-

The transformation of brick-and-mortar offices into high-tech sales centers has become an urgent matter as consumers increasingly transact through digital alternatives, yet branches still generate more sales than any other channel.

October 30 -

Many banks are aggressively closing branches to cut costs. Those banks must be mindful about branches in moderate- and low-income neighborhoods or risk downgrades after their next Community Reinvestment Act examination.

August 26 -

Everything is on the table including the table as banks accelerate their efforts to trim real estate costs. Options range from subleasing branches that are too large to finding professional investors who will buy the branches and lease back a portion of them.

October 8

Bank executives are doing their best to shut down low-performing branches that fail to pull their weight. Or are they?

A new study shows they may not be moving fast enough, something analysts have been

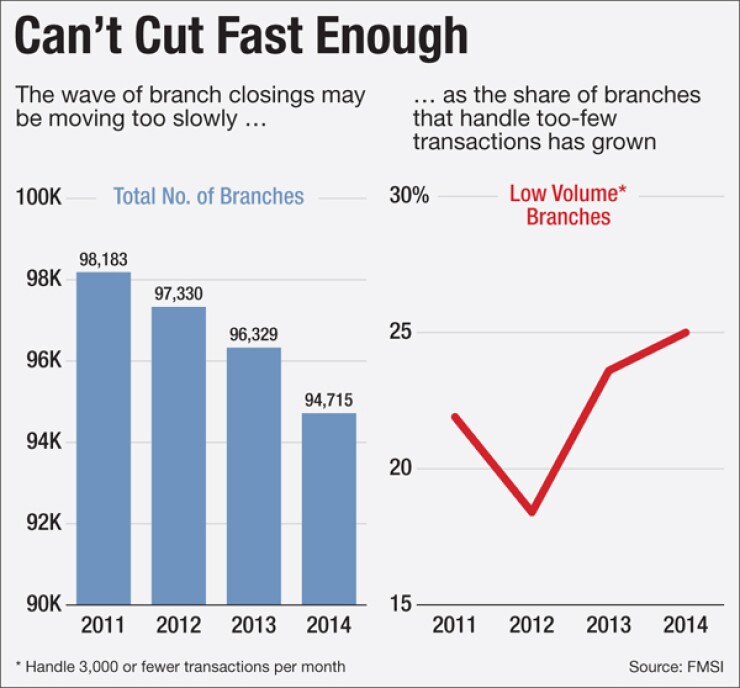

The number of U.S. branches has dropped steadily since 2009, when the total peaked at 99,540, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s latest Summary of Deposits report. Banks operated a total of 94,715 branches at June 30 of this year, a 5% decline from 2009.

The closures have come partly as a result of M&A deals, when banks

Technology is also driving the trend. In one recent example, the $3.3 billion-asset First Bancorp in Southern Pines, N.C., said in August it would

Yet another important measurement the number of underperforming branches is on the rise, according to a new study by FMSI, a banking-software firm in Alpharetta, Ga.

FMSI defines a branch as low volume if it processes no more than 3,000 transactions per month. The number of such branches, as a proportion of all branches, rose to 25% this year. That was up from 21.9% in 2011. FMSI obtains the data for its report through its customer contacts and limits the details that it makes available.

The upward spike occurred as the nationwide branch count has shrunk, because "even branches that once had heavy volume are now falling into the low-volume category," said Meredith Deen, chief operating officer at FMSI.

The situation is costing banks an arm and a leg, at a time when they can ill-afford any expense leakage. Banks should look at reducing the number of workers at a branch, cutting back on operating hours or closing underperforming branches, Deen said.

"Low volume branches can be very costly to operate," Deen said.

Shutting down a branch is easier said than done, said Mark Oldenberg, the chief financial officer at Citizens Community Bancorp in Eau Claire, Wis. The $570 million-asset company said last month that it will

"Nobody likes closing a branch," Oldenberg said. "Every branch that we looked at closing, we tried to find a way to keep it open. At some point, there was a realization it was going to take more resources than we had to make it successful."

It is often more difficult for a community bank to close branches, because of the emotional attachment the bank's employees and directors have to their communities, said Howard Bluver, the chief executive of the $1.8 billion-asset Suffolk Bancorp in Riverhead, N.Y.

"Many of my board members are intimately involved with their communities. It's where they live, where they work and own a business," he said.

"But as a board member, when you show them the analytics, if it's a mature board, they will say that it's too bad to close the branch, but it's the right thing to do," Bluver said. "When you do a thorough profitability analysis of the branch, it sort of jumps off the page, the decision you need to make."

Suffolk looked at transaction volume and several other factors in determining which of its branches to close, including deposits per branch and geographic proximity to another branch, Bluver said. The most important factor was a specific branch's level of profitability. Suffolk has

"When I first got here about three years ago, I found Suffolk was like a lot of community banks that are more than 100 years old," he said. "A relatively small percentage of our branches constituted a relatively larger percentage of our deposits."

Banks have taken varying approaches in how they tackle inefficient branches. FMSI, for example, sells software to help banks better manage tellers and working hours to save money. Suffolk's Bluver hired an individual banker, whom he knew from his time at the former Greenpoint Bank in Brooklyn, to examine Suffolk's branch network and suggest changes.

And then there is the example of really going all-in. The $22 billion-asset Webster Financial in Waterbury, Conn.,

"The JLL relationship has given us a lot more discipline around rationalizing our branch network," Jim Smith, Webster's chairman and CEO, said during an Apr. 17 conference call. JLL has helped Webster cut costs in downsizing or closing "corporate-type facilities" and retail branches, Smith said.

"You'll see more on the expense-reduction line as we go forward," Smith said.