'The second way' to close the wealth gap

After homeownership, business ownership is the main path to prosperity. Here's what banks and government can do to stimulate small-business growth.

Jose Moreno is at work. He’s almost always at work.

Moreno, the owner of the Cubamex sandwich shop in San Jose, Calif., gets to his store early in the morning and can be found most days in his shop, working. Most holidays, too. He says he can’t remember the last time he celebrated his birthday.

“I'm always working,” Moreno said. “Some days — not every day, but some days — I will close at 12, 1 in the morning. People make fun of me — they look at me and say, ‘Do you have a watch or a clock?’ Because you go around the clock, you know?”

He says he got that work ethic from his father, who owned a small corner store. Moreno and his brothers would help out, stocking shelves, taking inventory, calculating sales, cleaning the aisles.

“When I was a kid, he told me, ‘Some people go to work and they only work eight hours. And they go home and they think they worked,’ ” Moreno said. “He said, ‘That’s just making a paycheck. That's not working. Our business is not a profession — our business is our life.’ ”

Moreno spent most of his career working in the restaurant and service industries, but he’d always aspired to own a business. So in 2016, he found an empty restaurant space in downtown San Jose and decided to take the plunge. He sunk his family’s savings into the business, and when that wasn’t enough, he approached a bank about a small-business loan.

“I went to the bank, and I asked for a loan, and they said, ‘You need collateral. We will not take a risk if you don't have collateral,’ ” Moreno said.

The collateral he had to offer was his home, so he took out a home equity line of credit. He didn’t like having that debt hanging over him, so he worked 12 and 16 hour days to pay that loan off early.

And then COVID struck. State and local authorities began instituting lockdown orders in March, meaning that much of the Silicon Valley workforce that he usually depended on dried up overnight. His business — his life — was at risk of going under.

“I'm in downtown San Jose. There was nobody,” Moreno said. “One day I only sold like one sandwich. And then the second day I sold, like, three.”

“Our business is not a profession — our business is our life.”

Moreno’s experience in the COVID pandemic is emblematic of many of the roughly 30 million small businesses in the United States — 22 million of which are individually operated, meaning the owner is the sole employee, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. There are few concrete numbers for how many of those businesses have permanently closed in the past year, but some early estimates have put the figure anywhere from 80,000 to 160,000. It will likely take years for the full extent of damage from the pandemic to be felt in the broader economy.

“Business ... it’s a lot of sacrifice, a lot of work, and a lot of headaches,” Moreno said. “And it goes back to the principles. You need to be prepared, and willing to do all those things.”

But the pandemic has shaken even the most prepared business owners, and nonwhite business owners have been hit especially hard. If the incoming Biden administration and the banking sector want the country to bounce back from this crisis, there will have to be a renewed focus on how we approach small-business credit in general, and how we foster nonwhite business creation in particular.

Jose Moreno, owner of the Cubamex sandwich shop in downtown San Jose, looks onto the street from his empty restaurant floor. “There was nobody,” Moreno said of San Jose’s foot traffic after the first lockdown order in March, 2020. “One day I only sold like one sandwich.”

Jose Moreno, owner of the Cubamex sandwich shop in downtown San Jose, looks onto the street from his empty restaurant floor. “There was nobody,” Moreno said of San Jose’s foot traffic after the first lockdown order in March, 2020. “One day I only sold like one sandwich.”

‘The second way’ to wealth

Politicians of all stripes appeal to the virtues of “small business” (variously defined) as a matter of course. In a two-year stretch between 2010 and 2012, the phrase appeared in the U.S. Congressional Record more than 10,000 times, according to a contemporary analysis from National Public Radio.

But while exhortations over the virtues of American entrepreneurship can be overdone, the role that small businesses will have in America’s economic recovery from the pandemic — particularly in communities of color — cannot.

As with most elements of the crisis, the virus has had a disproportionate impact on businesses owned by people of color. One working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, published in June, estimated that while the total number of “active” small-business owners fell by 22% between February and April, the figure for Latinx business owners was closer to 32%. For Black-owned businesses, there was a 41% drop in active owners.

