There has been a

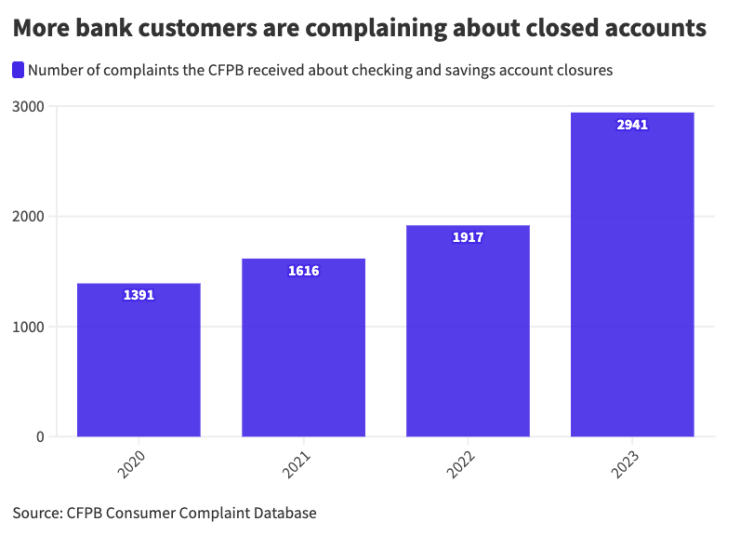

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau received 2,941 complaints about bank savings and checking account closures in 2023, about a 50% increase from 2022 and nearly double what it was in 2020. In addition, journalists at

Insiders chalk the increases up to a combination of aggressive AML rules, the automation of AML and the quest for efficiency and cost-cutting which leads to quicker investigations of suspicious transactions, if they are investigated at all. But a combination of advanced AI, richer customer data and more human involvement could help reduce the volume of closed accounts.

Representatives at large banks say that because they have millions of customers, the apparent large number of account closures is actually small, relatively speaking.

For instance, JPMorgan Chase has 80 million consumer customers and 6 million small-business customers, Managing Director Jerry Dubrowski pointed out.

"The percentage of instances where we would close an account for suspicious activity, when you use that as a denominator, is extremely low," he said. "When we make a mistake, we work to resolve it."

Large banks don't want to shut down customer accounts, Dubrowski noted.

"We want to build long-term relationships with our clients," he said. "That's the whole point of our business. The only time an account would be closed would be after an appropriate review and a consideration of the facts."

JPMorgan Chase has a human look at every case before deciding whether to close out an account, he said.

Dubrowski also noted that sometimes a legitimate customer is an unwitting victim of fraud or money laundering. "Nonetheless, that presents a threat to the bank and to the broader financial system. So if money is coming into his account from places that we know are not good places, we will close the account where we're required to."

The bank's goal is to build long-term relationships with customers, requiring a careful and thoughtful approach to account closures, Dubrowski said.

"That said, we are bound by the rules and regulations that all financial institutions have, and we have a compliance program in place as we are required to have," Dubrowski said. "And we act in accordance with that."

The bank uses algorithms to spot patterns that might be indicative of AML violations, "but then it has to be reviewed," he said. "We have well-trained professionals who look into this and examine this and then make decisions as a result of it." Every single potential closure gets reviewed by a human analyst, he said.

Experts say banks could be doing more to reduce account closures.

"It's an industrywide problem," said Marcia Tal, founder of Tal Solutions, who previously worked for 25 years at Citibank. "The law of large numbers means that even if it's a very small percentage, you can talk yourself into feeling good about that. But that's not the case when you're closing people's accounts and when there are individuals that matter that are your customers being impacted."

Artificial intelligence can help, experts say, but only with the help of rich data and more human involvement.

The problem of digital customer relationships

Once upon a time, before a bank closed a customer's account due to suspicious-looking activity, an employee who knew that customer, such as a branch manager, was consulted who could provide some explanation for activity that looked sketchy.

Banks lose more context on their customers every year, said Uri Rivner, CEO of Refine Intelligence.

"For centuries, banks were essentially a relationship business," he said. "You would walk into an office, you would talk to a banker and they would ask you questions. And these conversations were very useful to both sides, because the banker would know about you. It's not just 'know your customer' in the sense that they know your name and recognize you. They actually understood you, they understood your life story, they knew your family. And once you came in to do something, they would ask you about it, just out of curiosity, and offer personal financial advice."

Now that the majority of banking takes place on a smartphone, all this is gone.

"We have an app and we punch some keys and we say, 'OK, move $30,000, I want to deposit something,'" Rivner said. "All of this is happening without that interaction. And because of that, the banks actually lost a very important superpower that they used to have, which is really understanding all of those life stories."

This is becoming true of small businesses, too, as banks close branches and drive business clients to digital channels.

"That familiarity is deteriorating," Rivner said. "As a result, you have systems that generate a lot of alerts without the context, without anyone in the bank able to say, 'What do we know about this person?'"

Further, it's typically hard to reach customers with questions about their account activity. Branch managers may leave messages on customers' phones and not hear back for two weeks, Rivner pointed out.

And banks don't really have that kind of time. In some cases, the Federal Bureau of Investigation or another government agency tells banks to immediately close accounts due to criminal activity. "When we got the feed from the federal agencies, there wasn't much of a process — it was 'do it now,'" said a former AML executive at a large bank.

Some banks are starting to use digital inquiries, where they approach customers through digital channels with a request for information that takes the customer two minutes to complete, Rivner said.

