When U.S. Bancorp decided it needed to make sure emergency loans reached the smallest of small businesses, especially those owned by Black Americans, executives knew exactly which organizations they needed to work with to help make that happen — community development financial institutions.

Banks have long partnered with CDFIs, but executives say the nonprofit financial institutions will play an increasingly critical role in newer efforts to broaden outreach to minority small businesses. Prompted by recent civil unrest and systemic issues made worse by the pandemic, banks are reflecting more critically upon their own role in contributing to those unequal systems — and they’re opening their checkbooks.

“Being a superregional bank affords us to cover a lot of ground, but it doesn’t cover all of the ground,” said Bill Carson, a business development officer at U.S. Bancorp Community Development Corp., the company’s community investment and tax credit subsidiary.

“We don’t have the level of expertise that [CDFIs] have in knowing the ins and outs of businesses … and communities and organizations,” said Carson, who leads the development arm’s New Markets Tax Credit investments in the Southeast. “We can’t possibly know as much as they do, so we really rely on our CDFI partners as much as they rely on us to deliver the types of direct benefits to communities that we are not able to deliver.”

The pressure is on for big banks to help foster systemic change. Following June protests nationwide over the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, a number of big banks collectively pledged billions to address racial injustice. Big-dollar commitments

Banks are also reexamining the diversity of their vendor relationships and seeking to match entrepreneurs with vital resources, such as shared workspaces or technical assistance.

A budding partnership

As part of its early pandemic response, the $543 billion-asset U.S. Bancorp made a total $50 million in low-interest loans, of $5 million to $10 million each, to seven CDFIs focused on minority- and women-owned businesses and those in low- and moderate-income areas.

One of those CDFIs was the Black Business Investment Fund in Orlando, Fla., which used a low-interest loan from Minneapolis-based U.S. Bancorp to fund PPP loans to a number of small businesses, including a security firm, an IT consultant and an early childhood education center.

More recently, U.S. Bancorp awarded the BBIF and over a dozen other Black-led CDFIs unrestricted grants between $50,000 and $100,000, for a total of $1.15 million. Those funds are part of

Carson said one reason U.S. Bancorp likes to work with the BBIF is that it can reach communities where the bank isn’t. The bank doesn’t have a commercial lending office or retail branches in Orlando, he said. It also doesn’t have the kind of relationships the nonprofit has with local African and Caribbean immigrant communities.

U.S. Bancorp may receive some consideration under the Community Reinvestment Act for making these kinds of investments, but Carson said that isn’t the primary reason for working with CDFIs. He also noted that some of them, including the BBIF, are outside of the bank’s CRA assessment area.

Closer to home, the company outlined the details of a $15 million fund to help small-business owners, particularly Black business owners, to rebuild after civil unrest in its hometown in Minneapolis. That fund includes $2 million in unrestricted grants to CDFIs and nonprofits in three specific, minority-majority areas of Minneapolis and St. Louis, where U.S. Bancorp Community Development Corp. is located.

Another benefit to working with CDFIs, bankers say, is that they can make much smaller business loans than a bank can, and exercise a little more flexibility in underwriting.

The Community Reinvestment Fund USA, for example, has developed an online marketplace, dubbed Connect2Capital, where underserved small-business owner can look for a responsible source of capital, usually from another CDFI.

“I would say that in general most of these businesses are looking for capital in the ranges of $25,000 to $50,000. These are smaller-dollar loans,” said Keith Rachey, the fund’s chief impact officer. “That being said, we offer everything from a $500 loan to a $4 million loan.”

Second-guessing the approach

Access to capital and resources was an issue for minority business owners well before the pandemic, but COVID-19 has hit them especially hard.

