Shortly after Wells Fargo & Co. announced its goals for revenue growth and return on assets at its inaugural investor day last week, Chief Financial Officer Howard Atkins joked that audience reaction had already proved the company's targets were right.

Half the attendees thought a target of 10% revenue growth and a 1.5% return on assets were too low, he said, the other half too high.

Another read: That half of a crowd composed of Wells' own shareholders doubted the plausibility of the targets suggests that those targets are extraordinarily ambitious.

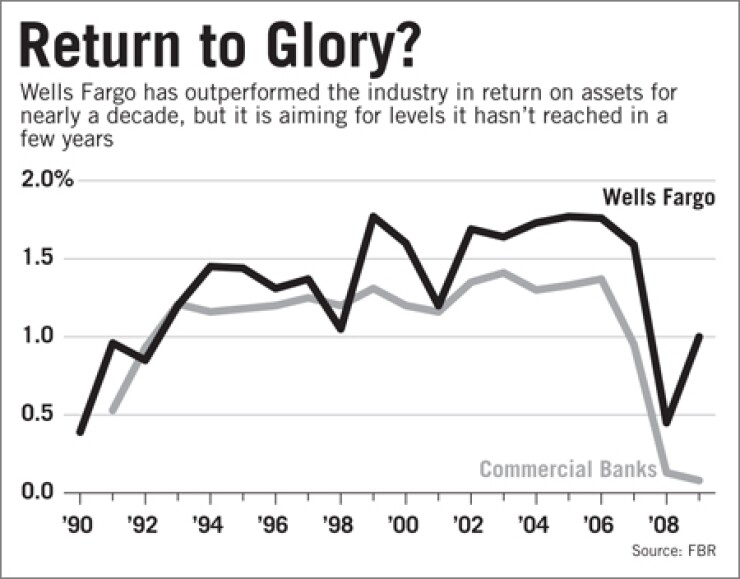

For the last two decades Wells has thrived by combining rapid-fire acquisitions with an impressive ability to sell its retail customer base more products than other banks could. Now it is betting it can wring the same results out of commercial banking, and on a nationwide scale. Wells' admittedly "aspirational" targets aren't just well above the industry's long-term average. They are numbers that Wells itself didn't consistently hit before the boom years of the last decade.

"They have a chance to increase revenue in an outsized proportion to the rest of the industry," said Tony Plath, a finance professor at the University of North Carolina's Belk College of Business. "But 10% revenue growth and 1.5% ROA? The physics of banking just don't suggest that's going to happen."

Indeed, economic growth remains stagnant, deleveraging could drag on for years, and regulatory threats to the banking industry are too numerous to mention. On top of that is a series of unfortunate coast-to-coast banking precedents: as Plath noted, no bank to adopt a nationwide model has gone through a full business cycle without a blow-up from excessive risk.

As credit losses have eased, how Wells will avoid that fate has become the implicit subtext of its public appearances. The company's solution is simple, bordering on trite. It intends to focus on its customers.

In every industry, there are companies that succeed by fanatically pursuing goals to which competitors pay lip service but never quite pull off. Think Wal-Mart Inc. and low prices. Apple and user-friendly design. Or what Wells is trying to do with its "cross-sell culture."

"Listen carefully, because that's where our growth is going to come from," Atkins told investors.

There's evidence that Wells is already making that approach work on the retail banking side. The average number of products held by Wachovia's customer base (currently 4.85) is rising at a 9% annualized rate, faster than products-per-customer growth among Wells' legacy customers, who currently have six products apiece. Maintaining that edge on retail — along with Wells' extremely high ratio of checking accounts to time deposits — is essential to the bank's net interest margin, and therefore its return on assets.

Transferring that same talent to Wachovia business lines was a challenge Wells' management acknowledged. Carlos Evans, a investment banking executive who joined Wells from Wachovia, said that the same growth would be possible given the sheer size of the two banks' combined commercial customer base — and, of course, Wells' genius for cross-selling.

"The reporting capabilities that we have become the beneficiaries of are incredible," Evans said, and "far more advanced than what we had access to at Wachovia."

Similar expectations are built into the plans of David Carroll's wealth, brokerage and retirement unit, which aims to produce up to 25% of Wells' revenue, up from 14% now. In an investor day presentation, Carroll cited plenty of reasons for Wells' optimism, from demographic trends to expected consolidation in the industry.

But underlying everything once again was the cross-selling.

Cooperation with his new colleagues' business units generated $400 million in new revenue last year, Carroll said, "and we believe that number clearly should be more towards $1 billion as markets recover."

If cross-selling is Wells' answer for revenue (and especially, fee income), it's also crucial to the company's intended conservatism in lending and investments.

Paul Miller, a senior analyst for FBR Capital Markets who attended the conference, pointed out that banks that adopted a coast-to-coast model often reweighted their balance sheet to compensate for decreased operational efficiency. "It's very difficult to keep that expense line in check, when you have a far-reaching system," he said. "What that results in is that you start stretching on risk."

So far there's been no sign of that with Wells, Miller said. It bank has been stockpiling cash in short-term investments to avoid interest rate risk, and Wells' current operating income is impressive. If it can reduce chargeoffs to around 1% of average loans from its current 2.7% — a potential savings of about $3.3 billion from the last quarter — it would top a 1.5% ROA if operating income remained flat.

Given that coast-to-coast banks sometimes fell short of that mark during the heady years of the credit boom, that might be more difficult than it appears. And assuming that Wells can maintain the stellar post-crisis performance of certain divisions — the bank's $12 billion mortgage servicing gain last year comes to mind — may be a reach barring an exceptionally robust economic recovery.

"Wells has enough reserves in their balance sheet at this point to overcome a lot of negativity for the time being," Miller said. But for Wells to hit its targets for an extended period, "You need loan demand, you need pricing power, you need to be able to get higher interest rates," Miller said. "You can't do it through fee-income growth."