Banks may be hoping for a friendlier enforcement environment under the Trump administration, but legal experts suggest a lighter touch will probably not extend to Wells Fargo for the ongoing scandal tied to the bank's sales practices.

As the bank

Wells was expected to be the first major test of Obama-era guidelines to hold high-level executives accountable for corporate wrongdoing, but it was unclear if Attorney General Jeff Sessions would continue the policy to crack down on both individuals and companies. The

Observers said they have seen no sign of the Justice Department reversing course. (Attorneys said it likely will take another six to eight months for Justice to resolve its investigation.)

"They'll hit Wells Fargo hard. They have to because it's a high-profile case and there are too many people invested in it already," said Michael Volkov, a former federal prosecutor and veteran white-collar defense attorney who is a principal at Volkov Group in Del Mar, Calif. "They are going to work their way up and they are going to try to get as high as they can."

A DOJ investigation of Wells executives would apply even more pressure on the former executives at the heart of the scandal, including former CEO John Stumpf and his former retail banking head, Carrie Tolstedt.

Stumpf initially blamed employees for the sales practices, and his efforts to try to explain to lawmakers how the bank's employees were pressured to open unauthorized accounts were largely panned. Tolstedt oversaw the unit in which 5,300 employees were fired over a five-year period for opening 1.5 million deposit accounts and 565,000 credit card accounts without customers' knowledge.

Any federal charges or sanctions against Wells and top executives would depend on a wide range of factors, including when the company and individuals first were apprised of the misconduct and what actions were taken to remediate customers, train employees and put the issue on the company's audit watch list.

Legal experts say any executives fired as a result of the scandal could be in the Justice Department's crosshairs.

Four Wells executives have been fired since the cross-selling practices came to light. They include Shelley Freeman, a former regional president in Los Angeles who later headed consumer credit solutions; Pamela Conboy, Arizona lead regional president; Matthew Raphaelson, head of community banking strategy and initiatives; and Claudia Russ Anderson, the former chief risk officer of community banking. Several other executives have been demoted. Meanwhile, the internal Wells report released Monday basically confirmed that Tolstedt had been let go because of the scandal.

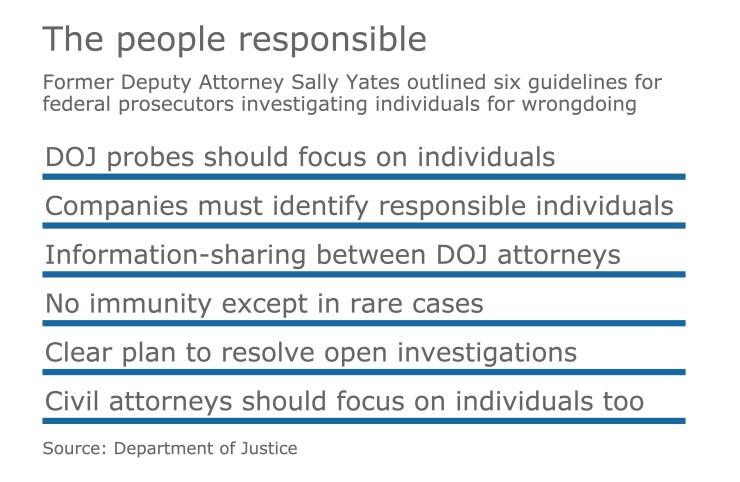

In the years after the financial crisis, the Justice Department was roundly criticized for failing to hold any high-level executives accountable. Somewhat in response, the so-called

Despite the industry's hopes that the new administration will ease up on Obama-era enforcement policies, the directive on investigating individuals appears to still be in play.

“The Yates memo in some form will survive the transition to the Sessions DOJ,” said Joe Whitley, chairman of the government enforcement and investigations group at Baker Donelson and a former acting associate attorney general at the Justice Department.

Justice Department spokesman Peter Carr confirmed in an email that "the Yates memo remains in effect and is the department's current policy." (Wells declined to comment for this story.)

Still, former prosecutors cautioned that it is tough it is to trace wrongdoing to top executives.

“It is not easy to make a case against an individual in a corporate context because individuals act through committees, responsibility is diffused, individuals leave over time and it becomes a very case-specific endeavor,” said Ronald H. Levine, chairman of the internal investigations and white-collar defense group at Post & Schell and a former chief of the criminal division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Philadelphia.

The Justice Department has always considered holding corporations and individuals accountable, but the Yates memo marked a significant change internally that will have an impact on the Wells case, Levine said.

Before the Yates memo, prosecutors had to get a release from a U.S. attorney to justify the prosecution of an individual. Now, prosecutors have to get a release if they choose not to prosecute an individual, Levine said.

"At the end of the day, prosecutors are making a 'good guy-bad guy' judgment and they are looking at mitigating factors like [whether a company has] a robust audit and compliance program or the employee was rogue," Levine said. "And aggravating factors go the other way, if there is conduct that wasn't stopped."

Prosecutors are required to build cases against high-level executives from the onset, without providing immunity. In addition, companies like Wells are only eligible for credit if they cooperate by identifying all the individuals involved in or responsible for the misconduct regardless of their position, status or seniority. According to some legal sources, if a company just identifies some names of those involved — while leaving out other individuals — that is not considered cooperating with prosecutors.

"Wells has emails and reports and complaints coming in including from whistleblowers, so [Justice] will be trying to flip some people and get as high up as they can in this case," Volkov said. "They are going to have to offer up, either through outside or corporate counsel, and turn over individuals with criminal cases to bring."

The Justice Department could bring either civil or criminal charges against Wells and high-ranking executives. A key issue in the government’s investigation will be whether Wells is offered a deferred-prosecution agreement, where the company pays a fine but does not admit guilt and escapes a criminal indictment, said Rena Steinzor, a law professor at the University of Maryland.

Such deals have baggage. They were an example of the government’s response to financial crisis-era activities that critics said was too lenient.

“Deferred-prosecution agreements were very controversial under Obama,” Steinzor said, noting that “there was an uproar on Capitol Hill” when former Attorney General Eric Holder famously said some banks were “too big to jail.”

The Wells investigation will be a “bellwether case” on how serious the new administration is in pursuing financial companies and executives, Steinzor added.

Some observers said they were not surprised that the Justice Department has continued the investigation unaffected by the change in administration.

Decisions about when, how or whom to prosecute should not vary greatly from one administration to another because Justice pursues cases independent of politics, said Sara Lord, a partner at Arnall Golden Gregory LLP and a former New York assistant U.S. attorney.

“The Yates memo puts a premium on cooperation especially in the form of providing all relevant information,” Lord said. “That’s the $64,000 question: How do you define relevant information? It puts the judgment call in the hands of" the Justice Department.

The phony-accounts scandal exploded last year with regulatory fines against the company and embarrassing congressional hearings for senior executives. The Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office conducted an 18-month investigation after Los Angeles Times reporter E. Scott Reckard broke the story about the bogus accounts in 2013.

Since then, Wells has refunded $3.3 million to customers, and last month it agreed to pay $110 million to settle a class action lawsuit brought by customers who accused the bank of opening unauthorized accounts.

Although the company is trying to put the scandal behind it, several investigations are being made public, including over whether the bank wrongfully fired whistleblowers who helped bring the scandal to light. Last week, the Labor Department ordered Wells to pay a former wealth manager $5.4 million in back wages and reinstate him. Wells has also been told by the Labor Department to