Colin Walsh always planned to do things differently than most fintech startups. The Varo Money CEO had a strategy to outcompete incumbent banks for customers who live paycheck to paycheck, and it involved becoming a bank rather than challenging the system from the outside.

The approval process took more than three years, and it required an upfront investment of

“So we did it the opposite way than your typical Silicon Valley playbook,” he said. “A Silicon Valley playbook is, just grow at all costs, build something really basic, scale it up as quickly as you can, and then go figure out how you're going to turn it into a sustainable business sometime in the future.”

Ten months after Varo Bank

Though Varo Bank’s revenues rose by nearly 50% between the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of this year, they were still dwarfed by expenses. In the first three quarters that the bank filed public reports on its financial condition, its net losses totaled roughly $110 million. Varo also recently weathered an operational issue that left some customers disgruntled.

Regulators expect any newly approved bank to turn profitable within three years, Walsh noted. “And we’re very much on track for that,” he said.

Walsh is an industry veteran who — before founding San Francisco-based Varo Money in 2015 — had done stints at American Express and the British bank Lloyds. The company’s chief financial officer, chief risk officer, product chief and general counsel are also experienced bankers.

All told, the company has raised nearly $500 million, led initially by the private-equity firm Warburg Pincus. A substantial percentage of that money has gone to capitalizing the bank. When the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. approved Varo’s application for deposit insurance last year, it ordered initial paid-in capital of at least $104.4 million. Varo is currently the best-capitalized bank in the United States, Walsh said, with a sky-high Tier 1 capital ratio of 62.7%.

That hefty base of capital may help Varo endure early losses that are large even in comparison with other startup banks. Last year, Varo reported a return on equity of -63.8% and a return on assets of -19.7%; both figures were the lowest among the 30 U.S. banks that have opened since May 2018, according to a review of call report data.

Varo, which for years offered deposit accounts in partnership with the Bancorp Bank, is just starting to introduce credit products. The product expansion figures to create new revenue streams. In the first quarter, Varo reported net interest income of just $173,000.

“Regulators are very close to the business and how it’s evolving,” Walsh said. “And the economics are evolving very nicely, and in line with what we expect of our business plan.”

The typical de novo bank has historically started making a monthly profit after 18 to 33 months, with the average being around 27 months, said Ed Carpenter, chairman and CEO of the bank advisory firm Carpenter & Co.

The growth of Varo Bank, which had $403 million of assets at the end of the first quarter, has likely been constrained by the demands of bank regulators. “Regulators get very nervous about vigorous growth in the de novo period,” said Michele Alt, a co-founder of the financial services advisory firm Klaros Group.

She added that when regulators see aggressive growth projections at a startup bank, they want to know whether the plans are realistic and whether the bank has the necessary risk controls in place.

Walsh said that Varo is getting ready to accelerate its growth now that it has established the proper controls. “But we think Varo could get very large over these next several years,” he said.

One way that the bank could accelerate its growth is by spending more money on marketing. Varo recently hired Carolyn Feinstein, who previously led marketing at the file-hosting service Dropbox and the video game company Electronic Arts, to lead its efforts in that area.

Varo, which uses the tagline “A bank for all of us,” recently started its first national brand campaign. Walsh acknowledged that the vast majority of Americans have never heard of his company.

“If you ask, who would you consider for a digital bank, only about 7% of the population would know to ask about Varo,” he said. “But that means that 93% of the people in this country don’t even know who we are. So the opportunity, now that we’ve invested in creating a profitable business model, to be able to scale that with a better product offering, is enormous.”

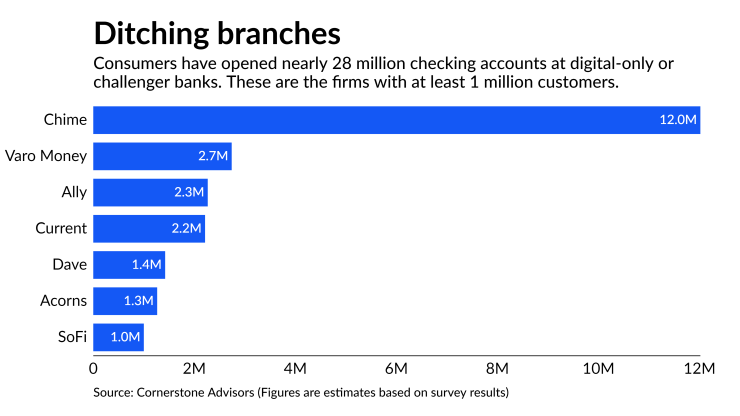

Varo has an estimated 2.7 million U.S. checking account customers, compared with around 12 million for Chime, according to survey data from Cornerstone Advisors. San Francisco-based Chime, which has not pursued a bank charter, has spent heavily on marketing, including a multiyear deal with the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks that put a Chime patch on players’ jerseys.