"You ask some questions and the customer provides some information, and it's all very consistent and very structured," he said. "It provides the context that the AML team would need to resolve the case very quickly."

Such inquiries could also be used to educate customers who unwittingly break money-laundering rules. For instance, cash structuring is a practice of depositing large amounts, say $9,000 and then $5,000, in different places on the same day.

"Some people do it because they're criminals, but most people do it because they don't understand this is a federal offense," Rivner said. Banks are required to report such activity to the federal government and if they keep seeing it, they will rid themselves of the customer in order to de-risk.

But banks could send the customer a digital inquiry that explains what behavior they're observing and why that activity could be breaching federal regulations.

Of course, customers that are money launderers or criminals will try to come up with legitimate reasons for their behavior. But their transactions will eventually give them away, Rivner said.

"The key is to map life stories and to map the genuine activity that people do," he said.

Then AI models can look at alerts, look at past transactions for the account and do some analysis that can help differentiate between the customer who is paying tuition for their kids abroad from someone who is moving money for a drug operation.

"Once you understand good behavior, you can discard a lot of the noise and a lot of the false alarms and say, we're not going to close this account," Rivner said.

Better use of customer data

Another approach to getting better at understanding customers is to make better use of first-party data, in which customers report what they are doing, Tal said.

Tal has built a platform called PositivityTech that's intended to be the voice of consumers. "By reading and listening to what is going on, which is what I spent my career doing even when I was at Citi, I realized that there are ways to work around this situation," she said.

By understanding and analyzing customer data, a bank could start to understand why customers do the suspicious-seeming things they do. Operational efficiencies could come out of these reviews, as well as better outcomes for customers and fewer complaints to regulators such as the CFPB, Tal said.

This would require bank executives to prioritize this type of work, Tal said.

"That's where the leadership has to say, 'We are not going to close accounts that we shouldn't be closing. We have spent a lot of money in the past to keep them open,'" she said. "The last thing you want to do is close them. There's a large cost to that."

Tal also recommends that developers creating AML models visit customer-facing environments and listen to customers.

"If you're building a model, you have to create a contextual reference for why you would choose one variable versus another variable," Tal said. "What data would you bring in? Do you understand how this would impact consumers or corporate clients? … The more you interact with the way the business actually works, understand the processes and understand the dynamics, the better the models will be and the more integrated things will be."

But there always needs to be some type of human override process to anti-money-laundering software before it shuts down accounts, she said.

How AI might help

Banks use anti-money-laundering and fraud-detection software to find suspicious activity, which is typically overseen by a centralized group of people who are removed from customers. AML software tends to generate high volumes of alerts.

AI, in theory at least, can take the millions of red flags generated by AML and fraud systems and help to refine them by quickly analyzing historical customer data that can shed light on what a customer was really up to when they completed a certain transaction. But there are several complications and challenges to this.

For any model to work, be it rules-based or AI-based, it needs rich data and a feedback loop, Rivner noted. In fraud detection, for instance, bank analysts can get data on the type of device and the customer's typical behavior with the device — the way they move a mouse or hold a smartphone, for instance — that helps them understand whether fraud might be involved.

"Once you have rich signals, you can then move that through a sophisticated AI system, because you have a lot of context," Rivner said. And when fraud occurs, customers usually report it quickly because they want their money back, so the system can get the feedback it needs to learn to discern true fraud from false flags.

"But when you think about AML, all you know is someone deposited $10,000 in cash, you know where the branch is, but that's it," Rivner said. "So you are lacking a lot of context, and you are operating on the thinnest layer of data, and you don't have any feedback that you can use."

Bank customers' complaints of sudden account closures track a rise in automated anti-money-laundering decisions and possibly outdated AML rules.

When banks file suspicious activity reports to the government, they don't learn whether those transactions were part of criminal activity or not. And customers that have money laundering happening on their accounts are typically complicit or unaware; either way, they're not reporting it.

"Even if an AML system is correct, you don't know that it is correct," Rivner said. "And if it was wrong, you don't have any feedback to say, hey, this was actually a false decision. The reality is it's very, very difficult to get accurate results, even if you use the most sophisticated AI, because of those two facts: thin data and lack of feedback."

Some banks deploy systems that try to understand whether they see an anomaly in the customer behavior, Rivner said.

"Most anomalies are generated by perfectly legitimate life stories," Rivner said. "For example, buying a house, selling a house, buying a car, doing a big construction project, starting a cash intensive job, doing construction or landscaping, getting a loan. These sort of things are happening at a certain point to almost everyone. But transaction-monitoring systems will see it as a red flag because it is anomalous. This is the root cause of why you see so many mistakes or false alarms."

One thing AI can do is analyze time frames, according to Kieran Thompson, head of product for fraud at ComplyAdvantage.

"If we are seeing transactions for a merchant acquirer where one of their merchants is a barbershop or a restaurant and they're processing transactions at 3 a.m., now there might be a use case where that is a genuine transaction, but more likely that's actually either money laundering or fraud," Thompson said.

Large language models can look at a payment reference and the characteristics of the payment.

"If someone is putting a payment reference for rent or utilities and the amount is two dollars, that discrepancy can be picked up: that's not actually going to be a rent payment because it's too low," he said. "And vice versa, if you have an Uber payment or a Lyft payment for a taxi service and the payment is multiple hundreds of dollars, we can also pick up on that as well."

AI can also detect signs of money-mule activity, for instance, and organized crime groups that have 10 or 20 accounts and are moving funds between accounts they already own to obfuscate those funds.