When community advocates ask banks to provide accounts for the estimated 63 million people in the U.S. who are unbanked, bankers typically raised two concerns.

One is that this population is unsophisticated and will soak up expensive branch and call center resources.

The other is that these customers will use banks like check cashers and drain their money out every month — a losing proposition for the banks.

Both arguments appear to be shot down by a new trove of data collected from four of the largest banks: Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, U.S. Bank and Wells Fargo.

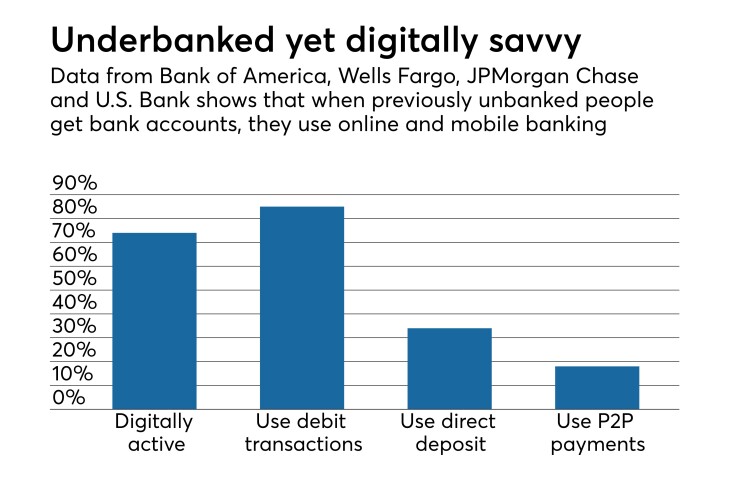

Seventy-four percent of the 3 million previously unbanked people who opened accounts at the four banks in the past year are digitally active. In fact, they are heavy users of online and mobile banking. They are statistically no more likely to call or walk into a branch than existing bank customers.

Basically, their banking behavior is no different from anyone else’s.

“We’re seeing people use these accounts the way the rest of us use them — we’re charging things at the counter, buying things online, depositing our checks,” said Jonathan Mintz, president and CEO of the Cities for Financial Empowerment Fund, a funding and advocacy group that has been the driving force behind the data project as well as an effort to bring the underbanked into the financial mainstream called Bank On.

“That kind of robust usage is an important story we have not been able to tell before,” said Mintz, who is a former commissioner of the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs.

Jason Martin, checking and debit product executive at Bank of America, which offers its Safe Balance account to the previously unbanked, said he was pleased to see the high number of digitally active users.

“It’s largely on par with the rest of the checking portfolio,” he said. “That number didn’t surprise me very much because it’s what clients want, it’s what’s convenient for them. That’s our goal, to make our services convenient to customers so they can bank the way they want to bank.”

Asked if the accounts are profitable, Martin said the bank takes a long-term view.

"We look at relationships, not at individual product profitability," he said. “We believe that over time these customers will grow in their relationship with us. They’ll remember that Bank of America was the one that helped them out, gave them their first account, and educated them on that checking account.”

The results

All told, 3 million accounts were opened under the Bank On initiative, and about 1.4 million remain. Some people have closed their accounts and left the banking system; others have opened new accounts within the same bank, Mintz said.

The banks reported a 25% closure rate on these accounts over the past year. This is in line with normal account closings.

"Some of those closures aren’t necessarily bad things, they are graduations," Martin said. "Banks need to make that transition process easier for clients so we can bring down that closure number.”

Seventy-two percent of the people who opened these accounts were new to the financial institution.

“That means the Bank On program is working, it’s bringing more clients into financial institutions, and that’s what we want to see because it helps them bank and manage their financial lives a lot easier,” Martin said. “It’s a number we want to continue to see grow.”

The rate of online-bill-pay use among the newly banked was low, in Martin’s view. In some cities, it's under 3%.

“That showed me that we need to make that experience better, so more clients will use bill pay,” he said. “And it tells me we need to do more to educate clients on the benefits of bill pay.”

The data platform is designed to be used by all 23 banks that have certified Bank On accounts. The plan is to report annually to see how the market evolves.

A big lift

Getting four large banks to cough up account data in a harmonious way is an accomplishment in and of itself.

For years, community groups loosely aligned with Bank On have pelted local banks with requests for account data, sometimes on a monthly basIs. The groups would ask, how many people did you bank this month? Or how many people did you newly bank this quarter?

“Banks don’t necessarily know," Mintz said. "They know who they’ve newly added to accounts, but they haven’t always known which accounts can be counted or whether those customers were previously unbanked.”

The banks would report on the accounts that feel like their most basic.

Sometimes banks were unable to produce the requested numbers. Other times, employees were uncomfortable with the idea of voluntarily giving data to a local nonprofit or government. All the banks worried about whether their data was comparable with what other banks were providing.

“All parties were frustrated,” Mintz said. “It was a big lift, it was sometimes a source of tension and it was generally dissatisfying.”

Before building a national data reporting platform, Mintz’s team created a definition of the kinds of accounts that can be counted under the Bank On umbrella: They have to cost the consumer less than $5 a month and have no overdraft fees or hidden fees. They have to meet mainstream banking needs including direct deposit, bill pay and point-of-purchase transactions.

The team then defined each of the data points they would collect. Figures that seem straightforward, like “average balance,” can be tabulated in different ways; the balance could be gathered at the beginning of the month or at the end of the month. It could be an average. The community groups and the four banks spent a lot of time hashing out these definitions.

The advocates also had to figure out what they could reasonably ask banks to provide.

“The banks don’t have to report any of this,” Mintz said. “So it was great that they were willing to work with us. We had to figure out what’s feasible, what’s helpful, and what we could learn about how these accounts are being used.”

The banks did not want to give their competitors their internal numbers. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis agreed to be an anonymous and trusted aggregator of the banks' data.

The data portal lets users see at the ZIP-code level what is happening in their communities, but only if at least three financial institutions reported in that ZIP code.

Despite the progress the CFE Fund project seems to show, there is still work to do to help the financially disenfranchised, said Jennifer Tescher, president and CEO of the Center for Financial Services Innovation.

“While recent data releases that tout the decreasing rate of unbanked consumers, low unemployment and an increase in consumer spending paint a rosy outlook, a deeper dig into the data reveals that today, only 28% of Americans can be considered financially healthy,” she said. “They are collectively saddled with $13 trillion total household debt, more than $1.5 trillion in student loan debt, and a deficit of up to $14 trillion in retirement savings. The daily systems that help people build wealth, resilience and pursue opportunities are more fragile than ever, with many Americans just one or two unexpected events away from a financial crisis."

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at