These figures come in the context of a renewed public interest in racial disparities of all kinds. The protests that erupted all over the country last summer in the wake of the killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police opened up an earnest — and heated — public debate about the role of police and the appropriate use of force.

But it also turned popular attention to the yawning wealth gap between white and Black households in America, and the role that access to financial services plays in perpetuating that discrepancy. And the financial disadvantages that Black Americans, Indigenous peoples and other communities of color experience persist even though regulators have an array of legal instruments at their disposal specifically designed to close it.

Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, followed in 1974 by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and in 1977 by the Community Reinvestment Act, to say nothing of the many additions and revisions made to those authorities in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act and elsewhere. Those laws amount to a comprehensive reversal of the federal government’s policy toward racial exclusion, replacing explicitly restrictive and segregationist policies put into place in the New Deal era with explicitly inclusive ones.

Gwendy Donaker Brown, left, and Gilberto Soria Mendoza, part of the policy team at Accion Opportunity Fund, stand in an empty plaza in Oakland, Calif. Relatively small business loans made to low- and moderate-income entrepreneurs — like those the Fund provides — can have outsized impacts on communities, they say.

Gwendy Donaker Brown, left, and Gilberto Soria Mendoza, part of the policy team at Accion Opportunity Fund, stand in an empty plaza in Oakland, Calif. Relatively small business loans made to low- and moderate-income entrepreneurs — like those the Fund provides — can have outsized impacts on communities, they say.

Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, followed in 1974 by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and in 1977 by the Community Reinvestment Act, to say nothing of the many additions and revisions made to those authorities in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act and elsewhere. Those laws amount to a comprehensive reversal of the federal government’s policy toward racial exclusion, replacing explicitly restrictive and segregationist policies put into place in the New Deal era with explicitly inclusive ones.

“There are a lot of tools out there that are about preventing discrimination, encouraging equal access to credit, and creating fair and affordable housing,” said Graham Steele, director of the Corporations and Society Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. “And a lot of the tools still exist.”

But after several decades of those tools and frameworks being in place, disparity persists in both wealth and access to financial services between white and nonwhite Americans — a reality tied in no small way to the legacy of exclusionary federal policies in place from the 1930s through the 1970s that gave many white Americans a foothold in intergenerational wealth that Americans of color have not been able to replicate at scale.

“Intergenerational wealth gets passed down — or not,” said Jesse Van Tol, CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a network of consumer advocacy organizations. “People are running the same race, but some people are starting 100 yards behind the starting line because they're born into a low-wealth family. That's a consequence of historic discrimination, and until and unless you address that, you're always going to have different outcomes at the finish line.”

For decades, homeownership has been touted by policymakers as the one of the surest paths to accumulating and passing on wealth in America. But increasingly, analysts say that more attention should be paid to the promises of small business, and the enormous impact a successful one can have on a family’s fortunes and trajectory across generations.

