One of the main spigots of cash the Federal Reserve opened to fight the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, has delivered only a relative trickle of financing.

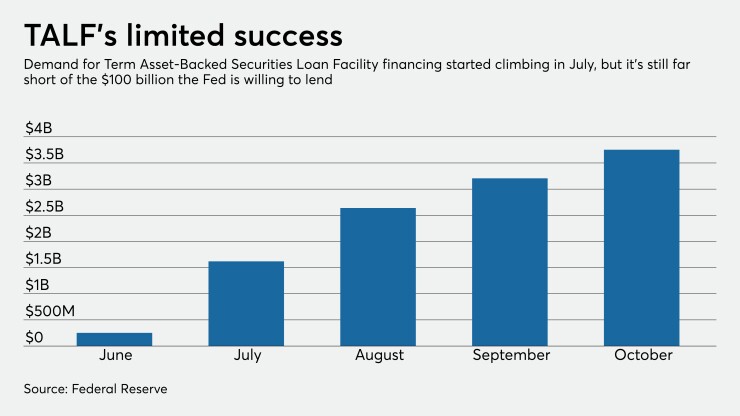

As of the end of October, the Fed had funneled about $3.7 billion in loans through TALF to bond investors at rock-bottom rates, a fraction of the $100 billion the central bank had committed. Narrowing spreads have made the program less lucrative than expected, limiting participation to a handful of investors. With TALF set to expire at year-end, it seems likely to be shelved, right?

Hold on, say policy experts who argue the program has had some less noticeable — but real — stabilizing effects on secondary markets in general. With the sharp rise in new COVID-19 cases this fall, those observers and funds participating in TALF are urging policymakers to extend the program into 2021.

"Because the market did find its footing before TALF became operational, the economics are borderline for the deals in TALF,” said Kristi Leo, president of Structured Finance Association, which represents a variety of participants in the bond markets. Yet “it really gave a backstop and some confidence to the market."

Investors participating in TALF use the program’s cheap financing to buy securities backed by commercial mortgages and loans to small businesses, students and a variety of others. The idea was to provide a backstop to the market so that money would continue flowing through these investment companies to lenders that provided badly needed credit as social-distancing measures went into effect and businesses shuttered.

Scores of investment firms began building up special investment funds to jump into the program. Many of them had netted massive profits from the original TALF in the 2008 financial crisis by scraping up the difference in what the risky subprime mortgage bonds yielded and the rate the firms had to pay on the Fed loans.

However, 79% of the program’s loans this time around have landed at just two investment firms: Belstar Management Company and MacKay Shields. The reason can be found in a key indicator in the securities market that started to wobble in early March as the pandemic unfolded.

The credit spread on triple-A-rated commercial mortgage-backed securities, which is the difference in interest offered to investors to buy the bonds compared to what they would gain from ultrasafe Treasuries, began spiking around March 12, according to research from Neuberger Berman. Higher spreads are a sign of rising risk that bond investors want to be paid a premium to shoulder.

The spread climbed from below a 50 basis-point difference in the middle of March to almost 350 basis points by the time the Fed announced there would be a new round of TALF on March 23 along with a menu of other stimulus measures.

But before the Fed could publish the specifics of the program like which securities would qualify for purchase by participating investors, in April, spreads on highly-rated CMBS had settled back to about 200 basis points by that point and have deflated since. That’s the calming effect experts have pointed to.

"A lot of folks were raising money and ultimately decided not to go through with their fund as spreads came in when the program was launched,” Leo said.

Matthew Hays, who leads the asset-backed securitization team at the law firm Dechert, said some private funds are keeping “some powder dry” to participate in the program if it’s needed to steady markets again because of the recent rise in COVID-19 cases.

"When spreads came down earlier this spring, it wasn’t because TALF was available — it was because it was announced,” Hays said. "The potential is fairly strong still that we see an extension. If there isn’t a stimulus package at all, that may create tension in the market, but it’s unclear right now."

Credit spreads on other kinds of lower-rated securities, like those backed by properties that have gone vacant during the pandemic, have ticked up to their highest point since the last financial crisis,

MacKay Shields has taken more than $837 million in TALF loans through a special fund designed for the program, according to Fed data. It has used the funding to buy CMBS issued by several large banks and other securities backed by Small Business Administration loans and student debt issued by Navient.

"Our investment thesis was that TALF 2.0 would be fairly different from TALF 1.0,” said Stephen Cianci, co-head of the global fixed-income team at MacKay Shields. “We were very measured in the size of the program we were offering to clients. We kept the program rather small. We believe that larger sizes would dilute the potential for [returns].”

Extending TALF into 2021, while lengthening the time the market can operate with a backstop, could also serve fund managers that went through the costly process of putting a fund together to take advantage of the program and are trying to deploy the capital before the deadline.

“People will try to ensure that the money they put into these funds are deployed,” Leo said. “People have been watching that very closely."

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said at a Nov. 5 press conference following a Federal Open Market Committee meeting that policymakers, including those at the Treasury Department, were “just now turning to that question” of whether to extend the programs, including TALF.

Cianci said when the Fed announced an extension of TALF from its original expiration date in September to the end of the year, it was a kind of insurance policy if there was a new wave of COVID-19 cases or if the presidential election proved difficult.

"There is a likelihood of a potential extension,” Cianci said, adding, “we are not banking on that potential extension.”