community development financial institution.

The shortage is not just in high-cost cities such as Washington, D.C., and Oakland, Calif., where gentrification is pricing out many residents, but also in faster-growing markets in Sun Belt states where housing costs are generally lower.

Muscatello said that in built-out markets, there could be a great opportunity for banks to finance acquisitions and conversions of older, obsolete office space into affordable multifamily units.

“That B and C product could be a driver for more workforce housing,” she said. “We’re already starting to see a lot of clients looking to acquire” those properties.

Poethig agreed that the older office buildings could be part of the solution, but said that in densely populated markets where acquisition costs tend to be high, developers and lenders will need a fair amount of support from governments — such as tax credits — to get projects done.

“More jobs are being created at the bottom part of the income [ladder] than the top, and it just costs more to build housing than that income group can afford,” she said. “In many markets there is always going to be a gap.”

In states such as Texas and Florida, the lack of supply is largely because there aren’t enough developers focusing on affordable housing, according to Poethig. Banks can help solve this problem by helping established affordable housing developers — typically nonprofits — expand into other cities. She sits on the board of Mercy Housing, which recently set up shop in Atlanta to identify development opportunities across the Southeast.

Banks “could provide lines of credit that will allow affordable housing providers to scale their capacity to grow into other markets,” she said.

The e-commerce effect

Brick-and-mortar retail will continue to face a reckoning as e-commerce sales surge, and lenders will need to work with property owners to find new uses for all that vacant retail space, said CoStar’s Muscatello.

Space that formerly housed electronics or sporting goods stores is already being converted into everything from fitness centers to megachurches. Muscatello said she sees the repurposing of retail space into health clinics and other service-oriented facilities as “a big opportunity” for property owners and the banks that lend to them.

The bigger opportunity, though, will be in financing the acquisition and development of warehouse space.

For decades, banks tended to steer clear of financing industrial projects because office and retail properties generated more consistent income streams and were seen as safer bets, according to Minshall of Washington Capitol Partners.

With e-commerce sales growing at around 15% a year and driving up demand for warehouses, that’s no longer the case. Warehouse space that was renting for $4 a square foot a decade ago is now fetching twice as much, giving banks far more confidence to finance construction of new projects, upgrades to existing properties and outright acquisitions. Average sales prices for warehouse space also have nearly doubled over the past decade, from $51.80 per square feet in 2009 to $97.30 in this year’s third quarter, according to data from CoStar.

“The dynamics of industrial are such that there’s plenty of opportunities for banks to make loans,” Minshall said.

He has been in the real estate business for 40 years and said that he sees the industrial market today “as the best investment opportunity of my career.” In the last few years, he has used bank financing to buy two old printing plants in the Baltimore-Washington corridor and repurpose them as distribution facilities for retailers.

“If I’m a banker, I’m not targeting office; I’m targeting industrial,” he said.

Minshall said that a looming threat to the warehouse market is a dwindling supply of land zoned for industrial use, especially as data centers continue to “muscle out other users.” In the United States, square footage devoted to data centers has grown by 25% over the past decade, to 230 million square feet, according to the real estate data firm CoStar, and that pace of growth is likely to continue.

But even in that potential shortage Minshall sees intriguing new possibilities for developers and lenders.

“What’s going to happen is that older assets are going to be torn down and sold for their land value, and new, bigger projects will go up,” he said. “It’s only a matter of time.”

A surge in renewable energy

Large and regional banks in recent years have become active in financing large-scale solar and wind projects and demand is only expected to increase.

To give a sense of the demand to come, Mark Haefele, the chief investment officer at UBS Global Wealth Management, pointed to the RE100, a group of 191 companies, including Apple and JPMorgan Chase, with a goal of getting 100% of their electricity from green sources (up from the current 39%).

Haefele said in a note to clients that reaching the target — just for that group alone — would require additional solar and wind capacity that is equivalent to Spain’s entire power generation.

And, he wrote, that would take an additional $100 billion of investment in renewable energy, based on an analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

By 2025, more banks will look beyond the big projects as well, to further expand their financing in areas such as energy storage, rooftop solar panels, indoor agriculture and electric vehicles, according to industry experts.

Alfred Griffin is the chief executive of NY Green Bank, a New York state-sponsored lender that works with private investors, including banks, to finance green projects. He said that demand for energy storage is expected to surge in the next couple of years as the cost of capturing solar energy for use during non-daylight hours comes down and battery technology improves. This presents considerable lending opportunities for banks with expertise in financing renewables.

“Certainly larger banks that have project financing teams are well aware of this and are paying close attention to it,” Griffin said.

For large solar projects of around 40 acres, batteries can be the size of two or three shipping containers and cost millions of dollars.

Any municipality or corporation that has set ambitious goals to reduce greenhouse emissions will need sufficient battery power to store energy that can be released when the sun isn’t shining, Griffin said. The state of New York, for example, has set a goal of receiving 70% of its energy from renewable sources within a decade and storage is expected to be part of that mix.

In an individual home with rooftop solar panels, a battery might be the size of a picture frame that sits on a wall in the garage. Financing for those smaller batteries can be rolled into rooftop solar installation, which is emerging as a sizable business.

KeyCorp's Redinger said that the bank is financing rooftop projects in two ways: partnering with contractors to provide point-of-sale loans to homeowners and providing working capital to solar providers that lease solar panels to homeowners. A typical solar installation costs around $25,000.

Redinger said that solar power is “starting to go mainstream” and that the demand is being driven largely by the potential for cost savings. With costs of generating solar power continuing to come down, demand is sure to go up over the next several years, he said.

“The residential solar business is growing 15% to 20% a year,” said Redinger. “There are 71 million homes in the U.S. and only 2 million that have solar panels on them. That’s just a massive, massive market.”

Griffin said that electric vehicles will become more mainstream in the next five years, presenting opportunities for banks to finance everything from charging stations to fleets of electrical cars and buses for businesses, municipalities and school systems.

NY Green Bank also has financed some indoor farming facilities, and Griffin said he expects more banks to follow suit as food producers look to cut costs and reduce their overall carbon emissions.

“If you are a resident of New York, your leafy greens are typically being shipped in trucks from California. Now technologies are available and efficiencies have been created so that those greens can be produced locally, are extremely high quality and will last longer in your refrigerator,” Griffin said.

Even as banks up their commitments to financing environmentally friendly projects, many still actively lend to oil and gas producers. But Griffin said he expects banks’ enthusiasm for fossil-fuel financing to wane over the next five years because there will be greater opportunities in renewable energy. According to the International Energy Agency, wind, solar and other forms of renewable power will attract about $322 billion of investment annually through 2025, almost triple what will go into fossil-fuel plants.

Big banks in particular, Griffin added, will be under heavy pressure from investors to do their part to slow the pace of global warming.

“It’s fair to say that a lot of the largest investors in the world, pension funds and so forth, are very focused on this,” Griffin said. “They want to see their investees having an impact on reducing greenhouse gases.”