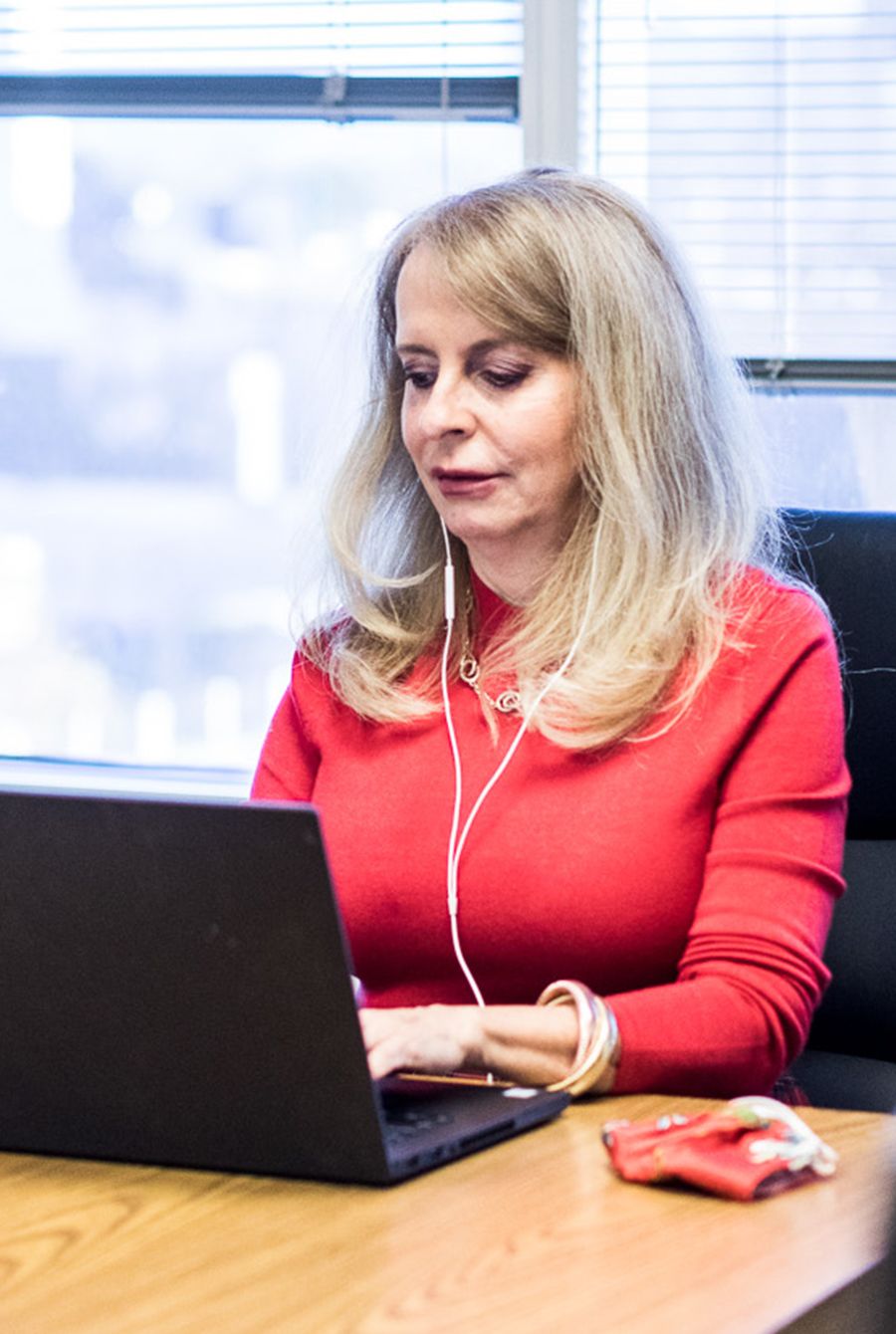

Luz Urrutia, CEO of Accion Opportunity Fund, working in the organization’s San Jose headquarters. Accion Opportunity Fund, a Community Development Financial Institution and nonprofit lender, focuses on providing small business loans to low- and moderate-income applicants.

Luz Urrutia, CEO of Accion Opportunity Fund, working in the organization’s San Jose headquarters. Accion Opportunity Fund, a Community Development Financial Institution and nonprofit lender, focuses on providing small business loans to low- and moderate-income applicants.

“Historically, we've talked about homeownership as the number one path to building wealth. Well, I think that small business has been the second way to build wealth,” said Luz Urrutia, CEO of Accion Opportunity Fund, a California-based community development financial institution and community advocacy organization. “We need to focus more resources on rebuilding minority small businesses. Because that is going to help put people back to work and eliminate the systemic racism that we all know is there.”

“We need to focus more resources on rebuilding minority small businesses. Because that is going to help put people back to work and eliminate the systemic racism that we all know is there.”

