WASHINGTON — President Trump is expected to sign a memorandum Friday asking for a review of Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. powers to unwind a failing large bank, becoming the latest torchbearer in a yearslong effort by the GOP to revamp the controversial provision of the Dodd-Frank Act.

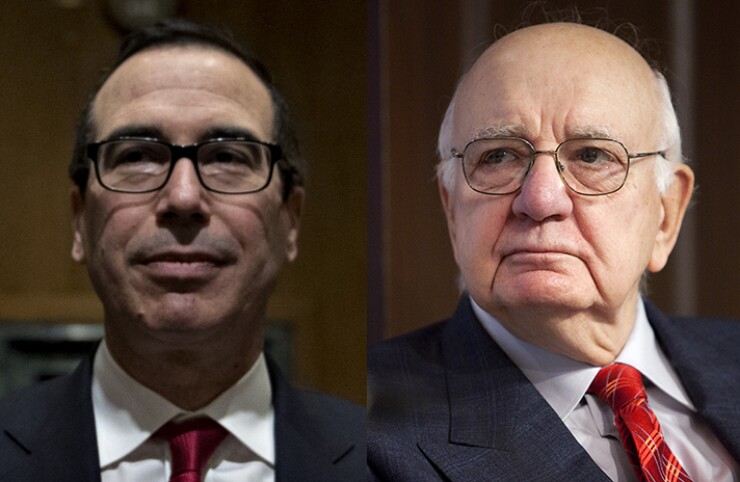

Yet the president and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, who is tasked with carrying out the review, are courting significant risks in targeting the authority, including the complexity in replacing it and fears it could heighten — rather than diminish — concerns about “too big to fail.”

Earlier this week, Mnuchin argued that the FDIC’s orderly liquidation authority could lead to perceptions that a bank is “too big to fail.” But in remarks on Friday to reporters, he acknowledged that eliminating those powers would have to go hand in hand with bankruptcy reform.

“The bankruptcy code right now doesn’t work — so if entities were to go through bankruptcy, I think it is important that we have necessary changes to the bankruptcy code," he said.

But crafting a bankruptcy reform that is capable of unwinding a large bank without sparking a market panic, like the one seen in 2008 when Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, is easier said than done.

Supporters of the FDIC’s orderly liquidation authority — who have included such prominent figures as former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers — argue that no amount of bankruptcy reform will work. Indeed, they see it as making “too big to fail” worse.

“The bankruptcy code is a fabulous insolvency framework, but it works most effectively for companies that have stable asset values, and are not dependent on continuous access to the financial markets,” said Michael Krimminger, a former general counsel at the FDIC who has testified to Congress in defense of orderly liquidation authority. “If the only available process for large financial companies is the bankruptcy code, you increase the possibility of a bailout in the future.”

Is OLA a bailout?

Republican arguments that OLA, found in Title II of Dodd-Frank, constitutes a bailout turn on the fact that the FDIC has the ability to draw liquidity from a special Treasury fund to handle the failure. Though it’s far from clear that the FDIC would need to use that draw, GOP policymakers argue that its existence puts taxpayers at risk. The president's memo asks Treasury to specifically determine if OLA poses such a risk.

"President Trump is absolutely committed to make sure that taxpayers are not at risk for government bailouts of entities that are 'too big to fail,' " Mnuchin said Friday.

There are also doubts among Republicans about whether the FDIC would fire senior management and wipe out certain creditors, as the agency has envisioned. Instead, they claim the agency would be picking winners and losers.

In a speech this week, former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker disputed that idea.

“Under the experienced auspices of the FDIC, managements would be removed, viable operations could be sold, stockholders and unsecured creditors would lose,” he said. “Under the provisions of OLA, the failing institution will, by any reasonable definition of the word, have in fact failed — there is no ‘taxpayer bailout.’ ”

But Republicans, and even some senior FDIC officials, raised the prospect that Title II might create a moral hazard.

“If you rely on OLA, you are encouraging them to have too-low capital, because they know they're going to be bailed out,” said FDIC Vice Chairman Thomas Hoenig, who advocates raising capital levels on large banks in order to make their breakup through bankruptcy more feasible. “We should not require of our citizens, our taxpayers, to be the backstop of the financial industry.”

Others, including Volcker, disagree. They note that any cost to the Treasury would be ultimately reimbursed by imposing assessments on large financial institutions with more than $50 billion of assets.

“OLA has an industry self-policing aspect to it that bankruptcy doesn’t have,” said James Wigand, the former head of the FDIC’s Office of Complex Financial Institutions, which oversees the resolution of large banks. “In the event a firm fails, and the liquidity financing takes a loss, the failed firm’s peers have to pick up the tab. By law, it’s never the taxpayers.”

Is bankruptcy reform a viable solution?

Even if OLA has problems, it’s unclear whether bankruptcy can be reformed in order to accommodate large financial institutions that are in the midst of a crisis.

