-

In what would be its largest acquisition in more 15 years, UnionBanCal Corp. in San Francisco is buying Pacific Capital Corp. in Santa Barbara, Calif., for about $1.5 billion in cash.

March 12 -

Private equity fixed Pacific Capital and has agreed to sell it to UnionBanCal for a healthy price in a slow M&A market. There could have been more deals like this had regulators embraced PE.

March 12

Banks could learn a thing or two from the Treasury Department about owning up to problem assets.

No, government is not often touted in banking circles as a model for the private sector.

But there is a clear lesson in what the Treasury stands to gain from Pacific Capital Bancorp's deal to sell itself to UnionBanCal Corp.: swallowing a bitter pill early can prevent a lot of pain later.

UnionBanCal, a subsidiary of Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ,

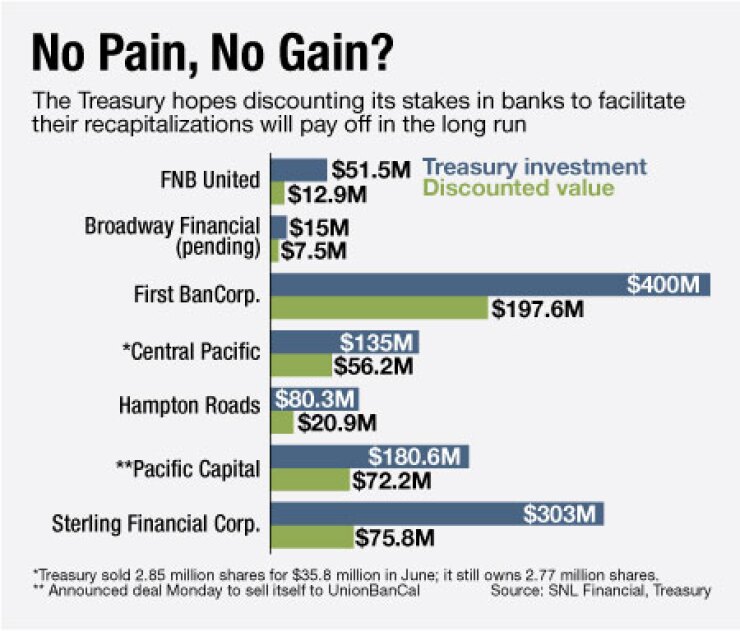

That would be roughly 90 cents on the dollar of the bailout money it invested in Pacific Capital through the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Granted, that would be a loss. The Treasury invested $180 million in Pacific Capital in 2008 — but things could have turned out a lot worse.

The Treasury agreed in 2010 to take its stake in preferred shares and convert to common equity at a 63% discount as a condition of a $500 million recapitalization led by the private-equity firm Ford Financial Fund LP. That firm is set to make $1.2 billion on the deal.

The rationale was that Pacific Capital, in Santa Barbara, Calif., needed capital to deal with a deluge of problem assets. Without the additional equity, its bank unit could have failed, rendering the Treasury's investment worthless as has happened in more than a dozen cases to date. The Treasury

"The ability to recoup an investment that is stressed at its face value is extremely difficult. If the bank goes into receivership, the Treasury is looking at pennies — and that might be generous," said Robert Klingler, a partner at Bryan Cave LLP who has closely followed Tarp. "So the Treasury has shown a willingness to strike a deal that makes it more likely for the company to either find new capital or someone willing to acquire it."

In that regard the Treasury stands out among the government agencies. While others have been

Christopher J. Zinski, a partner at Schiff Hardin LLP in Chicago, said the Treasury accepted the discounts likely because it figured it would do well alongside investors who expect high returns.

"The Treasury has first-class advisors helping them, and I think they have been selective and financially astute in structuring these deals," Zinski said. "They had to have taken notice of the success rate of the private-equity investor who is there to make money. I've got to believe this was part of their modeling."

The Treasury has agreed to the discounts on recapitalizations and acquisitions also in an attempt to prevent more wipeouts. As of January,

"Taxpayers are still owed $132.9 billion in Tarp funds, and taxpayers will never get back some of these funds," the report says. "Treasury has already written off or realized losses of $12 billion and Treasury predicts losses on other Tarp investments."

The Treasury declined to comment for this story.

Acknowledging that Ford Financial would profit handsomely, Carl Webb, president and chief executive of Pacific Capital and senior principal of Ford Financial Fund LP, said he hopes the Treasury is pleased with its return, too. "It is a unique transaction for the Treasury to receive this much on a bank that was troubled. They had talked about exiting earlier and didn't quite get the price they wanted, and it is a good fortune that they waited."

Like any other common equity shareholder, the Treasury is free to sell its stock at its discretion. In June it sold about half of its common shares of Central Pacific Financial Corp. for $35.8 million.

It initially invested $135 million, but accepted $56.2 million of common equity in early 2011 to help the Honolulu-based company complete a recapitalization.

Webb said the Treasury discount was important to his firm's deal because of a hole in Pacific Capital's balance sheet. Ford was committed to invest its $500 million fund — the entirety of the money it raised to invest in troubled banks — but that would not have solved all Pacific Capital's problems nor left the bank with a leverage ratio of 9% and a total risk-based capital ratio of 12% as required by its primary regulator.

The Treasury conversion, along with a conversion of subordinated debt into common equity, generated an additional $140 million of capital.

Ford had planned to hold on to the company for a few more years, Webb said, but it got an unsolicited offer from UnionBanCal at a price it expected to hit "eventually."

"We figured it would be plus or minus a five-year investment, but it turned out to be much shorter," Webb said. "We felt the economics were compelling enough that we couldn't ignore it."

The Treasury's view of the sale is important because Ford Financial wants to do more like it, Webb said.

"We want to use this template for other troubled banks. There are an awful lot of Tarp recipient banks that have not been able to repay. They are stuck from problem asset and capital standpoint. All the banks that can payback Tarp have paid back Tarp," Webb said. "I do think it was a good outcome for Treasury and we hope that they would entertain something like that again."

Kip Weissman, a partner with Luse Gorman Pomerenk & Schick, is not so sure the deal can be replicated exactly. The idea makes sense and would help speed up the resolution of Tarp, but there are challenges. First, as the economy has improved,

"They want out of Tarp, but they don't want to be embarrassed by a headline that reads 'Taxpayers Take Bath, While Hedge Fund Makes a Billion,' " Weissman said. "Treasury will seek to structure the next deal so that taxpayer gets par so that headline won't be there."