The post-pandemic years could be a turning point for the fortunes of millions of Americans, many of whom have long been left behind by the mainstream financial system. The direction of that turn may be decided in large part by the path the Biden administration and other state and local authorities chart toward recovery, and analysts say the cultivation of small business cannot be overlooked in that effort over the months ahead.

“Underserved small businesses — primarily Black, Latinx, Asians and women-owned, who already face significant challenges accessing responsible capital — will have an even bigger struggle to access capital to help them weather the storm that is COVID-19,” Urrutia said. “With that landscape, the intervention needs to be severe.”

Small businesses are vital to every local economy — by some estimates, employers with fewer than 500 workers employ nearly half of all Americans. But they are even more important in communities that have found themselves lacking access to financial services or even basic employment opportunities over the span of generations.

Gwendy Donaker Brown, head of research and policy at Accion Opportunity Fund. Brown said many of the Fund’s clients can't obtain small business loans through traditional means because of their immigration status, language barriers or racial bias.

Gwendy Donaker Brown, head of research and policy at Accion Opportunity Fund. Brown said many of the Fund’s clients can't obtain small business loans through traditional means because of their immigration status, language barriers or racial bias.

“Particularly for the small businesses and owners that Accion Opportunity Fund serves, many of them face barriers to formal employment, to working for someone else, whether those be related to immigration status, language or more broad systemic racism,” said Gwendy Donaker Brown, head of research and policy at Accion Opportunity Fund. “That’s why so many individuals need to become entrepreneurs in the first place — because they do face barriers to gainful employment elsewhere.”

But just as the need for small-business lending has gone up, banks have drifted away from small-business financing over the past decade. In the years since the 2008 financial crisis, small-business lending by the banking industry has stagnated: According to an analysis by Rebel A. Cole, a professor at Florida Atlantic University, banks’ small-business portfolios for loans below $1 million shrunk by 6% between 2007 and 2019. Commercial lending, by comparison, more than doubled in the same period.

“Something that's really important for the incoming administration to understand is just how much the landscape has changed, certainly since COVID, but also since the Obama administration and certainly since the beginning of it,” Brown said. “We’ve had a dramatic pullback of banks in the small-business finance sector.”

There are many reasons behind that shift, but one of the fundamental ones is simple difficulty and cost: Small-business lending is expensive, and the risks are hard to quantify.

“The complexities of small-business owners themselves are significant,” Brown said. “They're unsecured loans, whereas with something like a mortgage, it’s really clear what you're getting. Even a student loan or even a payday loan — it's pretty clear what the parameters are.”

But those challenges can’t overshadow the value that a small-business loan can bring to a fledgling enterprise, and what a difference such opportunities can make for the communities that need them the most.

“Something that's really important for the incoming administration to understand is just how much the landscape has changed. We’ve had a dramatic pullback of banks in the small-business finance sector.”

One of the key differences between small-business lending in a historically affluent population versus a historically poor one is that richer entrepreneurs are more likely to be able to bypass the small-business loan market altogether by drawing on “friends and family” capital. Poorer prospective business owners are less likely to have that option, Brown said.

“If they're an immigrant who doesn't have friends and family capital to start or expand their business, it looks like a lender, taking a chance — or, in other words, assessing them effectively in such a way that they actually can provide that friends and family capital, if you will — to help them buy their piece of equipment to land that contract, to purchase that inventory around a specific holiday or time of year, to move ahead,” Brown said.

“Advancing racial equity in small business is not the silver bullet to undoing white supremacy and systemic racism in our society,” Brown said. “And it's a really important tool for advancing both economic equity and racial equity.”

A movie theater in San Jose, Calif. stands empty after state and local orders have closed many non-essential businesses. Closures like this one have put a considerable strain on thousands of small businesses all over the country.

A movie theater in San Jose, Calif. stands empty after state and local orders have closed many non-essential businesses. Closures like this one have put a considerable strain on thousands of small businesses all over the country.

Sticks and carrots

Urrutia says that as the Biden administration mulls its path forward in the months to come, one crucial policy change that will be needed is greater incentives for banks to do the kind of lending small businesses are most likely to benefit from. “The government has carrots and sticks, and there's no better time to use them than now,” she said.

