Kailyn McComb was convinced at an early age that she would never work at her family’s bank.

She was wrong.

Her attitude started to change earlier this year following an internship with the Community Bankers Association of Ohio. That experience helped show her the role bankers play in helping others meet big goals such as owning a home or starting a business.

“It changed my outlook from banking is boring to banking is a community service,” said the 21-year-old college senior. “When you break it down, banking is not only helping people obtain their financial needs but also achieving their dreams.”

As she finishes her last semester at Ohio State University, McComb, a strategic communications major, is set to become a social media coordinator and universal bank trainee at Heartland Bank. The McComb family is the largest shareholder in the $844 million-asset institution.

Family owned and operated institutions such as Heartland are welcoming the next generation, often millennials, into the fold as the industry struggles with succession planning and attracting younger employees.

“Millennials get a bad rap that they aren’t willing to work hard,” said Alan Kaplan, founder and CEO of the executive search firm Kaplan Partners. “But there are people in every generation that aren’t willing to work hard. Millennials as a generation are motivated, are generally bright and understand technology. But they want to know what the work means.”

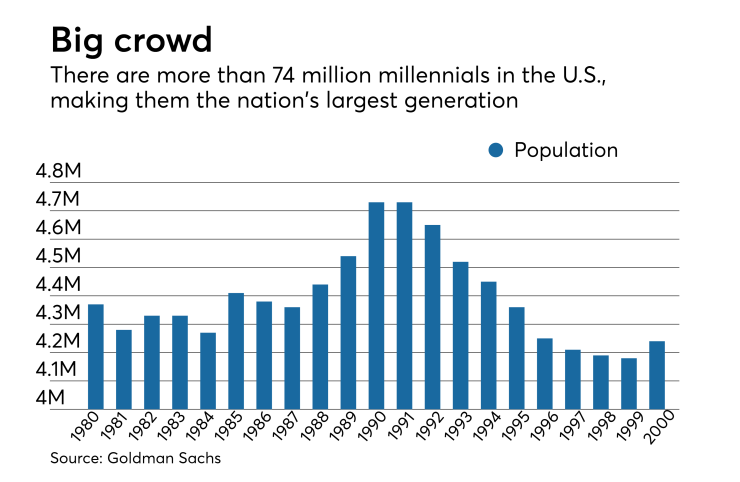

Millennials, loosely defined as individuals born from the early 1980s to early 2000s, are slated to become roughly half of the workforce by 2020. Depending on the range, there are anywhere from 75 million to 92 million millennials, surpassing baby boomers as the nation’s largest living generation.

That makes them an important, yet challenging, demographic for banks to recruit as clients and employees.

Succession woes are often cited by banks as a reason to sell. The number of U.S. banks has dropped by about 30% over the last decade, to about 5,100 at Dec. 31, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

A summer survey of about 600 community banks conducted by the Federal Reserve and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors found that a third of respondents flagged succession as an important or very important factor for considering a buyout offer.

Finding someone to take over can be particularly difficult for banks in rural or smaller markets, said Bob Wray, managing director at Capital Corp., a Prairie Village, Kan., firm that provides investment banking and consulting services to banks, including family owned institutions.

The problem goes beyond top posts. Banks may struggle finding qualified employees in areas such as lending and compliance.

“We have a lot of banks in towns in the Midwest that don’t have college-degree-type jobs,” Wray said. “If you have the capability and go away to college, even if you go back to the town, they can’t utilize that education.”

Arthur State Bank in Union, S.C., which has strong roots in some rural markets in the state, has expanded into more urban areas such as Spartanburg, Columbia and Rock Hill, in search of loan demand, said President and CEO Carlisle Oxner. The $488 million-asset bank can trace its origins back to the 1930s when Harry Arthur approached his father about opening a local institution because the area lacked a bank.

Oxner’s daughter, Ashleigh, recently became to fourth generation of her family to join the bank, starting on the anniversary of her father’s first day. She previously spent time living in Washington, where she did event planning for a lobbying firm and was a finance assistant for a political organization. After three years, she decided to return home.

The 25-year-old teller said she will “take it year by year” when asked whether she envisions eventually succeeding her father.

“I want to make my way through the different departments to find where I can be the most useful,” the younger Oxner said. “I didn’t want a job that I went to every day. I wanted a career.”

Carlisle Oxner said he worries about finding loan officers and tellers who are eager to stay at the bank long term and won’t be lured elsewhere by more money.

“I would love to see this bank continue to stay independent … but it’s not totally up to me or Ashleigh even,” he said. “It’s up to our shareholders.”

Bringing in the next generation can be one way — but not necessarily the best or only way — to recruit younger employees, said Adam Eckels, co-founder of AJ Consultants. Employees talk to friends about their jobs, so millennials may actually recruit others to their bank, added Eckels, who got into the executive search business because of a high school friend who was in the industry.

“I think one of the reasons banks have trouble attracting millennial talent is they themselves have trouble adapting to the new way of hiring,” Eckels said. “The millennial world is a new one and some banks aren’t willing to adapt to them or realize they are important.”

There are other ways that community banks improve how they attract a new generation of workers, industry experts said. One way is to cultivate a sense of purpose, said Joe Sullivan, president and CEO of Market Insights.

“Millennials are looking for a reason to join this family business,” Sullivan said. “What is my bank trying to do in this community?”

Scott McComb, Heartland’s president and CEO, has found attracting millennials to be essential to the bank, which is based in a Columbus, Ohio, suburb. The area’s labor market is tight (it had 3.5% unemployment in April) and numerous universities provide a young and educated talent pool of recruits.

Heartland makes the work environment inviting by having a more relaxed dress code and hosting fun activities such as tailgating at Ohio State football games. Banks need to make plans now to recruit people who will be at the institution a decade down the road, he said.

The elder McComb, who is excited his daughter joined the bank, made clear that their relationship doesn’t guarantee that she will be in line to someday become CEO.

“Most banks blame selling on the burden of regulation, but that’s not really true,” Scott McComb said. “They don’t plan for succession and they hang on past their usable years.”