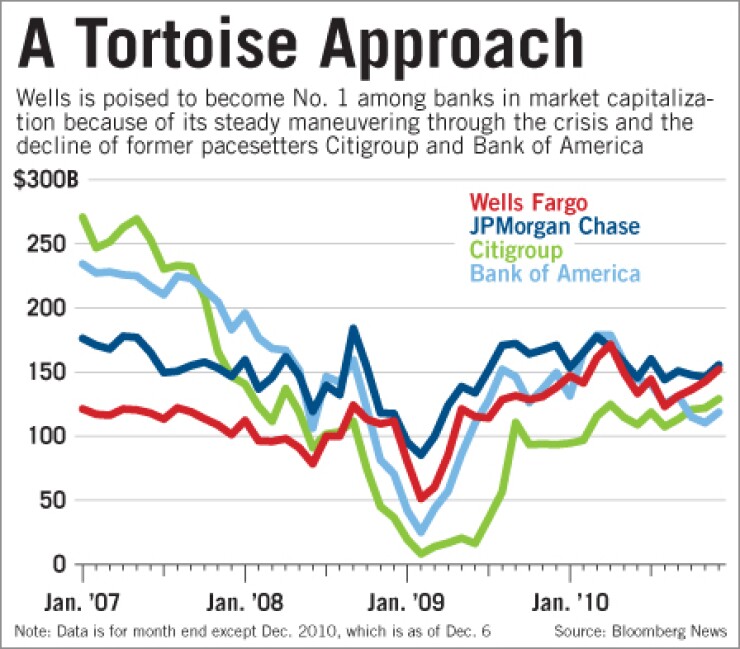

For whatever it's worth, Wells Fargo & Co. may soon be the most valuable bank in America.

After the company's stock rose 5% over the last two weeks, Wells is within a few billion dollars of JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s $156 billion market capitalization.

But don't expect the company to throw itself a party should it overtake its rival in the next new few weeks — while better than its peers, its average total annual return over the last decade was only 4.4%. Wells has created sector-beating value for its shareholders, but its near-first-place capitalization is due primarily to the failings of its larger competitors and its relative distaste for capital markets.

To be sure, the bank's trajectory is a reminder that Wells enjoyed relative prosperity during the financial crisis. It gained a national retail banking network, a capital markets group and an asset management business from Wachovia Corp., and it posts the best cross-selling and funding-cost numbers of its peer group. It has done a relatively good job at minimizing the fallout of mortgage put-backs, robo-signing notoriety and other industry missteps.

"They deserve to be praised for this," said Paul Miller, managing director of FBR Capital Markets, though he noted that the bar for large-bank outperformance is low.

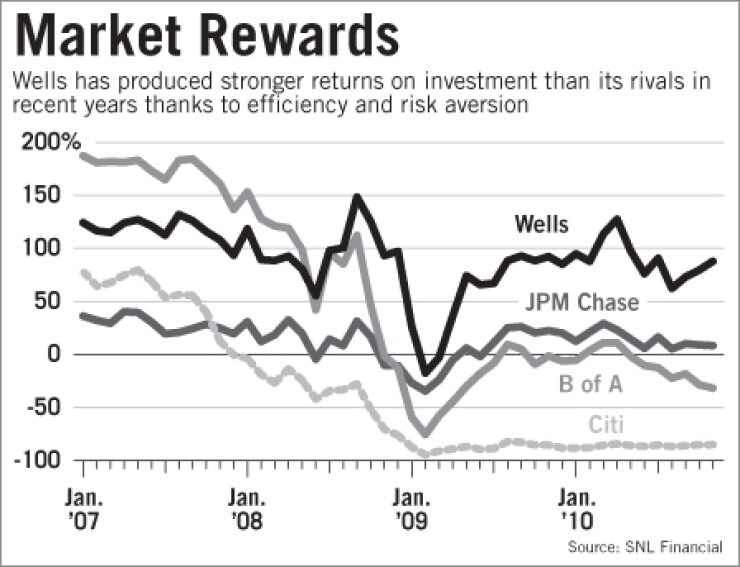

Data from SNL Financial shows that over the last decade the universe of banks the company tracks has produced an aggregate total return of negative-7%, worse than any major index.

For investors in the banking giants, the clobbering has generally been worse. While JPMorgan Chase has appreciated an average of 3.3% a year over the last decade, Bank of America's total returns have been negative-2.2% a year. As for Citigroup Inc. stock — well, an investor who gave the company a dollar 10 years ago now has 16 cents.

It is only because of such capital destruction, in fact, that Wells has been able to take the lead in market cap. Through a modest annual total return and a few business combinations, the once $76 billion lightweight has turned into a $151 billion institution. While it still is well behind B of A, JPMorgan Chase and Citi in asset size, investors have rewarded Wells for the efficiency of its operations, and for its reduced reliance on capital market operations.

"Capital markets activities are the lowest valued in a price-to-earnings sense that a bank can engage in," said independent analyst Nancy Bush of NAB research. Investors historically have not viewed trading income as reliable, a bias that only grew stronger during the financial crisis.

"[JPMorgan Chase CEO] Jamie Dimon has chosen a specific and very tricky course, which is that he's going to grow as a consumer bank, but he's also putting his faith in growth in capital markets," Bush said. "I want to ram my head against the wall when these guys start saying they want to grow capital markets."

Wells executives, meanwhile, have made it clear that "they are commercial bankers first and foremost," Bush said. "And that is the key to them catching up to JPMorgan."

But Bush and Miller said they did not see Wells' recent market-cap surge as a sign that the clouds over big banks were beginning to lift.

"Something has got to happen to this industry to get us to a position where shareholders can be a bit more sure that you're not going to have five good years for a stock and five years of it exploding," Bush said.

Miller, meanwhile, suggested that investors have become jaded with the biggest names in the banking industry.

"It doesn't get the growth guys and the value guys are losing patience," he said, adding that the twin problems of low growth and high regulation meant that room for differentiation among banks was slim.

There is no doubt that Wells — along with U.S. Bancorp, PNC Financial Services Group Inc. and BB&T Corp. — emerged from the financial crisis in a better position than their competitors, Miller said. But that doesn't mean that the competition will be any less grueling.

"It's all the same model. You take in cheap deposits, underwrite mortgages and garner some fees in between," Miller said. "You can see [those banks] have the advantage, but in a shrinking environment, who cares?"