“Varo made the decision to go after the banking license, and my guess is that probably diverted resources from keeping up with Chime’s marketing budget,” said Ron Shevlin, Cornerstone’s director of research.

Varo is targeting a similar market segment as Chime. Walsh described the audience as the roughly 130 million Americans who are “financially coping” — a term coined by the nonprofit Financial Health Network to describe people who are struggling with some aspects of their financial lives, and are less well-off than the “financially healthy” but doing better than the “financially vulnerable.” He added that a disproportionate percentage of the company's customer base is African American or Latino.

Varo is trying to build its products around the needs of its target consumers. It does not charge overdraft fees, but it does have a product called Varo Advance that allows qualified customers to get cash advances of up to $100. Advances of $20 are free, while larger ones currently cost $3 to $5.

The company has also started rolling out Varo Believe, which it bills as a credit-building product, and which has some similarities to a secured credit card. Instead of putting down a security deposit upfront, to provide protection against the possibility that the funds will not be repaid, Varo sets aside money from the user’s bank account into a so-called vault account, which is then used to pay off the bill in full each month.

“This is a credit card that works like a debit card,” said Todd Baker, a senior fellow at Columbia Business School’s Richman Center for Business, Law and Public Policy and the managing principal of Broadmoor Consulting.

The product works from a business standpoint because Varo is able to collect the higher interchange fees that get charged when a consumer uses a credit card, as opposed to the lower fees charged on debit-card purchases, he said.

Walsh confirmed that Varo will receive the credit card interchange rates on the product but said that the fee revenue is not the company’s primary motivation.

“The real advantage for us is that it helps customers improve their credit. And then we think about the whole life cycle, and being able to do more with those customers over time, in terms of being able to provide them access to other credit products. And so it’s really an entry product that allows us to build a relationship with the customer,” he said.

Other products on Varo’s road map include joint and family accounts, and certain investment options.

A number of consumers recently lashed out at the company online for closing their accounts unexpectedly and without a clear explanation.

Matt Oberdick of Oklahoma City said that he had been a Varo customer for less than a year when he recently received a notice stating that his account was being closed. He started a Facebook group that attracted the attention of other Varo customers who had similar experiences and were waiting to receive their funds.

Oberdick and numerous other affected Varo customers eventually got their money back. Some of them received messages from Varo stating that their accounts had been closed in error. In those messages, the company said that it would send the customer an additional $100 check due to any frustration the situation may have caused.

When asked in late April about the account closures, Walsh called it a one-off instance involving suspected fraud, but he did not explain what went wrong. “Those accounts have all received their checks,” he said. “And it didn’t affect that many people, but they were quite vocal obviously.”

“That is definitely not something that is an ongoing or recurring pattern,” he said.

Varo said in a written statement that it cannot comment on the closures of specific customers’ accounts, citing legal obligations and customer privacy considerations.

“Accounts are closed periodically as the specific circumstances warrant — there’s no seasonality or pattern to account closures. Typically it occurs for a fraud risk or other financial crime risk reason,” the company’s statement read.

Because Varo operates without a branch network, it has some structural advantages over the banks from which it hopes to poach customers.

“We’re able to profitably serve, as we scale, huge segments of the population that the banks really struggle to be able to serve, because the economics simply don’t work,” Walsh said.

Being a bank also offers the company certain advantages over other digital upstarts. For one, it can freely call itself a bank, conjuring up safety and security in the minds of consumers, without tripping the kind of compliance issues that

Walsh said that becoming a bank was meant to give Varo a sustainable business model and a long-term strategic advantage. “And now that we’ve kind of crossed that bridge, it’s really becoming very evident,” he said.