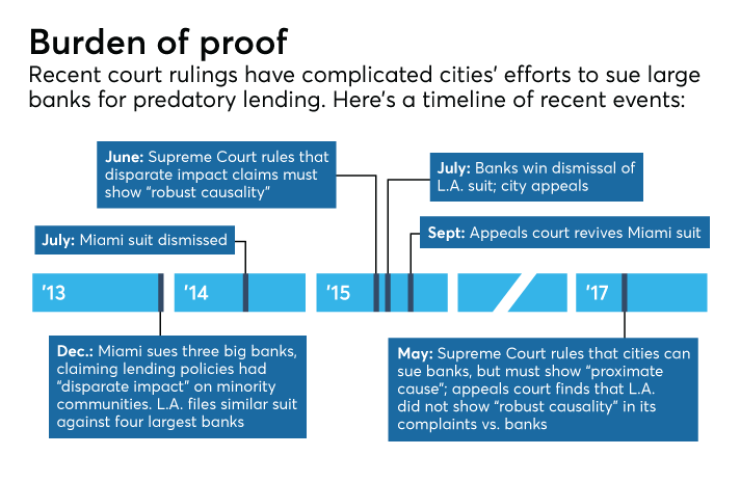

Two recent court decisions may be complicating cities’ efforts to sue banks for predatory lending.

While the courts have affirmed cities' right to file such suits, they are also holding them to a higher standard in proving that banks knowingly steered minority borrowers into high-cost home loans.

In a decision handed down May 1, the Supreme Court sided with a lower court in ruling that the city of Miami could sue Bank of America and Wells Fargo under the Fair Housing Act. The banks had argued that individuals could sue under that law, but cities could not.

The decision was generally seen as bolstering cities’ claims against big banks and, indeed, just two weeks later the city of Philadelphia filed a predatory lending suit against Wells Fargo.

Yet the Supreme Court ruling was seen by some as a victory for banks, since it also states that cities would have to show a much closer relationship between lending policies they claim are harmful and the actual harm done to the community.

Plaintiffs were dealt an even bigger blow on May 26 when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals handed down a ruling in the City of Los Angeles’ case against Wells Fargo and Bank of America. In affirming a lower court's opinion siding with the banks, the federal appeals court ruled that the city failed to show a robust link between the banks’ lending practices and damage to minority communities.

Taken together, the two rulings could make it more difficult for municipalities to prevail in lawsuits in which they allege that banks knowingly pushed high-cost, high-risk loans on minority borrowers, a practice sometimes referred to as reverse redlining.

“From a big-picture perspective, it’s very hard for cities or municipalities to handle that burden when it shifts to them, showing that causality between the policy or procedure at the bank and any disparate impact they’re alleging,” said Craig Nazzaro, an attorney at Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz. “If it’s not on the bank itself, it becomes a very difficult task for the plaintiff to overcome.”

For a policy or practice to have a disparate impact, it must affect members of a protected class more than others, even though it’s neutral on its face, as opposed to disparate treatment, in which the discrimination is intentional.

In its complaint, the city of Los Angeles said that three particular policies had had a disparate impact on the city’s minority borrowers: a compensation scheme that rewarded loan officers for higher-dollar loans; marketing targeting low-income and minority borrowers; and a failure to adequately monitor loans for disparities.

A lower court found the city’s argument lacking, particularly when it was limited to the two-year statute of limitations imposed by the Fair Housing Act. Ultimately, the Ninth Circuit agreed: that the city did not establish the “robust causality” it needed to make its case.

That need for robust causality has its origins in a 2015 case, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, in which the Supreme Court ruled that disparate impact claims are allowed under the Fair Housing Act. The court also said that plaintiffs must show a robust causal link between the policy and the disparate impact; evidence of racial disparity is not enough on its own.

Adding to cities’ challenges, the latest Supreme Court ruling says that cities will have to prove a much tighter connection, or proximate cause, between those lending policies they cite as harmful and the losses they’ve suffered in declining property values, lost tax revenue and increased spending on emergency services.

Suits filed against big banks by Oakland, Miami Gardens, and Cook County, Ill., were stayed when the Supreme Court took up the question of whether Miami had the standing to sue under the Fair Housing Act. Now that the court has answered that question, those cities are all expected to file amended complaints and argue their cases again. That includes the city of Miami, as the Supreme Court did not consider the legitimacy of its claim and remanded that back to a lower court.

The city of Philadelphia was the latest to bring a claim under the Fair Housing Act. On May 15, it filed a suit against Wells Fargo in which it alleged that the bank intentionally steered many minority borrowers into high-cost or high-risk home loans between 2004 and 2014. The city declined to comment for this article, but in a news release announcing the suit, city officials said that the May 1 Supreme Court ruling “re-affirmed the important role of cities in combating housing discrimination within our communities.”

Similar to other complaints, the Philadelphia suit is seeking compensation for lost property tax revenue resulting from unpaid taxes on abandoned properties, as well as declines in tax collections resulting from the declining value of foreclosed properties.

“We disagree with the claims that have been made in these suits. We don’t think we engaged in the conduct alleged and it doesn’t reflect how we’ve approached lending in any of those communities or in any community across the country,” said Tom Goyda, a spokesman for Wells Fargo. “We’re going to continue to focus on homeownership in all the communities where we do business.”

Stuart Rossman, the director of litigation at the National Consumer Law Center, said that cities are unlikely to back down from filing suits against banks, but he acknowledged that the recent rulings by the Supreme Court and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals will force them to retool their approach.

“The question is what kind of case is going to be successful? Part of this is trial and error,” he said. “We’re going to have to go back to the drawing board and look at what happened with the city of L.A. and see if we can come up with a better mousetrap.”

Courtney Statfeld Tippett, a principal at McKool Smith, said she views the Los Angeles ruling in particular not as deterrent, but as guidance for how cities could pursue claims more successfully. She said, for example, that cities would be wise to bring in ex-employees of banks they are suing to help corroborate claims that banks intentionally pushed minorities into higher-cost loans.

“If they have good lawyers, they’ll take the guidance the courts are giving them for how to pursue these claims,” she said.

Still, these recent developments could also bolster the defenses of lenders charged with discriminating against minorities. For the last decade or so, financial institutions accused of predatory lending have often chosen to settle out of court in an effort to minimize publicity, said Joseph Lynyak, a partner at Dorsey.

“Now you’ve got a much more favorable ruling,” he said. “I think you’re going to see people who can show they did nothing wrong say, ‘We’re going to fight this because we’ve got this defense of robust causation.’ ”