Over the past year or so, many bankers, analysts and even some policy makers have downplayed the risks so-called leveraged loans pose to the banking system because, they say, it’s primarily hedge funds, insurance firms and other nonbank financial institutions making the bulk of them.

But reports from three regulatory agencies released in July show that leveraged loans on banks’ books have been rising steadily in recent years. Even if banks aren’t making the loans directly, the reports found, they are holding stakes in these loans either as participants in loan syndications or through collateralized loan obligations, which are composed of leveraged loans.

In its report released on July 30, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. also expressed concern that “leveraged loans have become increasingly risky… as lender protections have deteriorated” and that banks may be indirectly taking on more risk by providing loans to the nonbanks that issue corporate debt.

“Indirect exposures are opaque and could transmit stress from the corporate sector into the banking system,” the FDIC said in the report.

Taken together, the findings from the FDIC, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England would appear to challenge some policymakers’ claims that banks’ exposure to leveraged lending is minimal, said Mayra Rodríguez Valladares, a financial regulations consultant.

She pointed specifically to comments made by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell after a Federal Open Market Committee meeting in June, in which he said that the risk in leveraged lending “isn’t in the banks, it’s

“With all due respect, I was deeply troubled by [Powell’s] comment,” she said. “It’s just not true. The data tell a different story.”

Leveraged loans are credits issued to corporate borrowers that already hold high levels of debt, and frequently are rated as non-investment-grade borrowers.

The market for such loans has grown rapidly over the past decade as investors in search of higher yields have poured hundreds of billions into financing the loans, and lenders have offered more and more concessions to borrowers to win new business.

In the U.S. alone, lenders issued $816.4 billion of leveraged loans in 2018, compared with $721.4 billion in 2013 and $136.3 billion in 2008, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The

A number of congressional Democrats are worried that the loans could quickly go bad in a downturn, potentially triggering a recession. Republicans and executives at large financial institutions have argued that those concerns are overblown because financial firms, including banks, have built up substantial enough capital buffers to absorb losses.

Powell, speaking at

“Views [on leveraged lending] seem to range from ‘this is a rerun of the subprime mortgage crisis’ to ‘nothing to worry about here.’ At the moment, the truth is likely somewhere in the middle,” he said.

There’s also been widespread disagreement on the risk to banks, largely because there’s been scant data available. Moreover, each regulator uses different methodology to track leveraged lending, making it difficult to gauge banks' true exposure.

The report the Fed released on July 18 was the agency’s first-ever detailed analysis of the leveraged loan market.

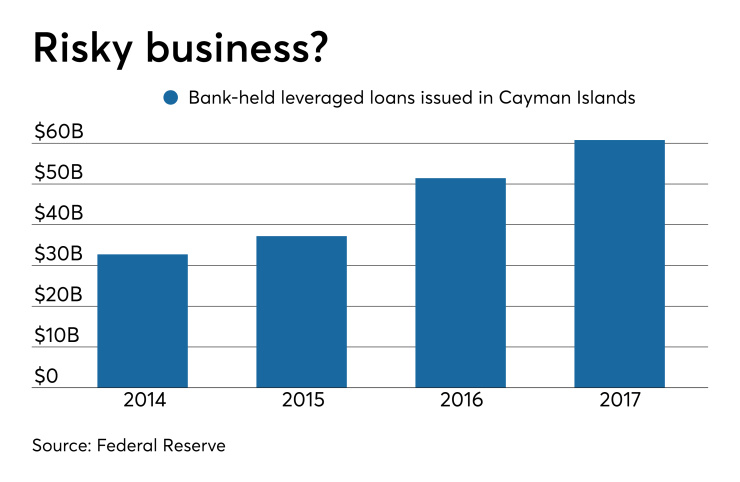

Analysts reviewed data from the Treasury International Capital System and Securities Industry Financial Markets Association “to quantify the full exposures of investors to the leveraged loan market” and found that banks’ holdings of leveraged loans and collateralized loan obligations more than doubled between the end of 2014 and the end of 2017, to $60.8 billion.

It also found that U.S. banks

The Bank of England and the FDIC spotlighted leveraged lending in reports released last month as well.

In its

And in its

The FDIC also pointed out that bank lending to nonbanks has increased by more than 600% since 2010, to $433.9 million, at March 31. Most of those loans are to nonbank mortgage lenders, but the FDIC also expressed concern that some loans are going to nonbanks that make higher-risk corporate loans.

Several industry experts say that while banks’ exposure to leveraged lending may be increasing, the risk remains minimal because banks are providing the least risky portion of the financing. Nonbank lenders, by contrast, seek the highest yields and thus hold the most risk, said Richard Farley, a corporate lawyer who has advised borrowers on billions of dollars’ worth of leveraged loans from both banks and nonbank lenders.

“Virtually all the turmoil is with nonbank lenders,” said Farley, chairman of the leveraged finance group at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel.

Analysts agree that banks are insulated from the riskiest portions of the credits.

“On their leveraged loans held for sale, banks have built in more protections for themselves,” said Brian Foran, an analyst at Autonomous Research. And on banks’ holdings of CLOs, banks typically own the lowest-risk tranches of those securities, Foran said.

Still, analysts say leveraged lending is a touchy subject with bankers these days.

“Leveraged lending is kind of a negative word in the industry right now,” said Brian Kleinhanzl at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “Bankers try to downplay it as much as possible.”

Indeed, when asked about leveraged lending, many bankers will say that the loans represent only a tiny portion of total assets, or that they’re in the process of getting rid of much of what they do have.

The $169 billion-asset Fifth Third Bancorp in Cincinnati, for example, has reduced the size of its leveraged book by 55% since 2015, Chairman and CEO Greg Carmichael said at a March investor conference.

“We really looked for what type of lender we want to be in this space, who we want to lend to, what type of clients we’re looking for and what type of exposure we think is reasonable,” Carmichael said.

When the $12 billion-asset WSFS Financial in Wilmington, Del., acquired Beneficial Bank in Philadelphia earlier this year, it immediately said it would cap the leveraged-loan portfolio it inherited from Beneficial at $150 million.

The $30 billion-asset Texas Capital Bancshares has reduced its leveraged book by 13% since the end of 2018, when

CEO Keith Cargill said in an interview that Texas Capital looks at leveraged lending opportunities on a case-by-case basis.

It has, for example, tapped the brakes on making leveraged loans to private equity firms that use funds to acquire companies because Cargill believes the acquired companies are overvalued.

“The valuations have gone up … it’s just the type of thing that gives us pause when you get late in an economic expansion,” Cargill said.

But the Dallas bank isn’t exiting the space entirely. During the second quarter, it picked up what Cargill called “one of the best leveraged loans we’ve had in 20 years.”

Cargill added that by scaling back its leveraged lending now, Texas Capital will be well-positioned to enter the market more aggressively when the economy cools and valuations are more reasonable.

“We should be in a great position to exploit that economic upturn when there are more appropriate valuations,” he said.