One of the more pointed sticks that bank regulators have at their disposal is the Community Reinvestment Act. The anti-redlining law requires banks to lend to all parts of the areas where they have bank branches, including low- and middle-income borrowers in low- and middle-income neighborhoods, and evaluates banks for their loan activity in disadvantaged areas, including small-business lending.

Lenders and community groups have contended for years that the CRA’s longtime framework is ineffective, albeit for different reasons. Many in the industry have argued CRA exams are too subjective, and banks don’t get enough credit for investments that benefit the communities they serve but that are not covered by the law.

But community leaders and consumer advocates say the law as implemented has not been effective in generating investment in communities that need it the most, particularly communities of color. “Even pre-reform, CRA wasn’t strong enough,” Brown said. “If it actually had teeth and more transparency, some of the things that advocates have been arguing for years, I think perhaps that would also play a role” in helping shore up small business.

“There are a lot of tools out there that are about preventing discrimination, encouraging equal access to credit, and creating fair and affordable housing. And a lot of the tools still exist.”

One of the ways that could manifest, policy analysts say, is a fuller recognition of small-business lending in banks’ CRA scores. “Ultimately, CRA is a bit agnostic,” Brown said. “You can get credit for mortgage lending, [or] you can get credit for small-business lending. And so therefore I think a lot of institutions have chosen to meet their anemic CRA obligations in other ways,” namely in sectors of lending that doesn’t require as much expense or effort as small business.

Former Comptroller of the Currency Joseph Otting began a process of overhauling the CRA in 2019 — the first substantial overhaul since the early 1990s. But community groups said the resulting policy — finalized by acting Comptroller Brian Brooks in May — would incentivize banks to invest in a smaller number of big-ticket investments rather than a larger number of smaller loans that could spark small businesses and help disadvantaged neighborhoods build wealth.

Adam Briones, director of economic equity at the Greenlining Institute, said the clear first step for the Biden team is to reverse course on the Trump administration’s proposals and final regulations.

“The Trump administration has been very straightforward in their belief that regulation is something they would like to roll back,” said Briones. “From the perspective of the access to capital, consumer protection, an explicit focus on underserved communities who have been victims of discrimination, redlining, I think they’ve done an extremely poor job.”

While it is essential to revisit the regulatory “sticks” in CRA, Urrutia said, regulators should find ways to offer meaningful carrots to banks to make the kinds of investments that can make the biggest difference.

“Our public sector is more than just regulation,” Urrutia said. “It's about getting those organizations that play by the rules the opportunity and the freedom to do more.”

“Critical to that effort is the recognition of the costs of small-business lending. Under the Paycheck Protection Program, for instance, the government paid out a flat 5% fee for loans below $350,000 to banks who helped direct emergency loans toward businesses in need. But because some costs of underwriting loans are the same regardless of loan size, banks have a natural profit motive to write fewer bigger loans than many smaller ones.

But Van Tol of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition said the data coming out of the Paycheck Protection Program shows that some banks found a way to make those smaller loans.

“With PPP, you got this objective lesson — it's the same pricing, same credit risk. And yet some are doing much smaller loans and others are not,” Van Tol said. “It really shows you that banks could do it if they wanted to.”

Those incentives could be better developed in a future iteration of the Paycheck Protection Program or through other emergency measures pursued under the Biden administration that focus specifically on relief and recovery, but many banks are already thinking about how to help small businesses — particularly minority-owned businesses — get access to capital in the wake of the pandemic.

Mary Mack, head of consumer and small-business lending at Wells Fargo, said in an interview with American Banker in September that the bank was taking all the fees it has earned through implementing the Paycheck program and creating a capital pool for community development financial institutions to leverage into new small-business loans over the next several years.

“We know, for instance, that businesses owned by Black and Brown entrepreneurs are failing at twice the rate of white-owned businesses,” Mack said. “And how do we lean, particularly, into diverse businesses to help them with recovery?

