-

Three investment banking giants are reportedly planning to jointly build a data management company.

August 20 -

FIS and merger partner SunGard, along with all other vendors in the space, have not been able to come to market with innovative core systems or software platforms that adequately address the new digital paradigm banks face.

August 18 -

Executives at more than half of banks fear they lack a comprehensive handle on technology and operations risks and would welcome software that enables them to tackle the problem, a Deloitte survey shows.

July 29

A little-discussed problem has plagued the financial services industry for decades: a high percentage of trades break down perhaps as many as 30% to 45%.

Each processing glitch means someone in a back office has to analyze the details of the trade, figure out what went wrong and repair it. Often, the problem is a data hiccup a securities identifier code or a company identifier is not recognized by the receiving firm's system, for instance, or a buy-side firm is using a Bloomberg product code while the supply-side firm's using a code from IDC.

"The cost of repair is out of control," said an executive who spoke off the record and is involved with a utility JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley are building to fix this problem. "For every million dollars a firm spends on data management, there is an average of $3 million in trade repair costs."

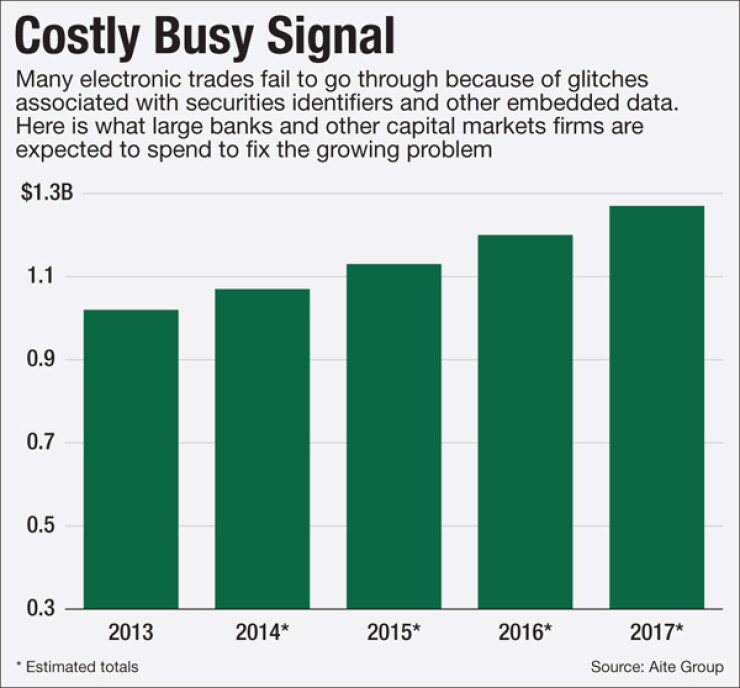

Capital markets firms will spend about $1.2 billion next year on reconciliation technology and services, including external and internal investment, according to Aite Group.

The new bank-run utility, called SPReD (for Securities Product Reference Data), will use a combination of people and technology to build a clean, accurate securities reference data file and use it to fix trade errors. It will start with equities and certain types of derivatives.

"All the banks including us have all these different data streams being collected around the bank," noted an executive at one of the participating banks. "We're all receiving this data independently, bringing it into the company, and we have teams of people purchasing the data. For all this reference data, if we're all using the same data anyway, [the question is] can we get it to a place where it's scrubbed and clean, a golden copy."

Most large banks are trying to do this in a more automated fashion, said Virginie O'Shea, senior analyst at Aite Group.

Securities reference data is data about the data in trades the securities identifiers like CUSIP or ISIN numbers, the financial instrument data (name, interest rate, issue date, currency, etc.), the counterparty identifiers. Making sure all this data is accurate can sound trivial but is actually a huge challenge.

"People call reference data static data and it's really not," O'Shea pointed out. "Look at any of the standards they've tried to impose in various areas the industry doesn't tend to follow those standards."

There are several standards for securities identifiers, including CUSIP (which stands for Committee on Uniform Security Identification Procedures), ISIN (International Securities Identification Number) and the Bloomberg Global Identifier, but because there are so many and because companies aren't required to use standards at all, this doesn't help.

"The industry pays lip service to standards and then doesn't actually do it," O'Shea said.

Trades often travel through a long chain of custodians and brokers on the way from the end client, such as a pension fund, to final settlement.

"They're all changing the data as they go along because they've got different systems," O'Shea said. "That's why you're doing so much reconciling to external parties internally. You can see why failures happen, because that data is getting slightly altered, according to the standards of each firm."

Some say that in the future, blockchain technology will be used to streamline the massively complicated securities processing world. Several startups, including Digital Asset Holdings, have been formed to create distributed ledgers for handling securities trades.

Another challenge is that within securities firms, end business units each want data delivered in a format they are used to and they are unwilling to agree on a uniform system, O'Shea said. "If you can't get reference data right at the enterprise level, how on earth are you going to do it across the industry?" she said.

In some cases, the difficulty is that software programs accept fields of different lengths a field limited to nine digits obviously cannot accept a 12-digit code.

"The data problem is quite endemic and not easily solved," O'Shea said. "I don't think anyone's anywhere near solving it, and it's not something you can change in a six-month project."

The banks are working with SmartStream, a vendor that provides reconciliation services and that already has a reference data utility. SmartStream's technology acquires data from data vendors (it will also bring in counterparty reference data from Clarient and Swift), processes each feed separately (this is called single-vendor cleansing), cross-references the instruments, adds missing attributes, identifies errors and mismatches, and fixes errors automatically when possible. Where errors cannot be automatically corrected, it sends exceptions to operators, and in the end, delivers the processed data to each client's security masters.

The banks hope the utility will provide them with returns in operational efficiency.

Why do this now?

Market volatility provides a reason to resolve trade issues quickly. There is also pressure from the Depository Trust and Clearing Corp. and others to shorten the trade settlement cycle, as Europe has already done.

A third reason is the ongoing need to get a better handle on risk. "People don't have a good handle on some of their reference data, and it's impacting their ability to make decisions," O'Shea said.

Attempts have been made in the past to create a reference data utility. They have failed as competing firms have been unable to agree on standards, formats and classifications. "It just falls apart politically every time," O'Shea said.

In the case of SPReD, getting large banks to agree on data quality benchmarks and policies is going to be tough, she said.

"I think it will be great if they manage it, but I think it will take them at least five years to get this off the ground," she said.

Another hurdle is that the project is not a profit maker and therefore unlikely to excite high-level executives.

"This is something nobody loves doing," pointed out David Weiss, senior analyst at Aite Group. "Very few people get up in the morning to say, 'I'm excited I'm going to create a cutting-edge security master we'll have the best security master ever.' That doesn't happen. This goes into the SWAD category, as in 'stuff we all do.'"

At some banks, this utility could be looked at as a way to "save a little money and fire half our people," Weiss said. "You don't have a managing director saying, 'Let's do this great new system.' It's not a profit center."