Several bills in the House and Senate have taken different forms and focused on different aspects of reforming bankruptcy — including measures to protect against the fire sale of assets by counterparties, to ensure that the bankruptcy proceeds fast enough to prevent market panic, and to designate bankruptcy judges qualified to deal with large financial institutions. Republicans even managed to pass a bankruptcy reform bill in the House last year — and again this month — but it has not been taken up by the Senate.

In an ironic twist, some Republican have suggested taking their cues from the FDIC’s OLA in devising bankruptcy reform.

A bill currently making its way through the House, for instance, proposes to amend Title 11 of the bankruptcy code to establish a framework for the creation of a clean bridge company that would allow parts of the firm to operate while its assets are liquidated. That is very similar to how the FDIC has envisioned a potential large failure under its single-point-of-entry strategy, which would involve the establishment of a bridge bank to hold still-operating subsidiaries while the former parent is expunged.

“The way they want to fix the bankruptcy code, you'd be doing everything you're trying to do in OLA, in bankruptcy,” said Paul Kupiec, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a former FDIC official.

Given the FDIC’s long experience in resolving banks, some Republicans seem to believe replicating the agency’s strategy could bolster the viability of bankruptcy reform.

“The single-point-of-entry strategy was largely conceived in the process of writing the OLA rules,” said a Republican aide, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “We're not taking that benefit or feature out of the environment entirely. We're just moving it from OLA to bankruptcy.”

But proponents of keeping OLA in place argue that the bankruptcy process has a number of limitations, starting with the question of liquidity.

“The U.S. government, by definition, has the deepest pockets of any provider of liquidity that could assist in a wind-down or reorganization of a failed company,” Wigand said.

Even leading proponents of reforming bankruptcy to handle large bank failures — like University of Rochester professor Thomas Jackson and Davis Polk partner Randall D. Guynn — have acknowledged there needs to be some framework for government-funded liquidity.

Moreover, there is the significant problem of how a bankruptcy would be coordinated with international regulators. The FDIC has been working since the passage of Dodd-Frank to strike agreements with its foreign counterparts to ensure a large bank failure could be handled without creating problems in other territories.

It’s not clear that any bankruptcy reform can achieve that end.

“It is the absence of the resolution framework that might inexorably lead some future government to rescue big failing financial institutions, just as happened in 2008,” Volcker said. “What needs to be understood is that the existing approach has been developed in concert with other leading international regulatory authorities. This is an area where a common methodology is critically important internationally. After all, the banking institutions potentially involved invariably are themselves international in scope.”

Wigand noted, also, that OLA gives U.S. regulators legitimacy in the eyes of their counterparts abroad.

“It is through an OLA process that the host jurisdiction knows what the likely outcomes will be because of having discussions with the U.S. agencies in advance,” Wigand said.

If the U.S. bows out of OLA — which it has encouraged several foreign financial regulators to adopt — then banks could be forced to beef up their capital levels abroad.

“In effect, the U.S. would be abandoning the international standards,” Krimminger said. “My fear is that U.S. financial companies in Europe would likely see additional capital and liquidity standards imposed on them by European regulators.”

This argument does not necessarily carry much water with critics of the current financial regulatory landscape, however.

“Capital is a strength, not a weakness,” Hoenig said. With higher capital levels, “You’re going to have stronger institutions.”

Can OLA be eliminated by the current Congress?

The president’s memo is seen as an indication it will seek a legislative fix, though Mnuchin did not commit the administration to doing so. He promised to listen to all sides of the debate first before making any recommendations.

"We are going to do the review” of Dodd-Frank “and do what makes sense," Mnuchin said. "We are listening to regulators' views, we are listening to people in the previous administration, we are listening to people who were impacted by this and will be taking that into account.”

Some Republicans, meanwhile, are toying with the idea of eliminating the FDIC’s new powers before figuring out what should replace them. Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., has argued that the Senate could use the budget reconciliation process, which requires only a majority vote,to eliminate OLA. Title II has been evaluated by the Congressional Budget Office to cost $15.2 billion over a 10-year period, making it an eligible target to reap budget benefits if it is scrapped.

“The only way you can do that is probably through the reconciliation process,” said the Republican aide.

If Republicans succeeded in eliminating the FDIC’s powers, that could theoretically force Democrats to the bargaining table, making it easier to pass bankruptcy reform.

“If we succeed, then I think we have all the momentum we need to pass the Chapter 14 provision,” said the aide, referring to the additional section of the bankruptcy code that could be created to accommodate large financial institutions.

It’s not clear that Democrats would go along with a plan. They could balk at changing bankruptcy, and the financial system would remain at risk.

“In the event it is repealed without an enacted reform to the bankruptcy code, we'd all better cross our fingers,” said Karen Shaw Petrou, a managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics. “OLA is slow-mo bankruptcy. It doesn’t save the company — it allows the government to step in and basically snatch order from potential chaos.”

Ian McKendry contributed to this article.