“We don’t know who’s providing capital to who, at what cost — how small businesses, women-owned businesses, minority-owned small businesses, are receiving capital. That’s really important.”

“To learn how to operate in this environment — a lot of our customers have had to retool their own shops to be able to operate in a safe environment for employees and customers,” Mack said. “So how do we help with that, how do we help with funds going into CDFIs for business recovery and creation, how do we help with nonprofits leaning into the educational realm around these businesses? All of that is a structured program that goes back into the small-business community.”

Bank of America, which manages a small-business portfolio with more than 12 million clients totaling more than $20 billion of assets, also pledged $1 billion over four years to address racial inequality through a number of initiatives, including $200 million directed toward supporting minority-owned businesses, including clients and vendors.

“This is what we stand for,” Sharon Miller, head of small business at Bank of America, told American Banker in September. “We want to promote racial equality, and women’s equality. We want to be there for all clients we serve.”

Another untapped vein of regulatory potential lies inside the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and nascent rules implementing section 1071 of Dodd-Frank, which mandated the creation of a database for tracking discrimination in small-business lending.

The federal watchdog agency has dragged its feet for the better part of a decade on the endeavor, eventually resulting in a lawsuit and a court-supervised process requiring the bureau to make progress. The CFPB has said it is trying to reduce data collection burden for banks while grappling with the ambiguous definition of small-business lending in the statute.

In September, the agency signaled what the small-business database may eventually look like with a 77-page policy outline. But many analysts say the CFPB missed a crucial window from the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, when Black business owners had a much harder time securing Paycheck Protection Program funding than white-owned businesses. A database equipped to track loans by race and gender could have spotted such problems.

“If this was in place, community groups, small businesses and their advocates could have more thoughtful conversations with the largest lenders,” Briones said. “You can point out who’s doing well in the first place, evaluate where and how they’re making money versus where there’s a market for banks to consider growing.”

Gilberto Soria Mendoza, senior policy advocate for Accion Opportunity Fund. Mendoza said the small-business lending market lacks many of the guardrails and protections that other forms of lending enjoy, including basic data about lending activity and borrower protections.

Gilberto Soria Mendoza, senior policy advocate for Accion Opportunity Fund. Mendoza said the small-business lending market lacks many of the guardrails and protections that other forms of lending enjoy, including basic data about lending activity and borrower protections.

Gilberto Soria Mendoza, senior policy advocate for Accion Opportunity Fund, said lawmakers should set up stronger guardrails for small-business loans like there are for mortgage loans. The pandemic has made it clear how little is known about how these small businesses access capital.

“We know it has negatively impacted businesses; they’re shutting down all over the country,” Mendoza said. “But we don’t know who’s providing capital to who, at what cost — how small businesses, women-owned businesses, minority-owned small businesses, are receiving capital. That’s really important.”

Moreno, the sandwich shop owner, has been able to keep his business going through the pandemic in part because of an emergency relief grant he obtained through Accion Opportunity Fund. But he says business owners like himself will have to continue to find ways to get along without the benefit of banks.

“Banks don’t want to take a risk on losing money, at all,” Moreno said. “And they want to secure their investment, and besides securing their investment, they want to make profit off of it. I don’t know how we can overcome those two obstacles. I guess it’s been a challenge for many years. How can banks take a risk?”

Urrutia is more optimistic that the right incentives can be found to spur the kind of small-business investment that can bring wealth to communities of color. But only if everyone works together.

“I’m a firm believer that not one single sector of this economy can solve this problem alone,” Urrutia said. “So if you said to me, ‘Luz, the federal government can do it’ — no they can’t, not by themselves. ‘But Luz, what about the banks? You know, if they wanted to do it, they could do it.’ Nope, they can’t do it by themselves. Neither can philanthropists, neither can CDFIs, nonprofits.

“This has got to be a collaborative effort, because we all bring separate skills — and assets and tools and resources and value — that all are needed right now to help solve this problem.”

Photos by: Patrick Strattner