Just how unattractive do deposits have to get before they quit growing?

Without offering customers much by way of incentives or interest, banks continued to amass deposits in the fourth quarter — at an average clip of 8% versus the third quarter, based on results from 40 of the largest U.S. banking companies tracked by KBW Inc.'s Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

No one expects that kind of growth to continue forever. But there is little to suggest that banks can't continue to defy the basic principles of price elasticity for at least a little while longer.

Customer gripes about low interest rates on checking and savings accounts are taking a backseat to broader economic concerns and demographic trends that have put a focus on accumulating savings and minimizing risks. And even when those trends play themselves out, stronger banks will be able to keep the deposit train rolling by making acquisitions, luring customers away from rivals and exploiting the other benefits of the flight to quality that's already underway.

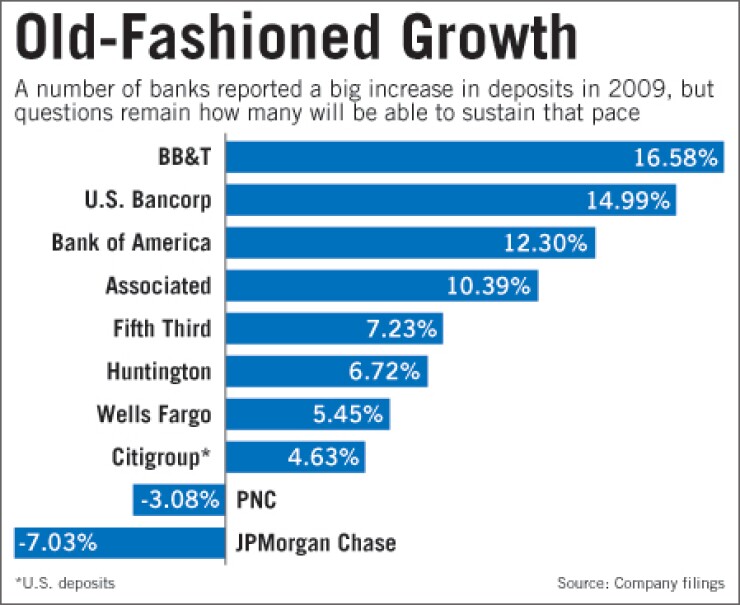

"People are saving more, and on a relative basis, I think banks are getting more of those savings," said Andrew Cecere, chief financial officer of U.S. Bancorp in Minneapolis, which posted a 15% increase in deposits from the end of 2008 to the end of 2009. And while financial pressures certainly have forced some consumers to drain their accounts, "the net of it," Cecere said, "is that we have more customers and have taken share during this downturn."

In the aftermath of an overdose on leverage, the United States has become a nation of dutiful savers. Personal savings as a percentage of disposable income has recovered from a low of 0.8% in April 2005 to a rate of 4.7% in November, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. And capital preservation will become an even bigger priority for baby boomers, as they age.

All of those savings have to go somewhere, and banks are well positioned for the windfall — even if they are only offering to pay around 20 basis points on an interest-bearing checking account.

"For short-term savings, deposits are a safe haven and the preferred vehicle for most people," said Gordon Karels, banking professor and finance department chair at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "A lot of it stems from the uncertainty with respect to the equity market and other investments."

Despite last year's rally in equities, stocks have yet to regain the level of confidence they once enjoyed. Stock funds showed outflows of $7.1 billion in October and $2.8 billion in November, according to the Investment Company Institute, a trade group that tracks changes in fund flows. The jittery markets of recent weeks suggest that crisis-weary investors are still feeling rattled in 2010.

Bond funds, meanwhile, look less compelling to investors in the wake of concerns about the potential impact of rising interest rates. Inflows to bond funds slowed from $44.9 billion in October to $36.2 billion in November, ICI data show.

The concurrent surge in bank deposits has been especially valuable to the industry as it tries to recalibrate its funding profile to become less reliant on debt.

"Our strong deposit growth and muted asset trends have created a lot of liquidity, and we've reduced wholesale funding by $17.5 billion on a year-over-year basis," Kevin Kabat, chairman and chief executive of Fifth Third Bancorp, told analysts last week. Transaction deposits at the Cincinnati company rose 6% from the previous quarter, Kabat said, with $1.1 billion of growth in demand deposit account balances and $1.5 billion of growth in interest checking.

Productive deposit gathering also should help banks lessen the impact of the Obama administration's proposed "financial crisis responsibility fee," which would subtract government-insured deposits from the covered liabilities on which the 15 basis-point tax would be based.

Not all big banks boosted deposits in 2009. Some, such as JPMorgan Chase & Co. and PNC Financial Services Group Inc., intentionally allowed higher-cost deposits inherited via acquisitions to run off during the year.

But most banks were eager to grow deposits, even if the depressed lending environment did not necessitate that they do so.

"Once could argue, 'Let's not bring in any more deposits because we're not making any money on them, but then you look at the liquidity issue," said Terry Moore, managing director of the North America banking practice at consulting firm Accenture. "The more deposits you bring in, the more liquidity you have and the more comfortable you feel about your ability to make it through the economic storm."

But deposit growth will have to cool off for banks to see a pickup in lending — the real sign that the storm is over. Customers "are keeping their liquidity and they've got it in deposits," Comerica Inc. Chairman and CEO Ralph Babb said last week. "They will spend that before they draw down on their [credit] lines."