-

Consumer advocacy groups are urging regulators to take a closer look at how alternative lenders are using the stockpiles of personal information they collect.

October 2 -

In several wide-ranging discussions at the Digital Banking Summit, speakers raised issues around protecting mobile apps including the question of when millennials will start to care about mobile app security.

June 11 -

Big data has the potential to help people save money, improve their lifestyles, treat existing ailments and prevent new ones. But it's up to the business sector to earn the trust of consumers and lawmakers.

June 3

Companies of all types are turning to social media — Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and beyond — as well as tracking cookies for clues about customers' behavior, identity, preferences, habits and "life events."

Banks are no exception. They're not inclined to talk about it, but some are experimenting with mapping customer data to social media sites like Twitter and Facebook so they can "listen" to their customers' conversations on these sites. And some use tracking cookies (which record a customer's website activity even after the customer has left the company's site and report them back to a company's database) to monitor online banking clients' website travels.

Yet banks, unlike the e-book sellers, real estate agents or retailers doing the same things, have a special mandate around privacy and security because they are trusted custodians of their customers' delicate and personal financial matters. Mining customers' social posts and website activity brings them into an ethical grey area.

"Can banks can do this? Probably yes, as long as people make some of that stuff public," said Joseph Turow, associate dean for graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg School for Communication. "The notion of using social media activities, blog posts, various life activity — all these things are par for the course for some retailers.

"Should they? I would think from an ethical standpoint, probably not," Turow said. "Because the fact is, most people have no clue — they don't understand about data mining, they don't understand profiling. As a consequence, they don't really understand if a bank is treating them in a certain way based on profiles they have no idea exist. It's not illegal, but it really does raise ethical implications."

One large bank used "fuzzy logic" technology based on IBM's Big Match software to map its entire customer information file against all Twitter users in North America, according to an executive involved in the project. The bank found that 5% to 7% of its clients are active Twitter users. It then did "social media listening" and decided that about 1% of what those customers shared on Twitter is relevant to the bank. To extract those useful nuggets, the bank identified 21 life events — such as marriage, birth of a child, new job, new house, and divorce — that could warrant a follow-up action or message from the bank. It built a list of keywords associated with those life events and set up a crawler and routing process so when tweets about those life events appear, they're pushed to marketing people, relationship advisors and call center agents.

Another bank wanted to know the last 10 things that have happened with each customer — in social media feeds and at the bank, the executive said. The bank and its vendor built a dashboard showing the customer's LinkedIn profile in one pane, their last 10 Tweets in a second, and their last 10 bank transactions in a third, to get what a 360-degree view of the person's life. The technologists made the dashboard available to all bank employees so they could do "analytics between their ears."

Customers do not opt in, nor do they know about this monitoring at either bank — the feeling is that anything shared on Twitter is public. "On Twitter, you're broadcasting your views to the world in general," said the executive.

Turow is skeptical about this rationale.

"I suppose that on a single variable activity, it would be very obvious to you that you got [a message or offer] because they found about this. Some people would find that a little creepy. I think the better thing to do would be to tell the person where you got that information.

"And if you can't 'fess up to it, you probably shouldn't do it," he said.

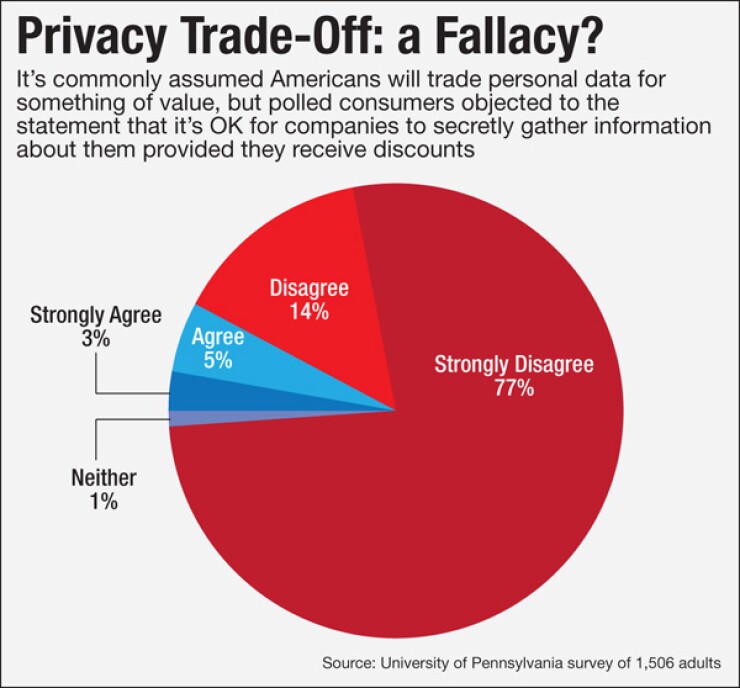

Several recent studies show Americans' attitudes toward privacy mirror Turow's. Although marketers commonly assume that people are willing to give up information in return for discounts, according to a University of Pennsylvania study, 91% of Americans say it's not fair for companies to collect information about them without their knowing, even for a discount. The study also found that although 84% of Americans want to have control over what marketers can learn about them online, 58% believe they have no control over what marketers can learn about them. A Pew Research study that came out last month found that 74% of Americans believe control over personal information is "very important," yet only 9% believe they have such control.

University of Pennsylvania researchers have concluded that a majority of Americans are resigned to giving up their data — that is why many appear to be engaging in the tradeoffs with which they philosophically disagree. Resignation occurs when a person believes an undesirable outcome is inevitable and feels powerless to stop it.

According to David Hoffman, a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers, the key to using tracking devices is letting customers opt in.

"Everyone has a different definition of what's intrusive," he noted. "We can do personalization based on behavior and analytics. But in the end, it should be opt-in, not pushed obtrusively in someone's face."

What about something most if not all banks do behind the scenes — analyze customers' transaction data?

"I would argue it depends on how that information is used," Hoffman said. "You could see that quickly becoming something that someone who is unscrupulous might take advantage of. It could be used in ways that you might consider unsavory."

For instance, one card company has boasted that it can predict when a couple will divorce based on their spending patterns. "On the other hand, there are patterns and predictive analytics around behavior that have positive connotation, such as marriage. I suspect that could be used for good."

Following Cookie Crumbs

A similar case is the use of tracking cookies. One example of a bank using cookies to observe customers' behavior after they leave its site is M&T Bank in Buffalo.

"You have to understand how the customer migrates from online to offline. There are a number of technologies you can use to follow customers from an online search to a mobile phone geolocated in a store," said Eric Lancaster, M&T's head of digital marketing and customer analytics technology, at SourceMedia's Banking Analytics Symposium this month in Boston.

The bank plants the cookies in onboarding emails to customers. "There are opportunities in the measuring space to get really sophisticated and granular," Lancaster said. "You then acknowledge where they've been and where they're going so you can create a whole journey map across channels and across lifecycles."

The question of intrusiveness comes up all the time, Lancaster said. "It's one we talk about with our legal partners," he said.

However, the bank doesn't have the "customer experience of creepiness of following you," he said. "A lot of the tracking we do is without personally identifiable information. It's all code and technology. When we paint that picture, it settles some folks down."

Amazon makes liberal use of tracking cookies, Lancaster pointed out. "I guarantee you whatever you look at [on Amazon], three or four websites later, you're going to see it again," he said. "So some of it is becoming instituted into the culture. It's something that has to be carefully monitored, but we haven't run into any issues with it."