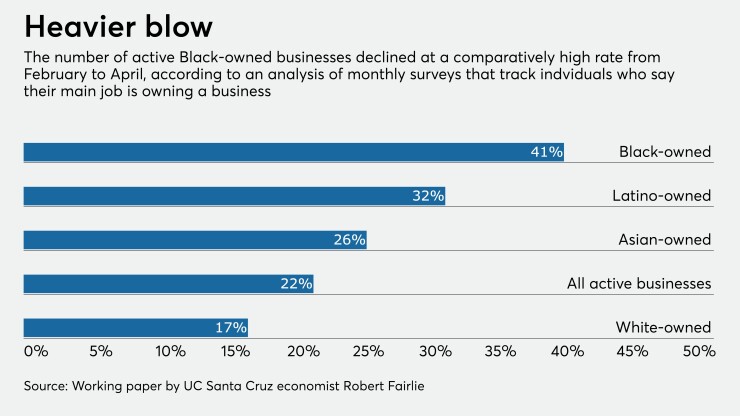

A recent study by Robert Fairlie, a University of California, Santa Cruz economist, found that the number of active Black-owned businesses plunged by 41% between February and April, while the analogous declines were 32% for Latino-owned businesses and 17% for white-owned businesses. The overall number of active businesses, which was calculated using survey data from individuals who reported owning a business as their main job, fell by 22%.

While any small-business owner is going to face hurdles, Black entrepreneurs have some broader social factors working against them. They are less likely to have amassed generational wealth or home equity to tap for startup capital. Or they may run up against overt or unconscious bias when applying for a loan with a bank. That all adds up to less capital to tap for upfront costs, less cushion to weather a crisis and less trust in mainstream financial institutions.

But some say that focusing too much on entrepreneurship ignores more significant factors contributing to the wealth gap and overlooks the way that white Americans have actually accumulated assets.

Chuck Collins, director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute of Policy Studies, questioned the assumption that business ownership is necessarily the most effective way to create multigenerational wealth.

Collins, who has studied the racial wealth divide extensively, said that mortgage subsidies and proactive private lending policies largely helped to accelerate white wealth accumulation after World War II. Because white Americans have historically had more opportunities to build home equity and generational wealth, they’re likelier to receive loans and gifts from friends or family for startup costs, or to tap their home equity for working capital.

In other words, business ownership and entrepreneurship are easier to achieve when a would-be entrepreneur has other assets to use as a cushion, so more focus should be on helping Black Americans to accumulate those first.

“If our goal is to close the racial wealth divide and boost assets, small business is sort of a secondary way to do that,” Collins said. “A lot of white wealth was not built from small business. It was built from having a decent job with a pension and access to homeownership.”

Community advocates acknowledge that entrepreneurship is just one of many necessary fixes — but an important one because of the multiplier effect it can have. When business owners can scale up, they can employ other people. For marginalized people who often get passed over for jobs and promotions in predominantly white workplaces, that’s crucial.

“By owning a business and owning and growing your own business, you’re not only providing your own individual wealth, you’re also hiring and multiplying within that particular community,” said Tiffany Bussey, founding director of the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

Helping those businesses to grow and providing an ecosystem in which they can thrive also creates a talent pool for the business community more broadly.

“As you start to provide a path to greater minority business ownership you also provide a path to greater diversity when it comes to boards and leadership positions at different companies,” said Kala Gibson, an executive vice president and head of business banking at Fifth Third Bancorp in Cincinnati. “You’re creating future leaders by growing minority entrepreneurship.”

Maintaining momentum

Meanwhile, but there is also an open question as to whether large companies, after the big splash of multimillion-dollar commitments, will stay involved in troubled communities over the long haul.

Malia Lazu, the chief experience and culture officer at Berkshire Hills Bancorp in Boston, whose background is in the nonprofit and community organizing worlds, said such funds “can be game-changing” for nonprofits operating on razor-thin budgets.

“When nonprofits know that there’s capital behind them, they can make bigger plans, and I think it’s always good when nonprofits can do quality work and can make bigger plans,” she said.

Banks can have a more lasting impact if they direct some of those dollars towards programs that help Black-owned businesses grow and eventually employ more people, Bussey said.

“There is an increased focus," Carson said, "because of George Floyd’s death and because of many other issues that are being highlighted by the pandemic: racial disparities in health care, in jobs, in living conditions, in many, many areas of society.”

He drew a parallel between Floyd and the death in 2014 of Michael Brown in St. Louis.

“I hope that it doesn’t take tragic events like this in every major metro area to continue this type of momentum,” he said. “I think the country is paying attention, but only time will tell.”